Dear Friends,

Distraction Series 13 brings us to November. In the United States in 2020, this month has started out with the stress of the election in addition to rising numbers of Covid-19 across the country. Madeline Gins’s book What the President Will Say and Do!! (1984) captures this feeling, and moment in time, quite well. In addition to the first essays, which seem eerily prescient of the current events, later in the book Gins brings us a particularly useful text for how to approach or try to maneuver through these times: “How to Breathe”. In order to help us move through November and to celebrate Madeline’s birthday on November 7th, we present a brief discussion of this text. We hope you are all taking good care and we wish you a safe and healthy November.

Yours in the reversible destiny mode,

Reversible Destiny Foundation and the ARAKAWA+GINS Tokyo Office

How to Breathe

by Amara Magloughlin

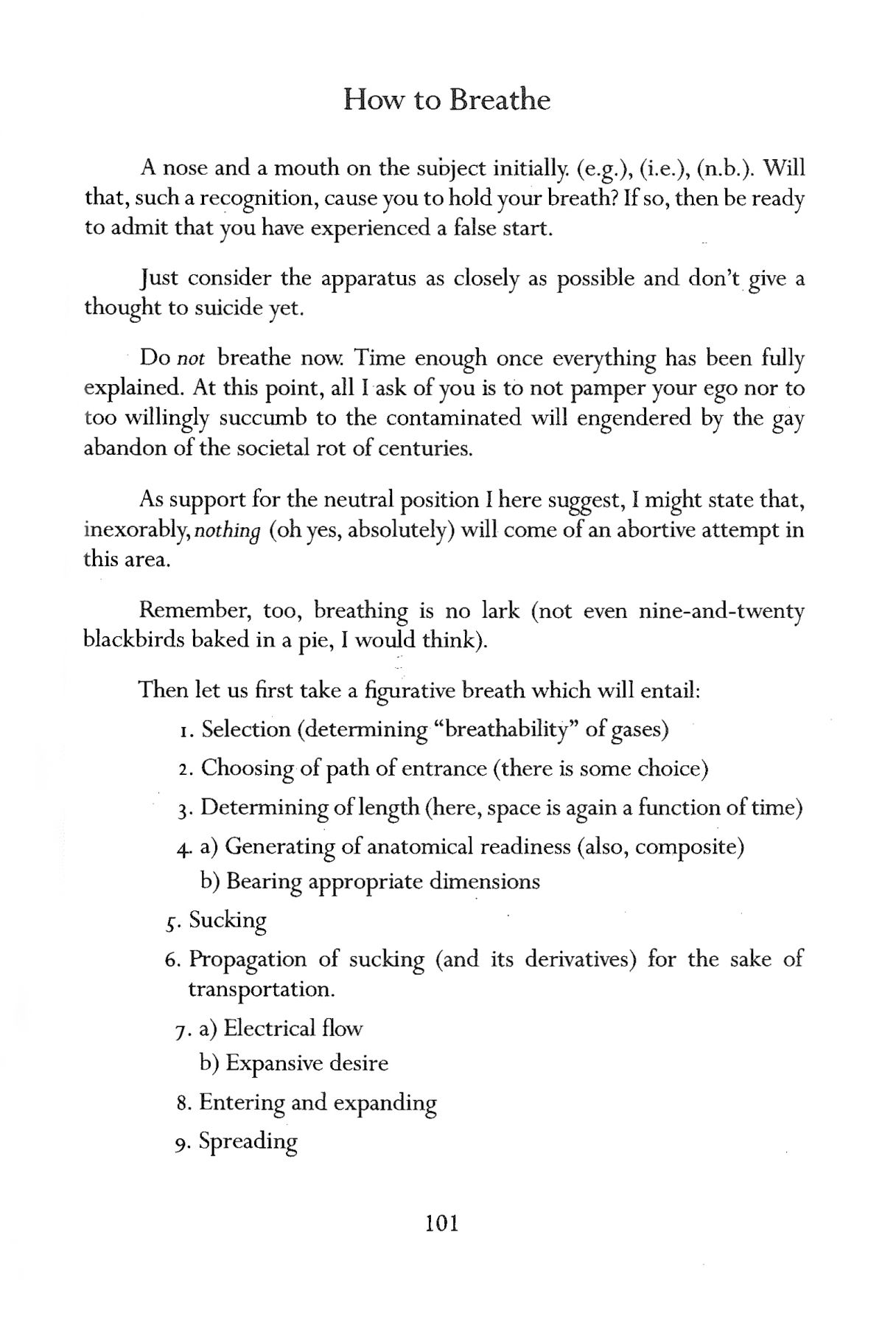

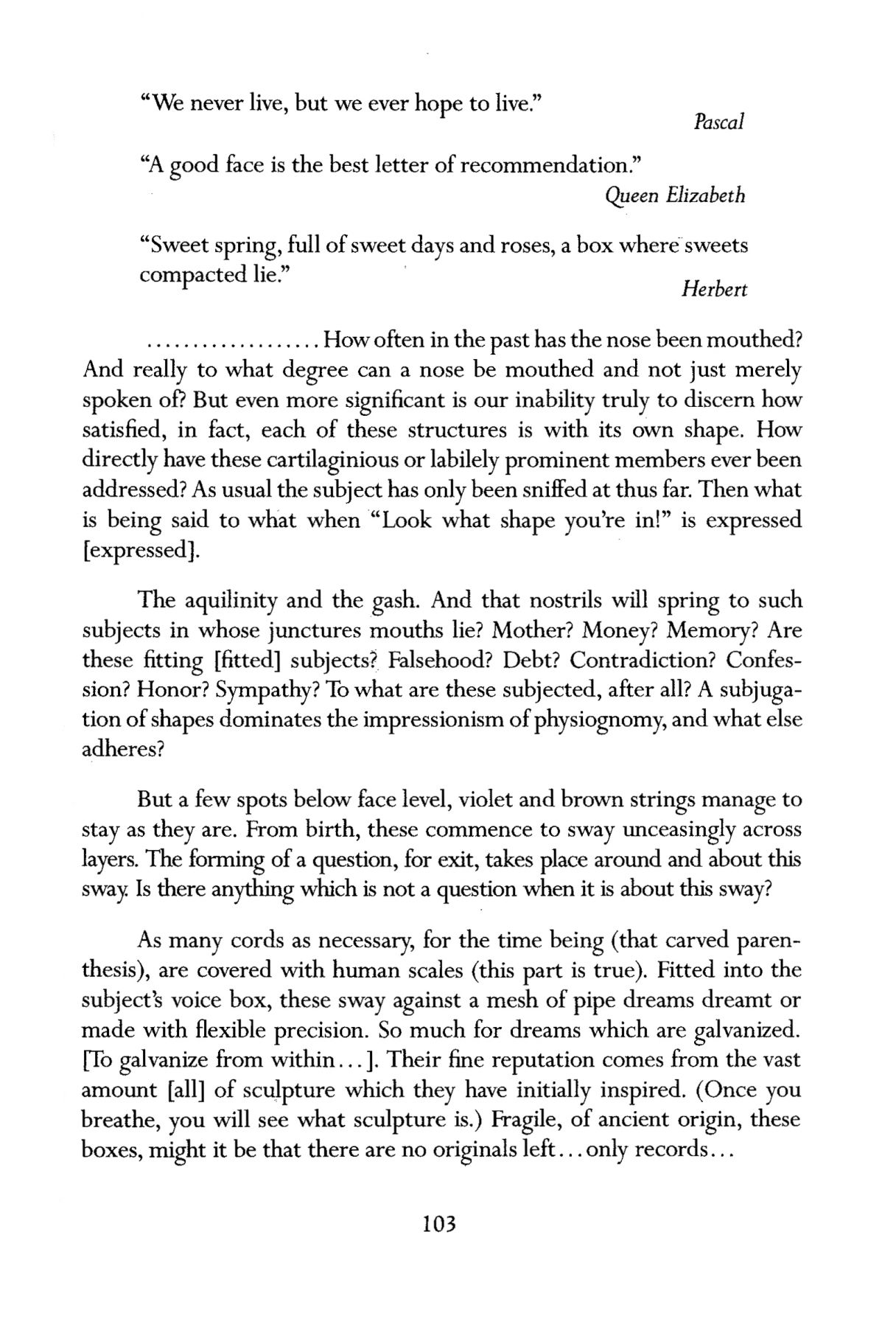

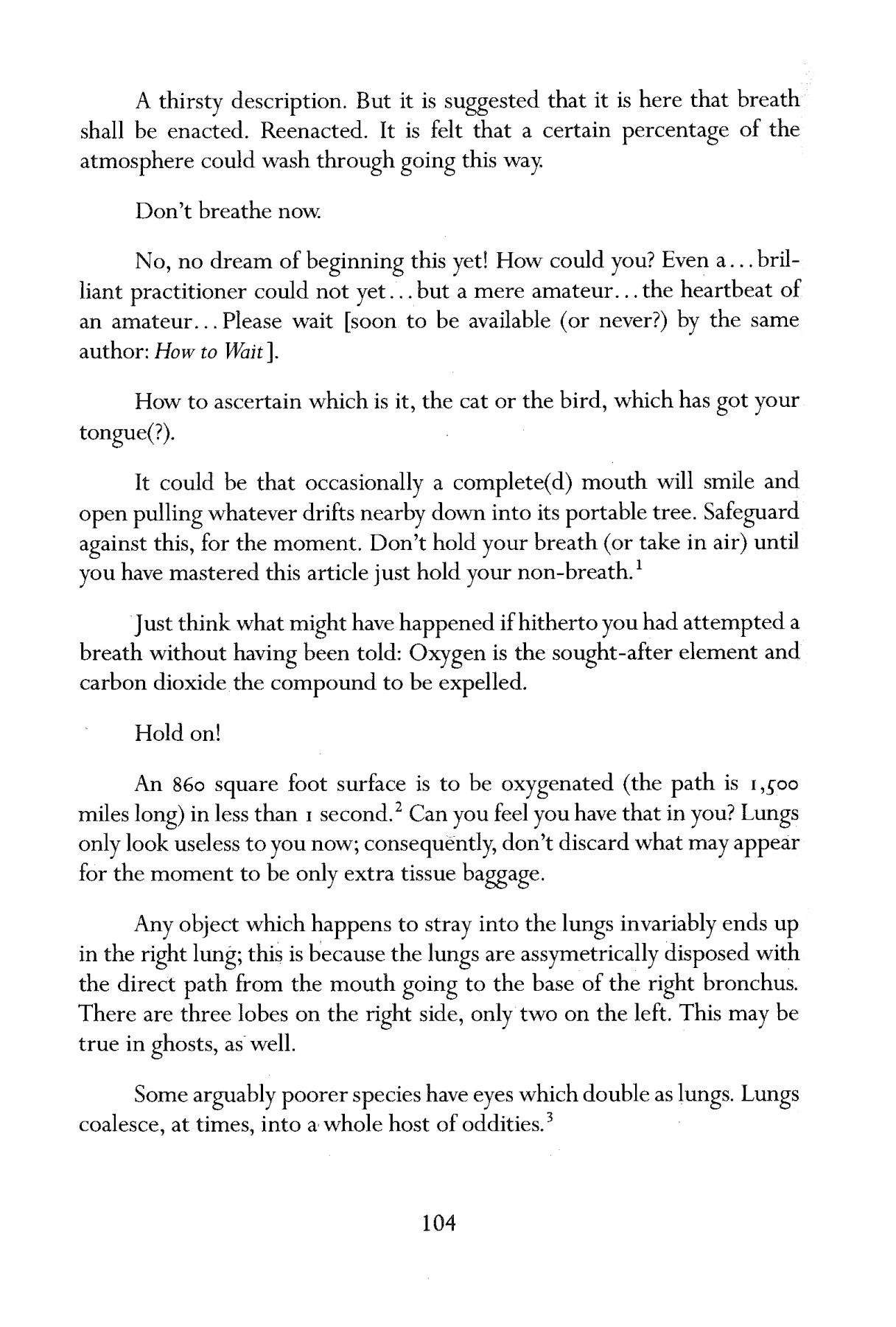

What the President Will Say and Do!! (1984) by Madeline Gins could easily be read as a series of essays written for the present moment. Gins’s short entry on “How to Breathe”, a part of a longer essay entitled “All Men are Sisters”, seems especially poignant when taken as a potential approach to the current socio-political upheaval. This includes the hyper-alert way we are experiencing the physical act of breathing as something essential that now comes with an added sense of danger during an airborne pandemic. As narrator, Gins is instructing her readers on how to best go about breathing against the backdrop of the political primary season before the election in 1984. Gins takes care to advise the reader in the first few sentences not to start breathing until she has explained how to do so properly, lest they “too willingly succumb to the contaminated will engendered by the gay abandon of the societal rot of centuries.” In no less than fifteen steps, she goes on to describe the bodily system of breathing through the mouth or nose and into the lungs using poetic prose, avoiding those banal names for parts of the body. Gins has us focus in on the minutiae of something we do automatically, often without thinking about it, over the next two pages. Possibly without the reader even realizing it, she leads us through something quite common in 2020 – a breathing meditation, in which she eventually begins to question who the subject doing the breathing is. What else is this process of breathing subjected to, Gins asks:

Mother? Money? Memory? Are these fitting [fitted] subjects? Falsehood? Debt? Contradiction? Confession? Honor? Sympathy? To what are these subjected, after all? A subjugation of shapes dominates the impressionism of physiognomy, and what else adheres?

Each breath during inhalation asks a question, perhaps one of the above, and each exhalation provides time and space for an answer, a process Gins suggests starts at birth. We might take in one of the items in Gins’s above list as we hold in our breath, with the option to let some or all of it remain a part of us before releasing it. Gins describes the breath as a “sway”, back and forth or in and out, that now encompasses our dreams. These dreams are “galvanize[d] from within”, by which Gins might mean an electric spark flows through them, igniting them and spurring them on, but by the next sentence they are solidifying into sculptures that they have inspired, perhaps literally. Each breath, then, becomes a dream and a sculpture, in this case if not literally, then as records of sculpture of “ancient origin”, evoking Ovid’s tale of Pygmalion, who breathes life into a statue of his own creation, making Galatea, his dream, come alive. Each breath becomes a “reenactment” of such ancient events, bringing atmosphere in and then pushing it out.

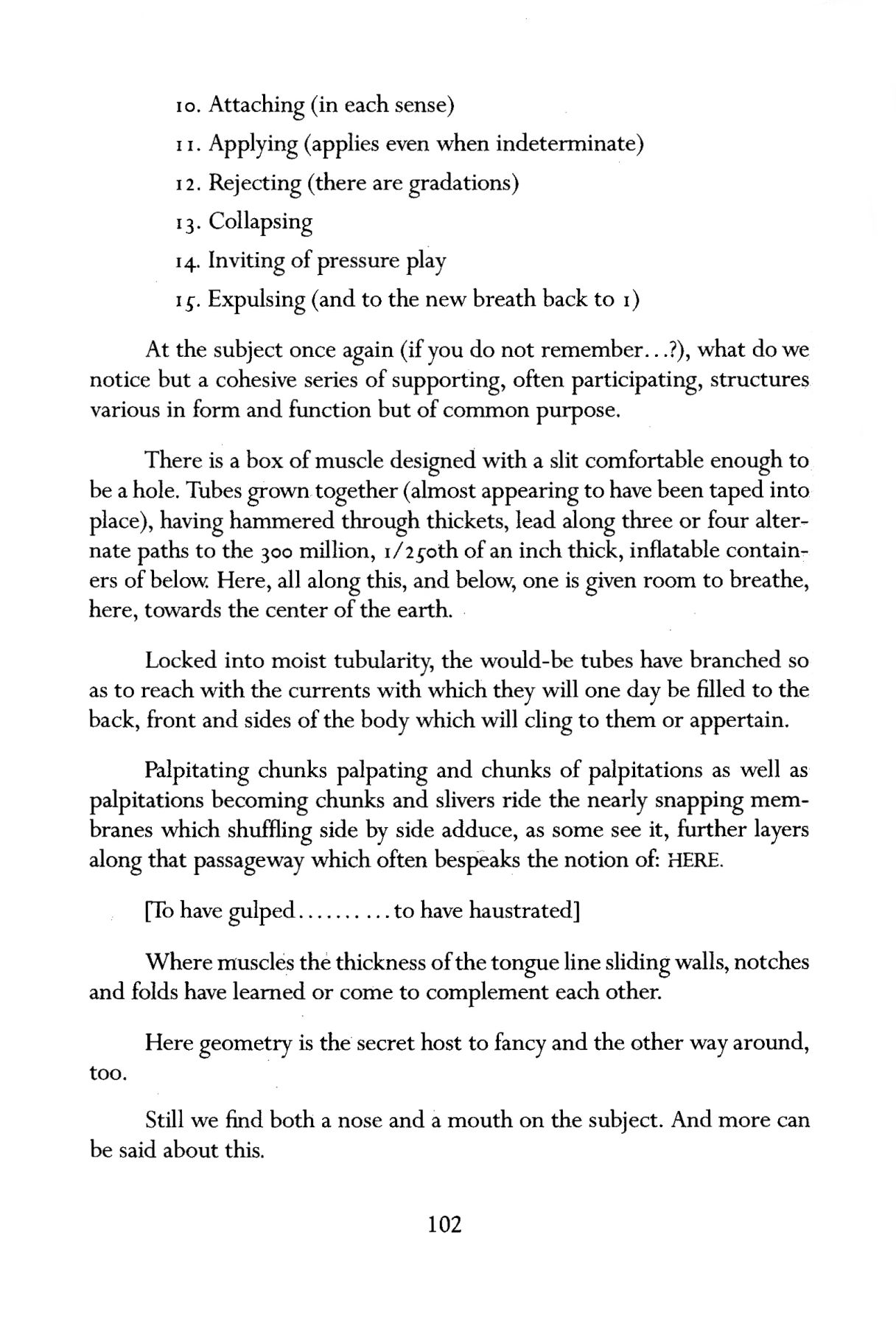

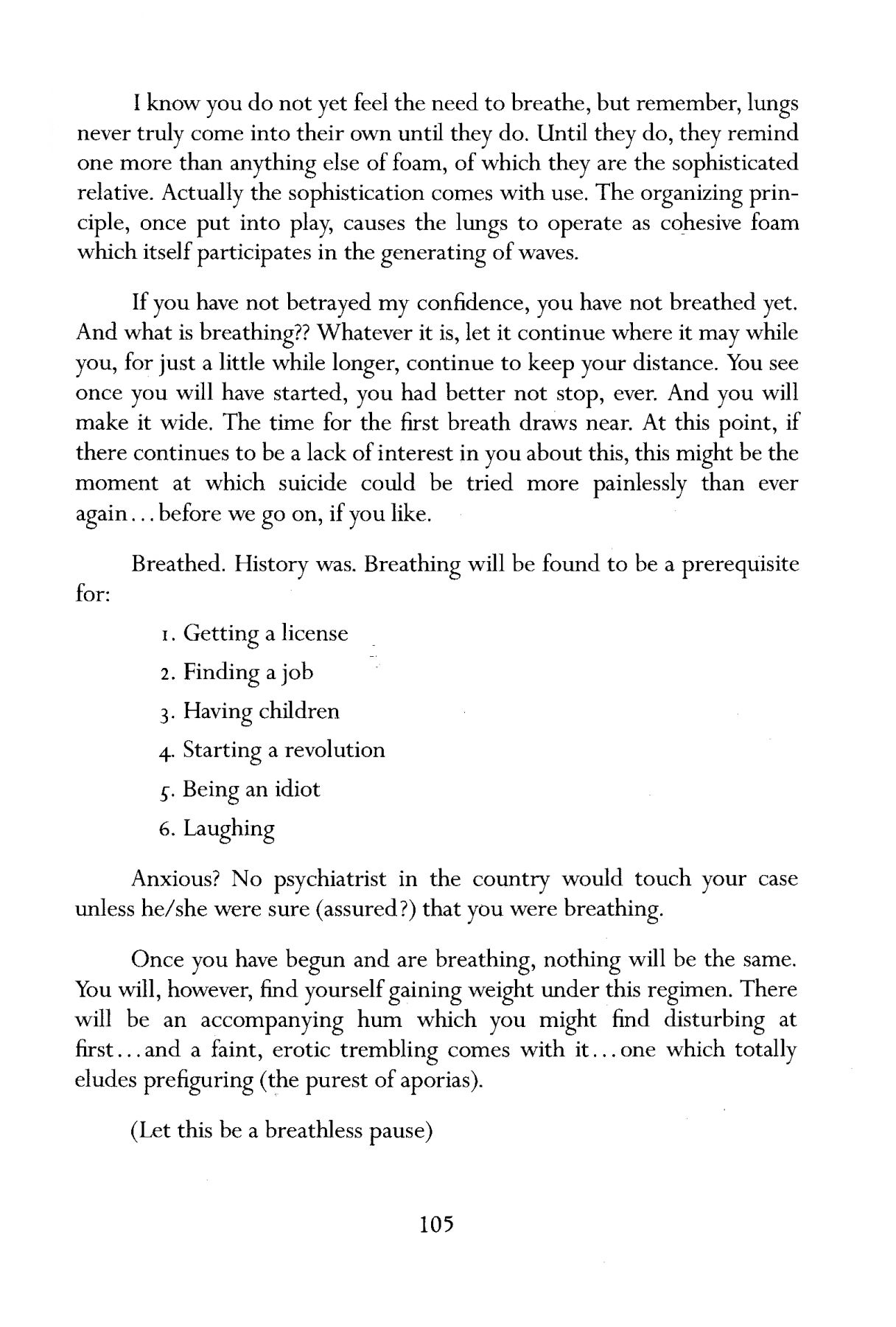

At this point, Gins cautions that the reader is still not ready to breathe. They do not even know yet, for example, that they should take in oxygen, and expel carbon dioxide. Are we able to read this as a metaphor? Before we act, we need to be sure of what precisely it is that we want to keep and make use of from each experience, and what we need to let go. Gins goes into some specific physiological detail at this point: “An 860 square foot surface is to be oxygenated (the path is 1,500 miles long) in less than 1 second” (referring to the lungs, this is a bit alarming to consider if we are thinking of an airborne virus). She asks us to consider carefully whether we can feel this process inside of us or if we think our lungs are useless appendages. We learn here that lungs are asymmetrical, with three lobes on the right and two on the left, for “ghosts too”, and that they can coalesce with other parts of the body in other species. Regardless, lungs are useless unless you use them. They gain “sophistication” and “generate waves” once engaged.

We have not yet taken a breath, if we have followed her instructions carefully, but we now learn that we have been breathing all along, unaware and separated from the experience. In reality, having followed this breathing meditation, we have been preparing ourselves to make a choice: do we remain passive and stay in a relatively painless state, or do we choose to engage, becoming active creators of our own lives?

Breathed. History was. Breathing will be found to be a prerequisite for:

1. Getting a license

2. Finding a job

3. Having children

4. Starting a revolution

5. Being an idiot

6. Laughing

We might rightfully add voting to this list.

The moment to breathe has arrived, but it comes with a warning:

Once you have begun and are breathing, nothing will be the same. You will, however, find yourself gaining weight under this regimen. There will be an accompanying hum which you might find disturbing at first…and a faint, erotic trembling comes with it…one which totally eludes prefiguring (the purest of aporias).

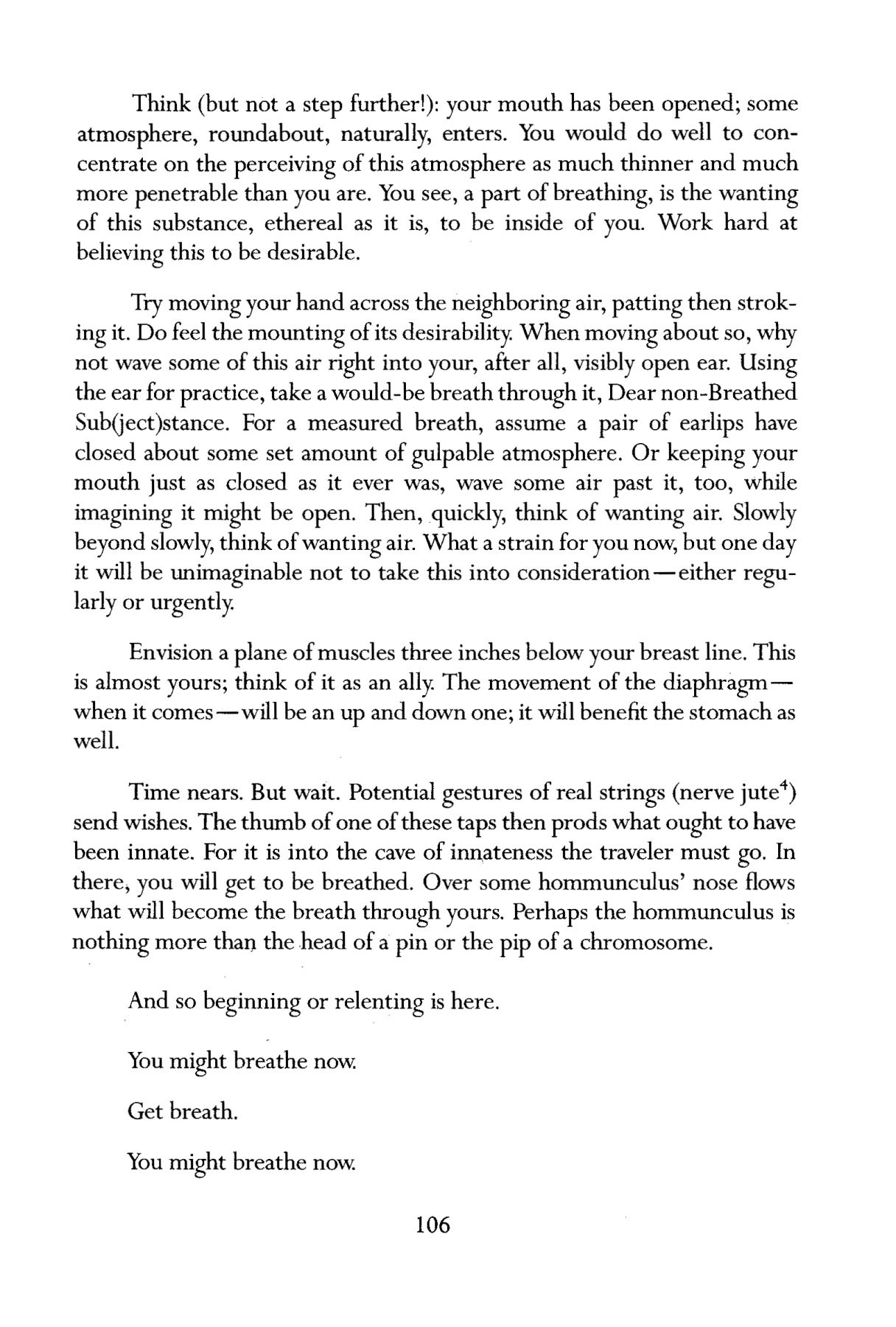

In thinking of our current moment, this weight gain is perhaps the result of being active and engaged in civic life, taking on more worry and responsibility than you would get with just the passive act of taking breath in and out. An anticipatory anxiety appears with no discernible shape that might allow us to puzzle out what comes next. If you are ready for this, Gins suggests it is time to open your mouth and just see what it feels like to let some atmosphere in, but not actually inhaling, maybe practicing by waving it into your ear. Then think of desiring that air, wanting to pull it in with the movement of the diaphragm, up and down. With a slight delay as you grasp that the knowledge of this procedure must be innate within you and is about to happen alongside the first gasp of your earliest ancestor, “[y]ou might breathe now.”

We breathe with Gins for the duration of the next page and she asks us to “determine the instant in which breath first started in [us]” while we were reading her text. We might not have been aware that it was happening, but at some point, if we look back, the text will “appear fogged”, a clear indication that we were indeed breathing. How to move “through” breathing, Gins informs us, is another question best left for the “experts”, but she has now instructed us on “in and out”. She leaves us with a final question: “Never in, one enters, as today, but once put out, how can one ever get back in?” This sentence is a bit curious, since we have just been focusing on breathing in and out in succession. It is true, though, that each breath is composed of a specific sampling of air and is therefore always different from the next. The lungs take it in, use the oxygen, and expel carbon dioxide – something you can never breathe in again. If we take away one thing from this text for our present time, perhaps it should be that each individual moment is unique, and we can choose to either engage or not engage with it, but, regardless, the opportunity will never again present itself in this precise way, except in the larger sense that all time is cyclical. All each moment asks of us is that we breathe it in, let it ask its question, and then consider it and let it go in the time and space of our exhalation. We can choose to feel its weightiness for as long an interval as we wish, but we always release it as we prepare for our subsequent steps with the next breath of fresh air. Hopefully, breathing with Gins has left you inspired.