Dear Friends,

In honor of Madeline Gins’s birthday on November 7th, the fourth edition of Ambiguous Zones focuses on one of her unpublished books. Madeline considered two possible titles that sum up the content quite well: “Conversations for our time: poet and physician” or “Medically in Our Time.” This book is based on a series of interviews that Madeline carried out with doctors with a variety of specialties, including neurology and psychiatry, an acupuncturist, and patients. Her overarching goal was to provide a course of action for the patient/reader that would help them navigate different approaches to their healthcare, including standard medical care, alternative therapies, vitamin regimens, and care related to their mental health, whether through psychiatry or other mind-body modalities like meditation and hypnosis.

Help us celebrate Madeline’s 80th birthday by doing whatever mind-body exercise speaks to you the most.

Yours in the reversible destiny mode,

Reversible Destiny Foundation and ARAKAWA+GINS Tokyo Office

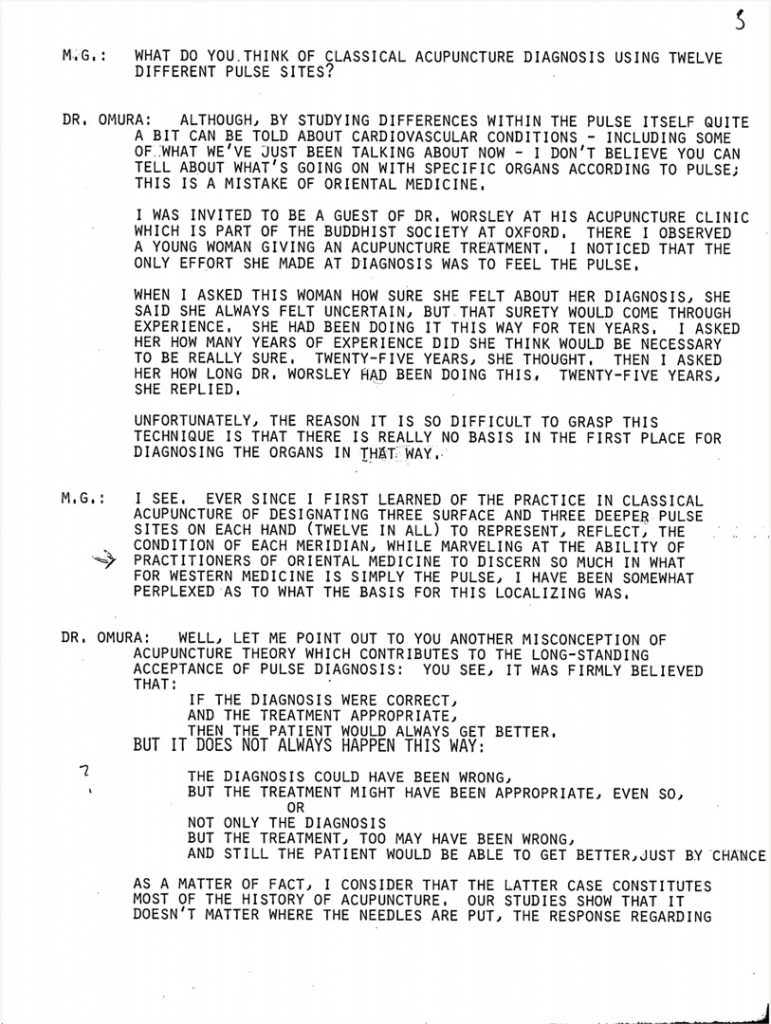

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Madeline Gins conducted multiple interviews with a variety of doctors and patients over the course of five years for a book that she would never publish. Her goal was to approach the evidence surrounding various treatments for disease from a poet’s perspective. To Madeline, this meant “keeping intuition in play” while sorting through all of the information. In her proposal, Madeline also makes clear that her approach was not simply “a ‘holistic’ patchwork, but a unified way of knowing.” What she seems to be suggesting is that, as a patient, you would not just go separately to your endocrinologist, acupuncturist, psychiatrist, and another doctor or physical therapist for biofeedback. The poet would make sure all of these approaches were working together in harmony – something you yourself might be able to do after reading Madeline’s book.

In the 2020s, we have even more access to information than Madeline would have been able to dream of in the 1970s/1980s. At the touch of our fingertips, we can find an unending stream of articles and websites that may offer insight into what ails us, otherwise known as “Dr. Google.” We come away with way too much, often contradictory, information, and this was precisely the instance in which Madeline thought a poet could help. In our current time, the wellness industry is in full-swing, which means there is yet more advice available now that may have been considered more esoteric , though available if you sought it out and paid for it, in the last quarter of the twentieth century. A doctor will have their advice, using a scientific approach geared toward physical symptoms, an acupuncturist will look at the problem from a different perspective, and so on. Regardless of the source, a poet can synthesize all the evidence to come up with the best course of treatment, using every avenue available. In Madeline’s words,

When poetry succeeds, through the medium of intuition (a set of suspicions in the process of being confirmed) what is known comes to be easily apparent. In the kind light of poetry, whatever is picked up and brought forward may come to be so bathed in enthusiasm, that it will virtually glow with what it knows, so that what was once difficult to resolve takes place almost effortlessly.

One of her proposed titles for the book, “Medically in Our Time”, was inspired by the eleventh century poet and physician Ibn Sina, or Avicenna as he was known in Latin, who wrote The Poem of Medicine. Ibn Sina also wrote the Canon of Medicine, but he felt that his poem was more easily transmissible—easier to understand and memorize. Ibn Sina reviewed previous scholars on the subject of medicine and well-being, including Hippocrates and Galen. Madeline set out a similar task for herself in writing her own book. On the wellness side of things, Ibn Sina stressed the importance of taking care of the soul, which would include good company and music if someone was sick, and for general preventative care, moderate exercise.

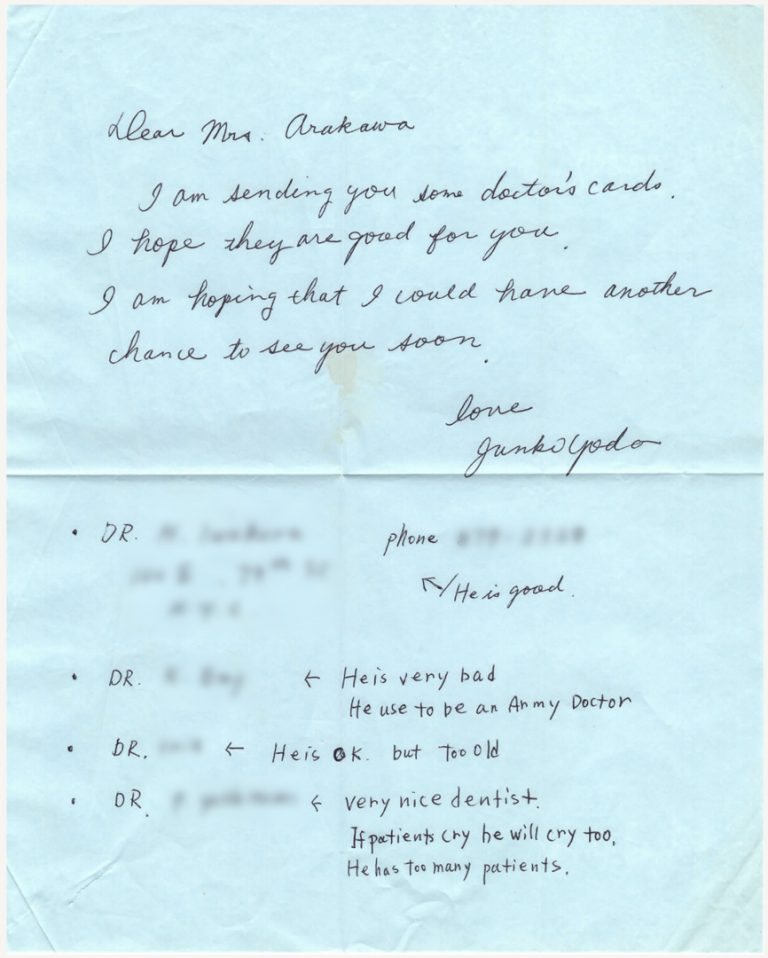

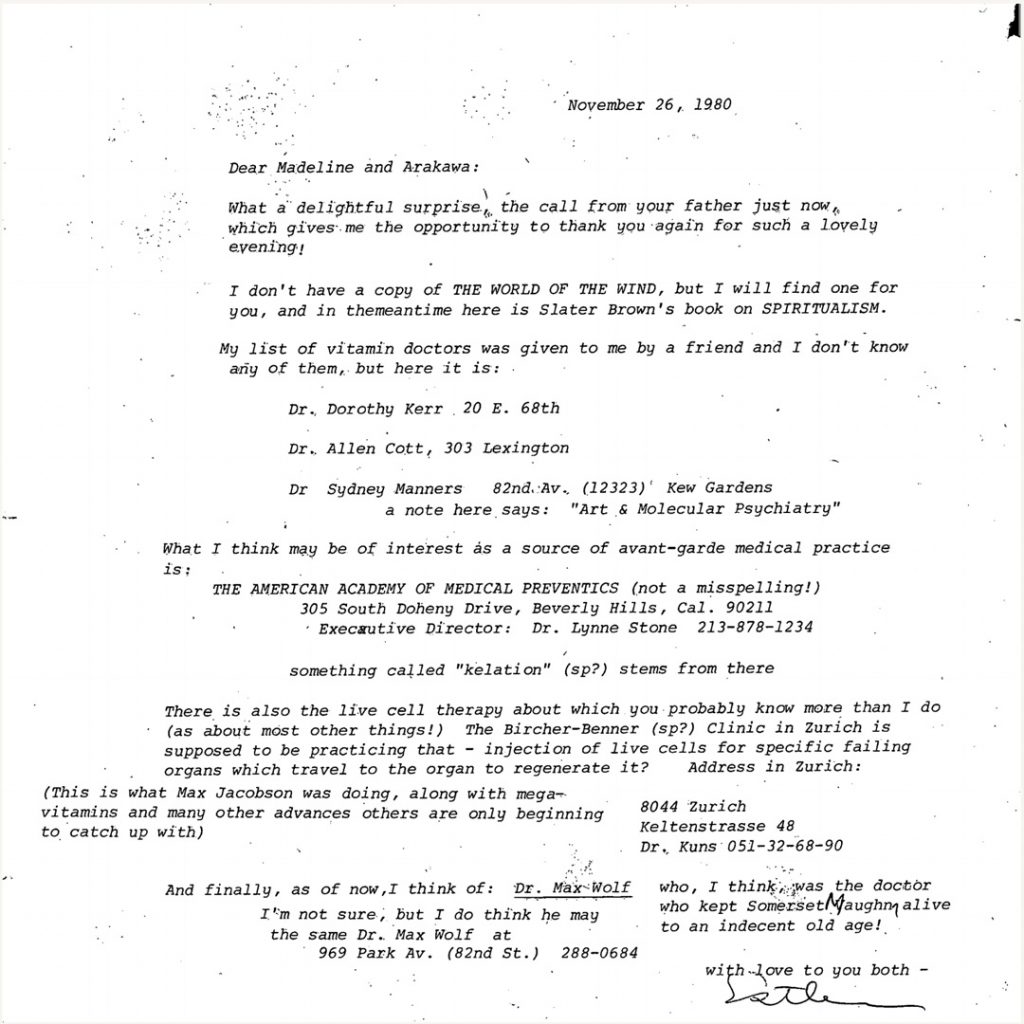

Madeline conducted an extensive search for doctors who would be willing to sit down for an interview. Aside from reading articles and books written by doctors whom she then would track down, Madeline also asked friends and acquaintances for suggestions and collected names and numbers. One of her parents’ friends gave her a number of names of “vitamin” doctors. Another friend gave a list of Japanese doctors with a short description of each. She also received a number of doctor business cards from obliging friends. By including specialists, general practitioners, doctors focused on research, and patients, Madeline’s own research covered as many view points as possible.

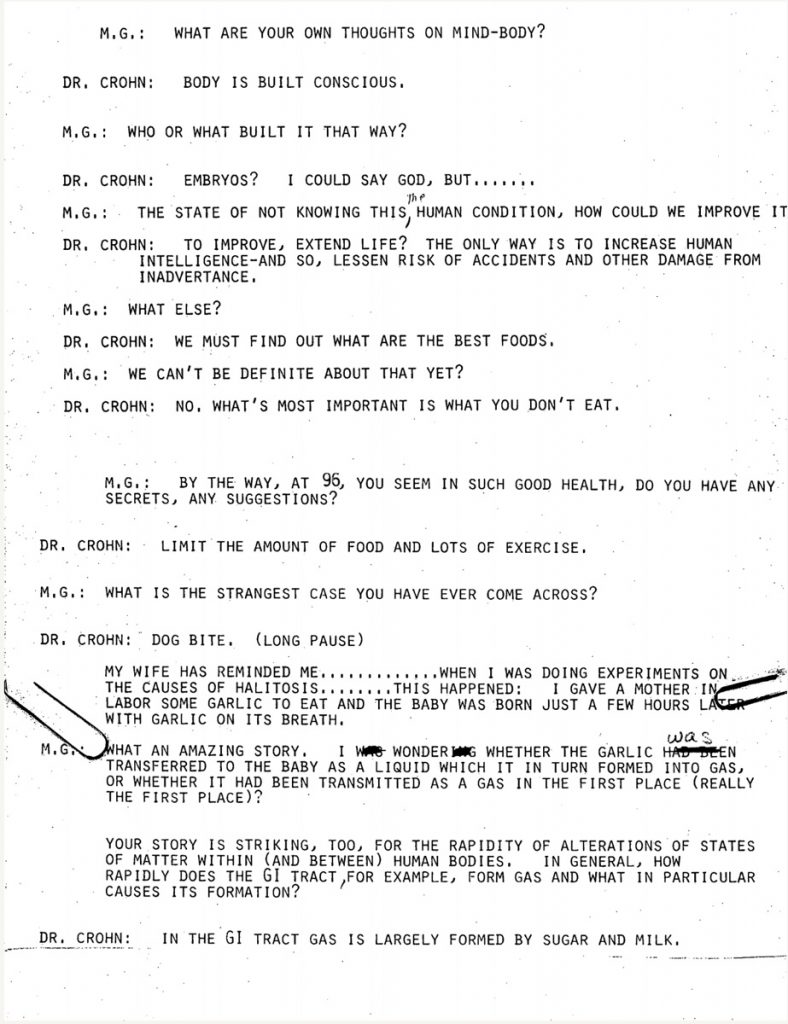

While a poet’s response to or opinion about medical treatments is not something people tended to search out at the time, or now for that matter, Madeline invoked Avicenna to remind everyone that there were indeed other periods in time when the ideas of a poet and a physician were intermingled, and she started by asking the same questions, in essence, that he did. For example: “what do you think of the state of medical research today?” “What about diet?”

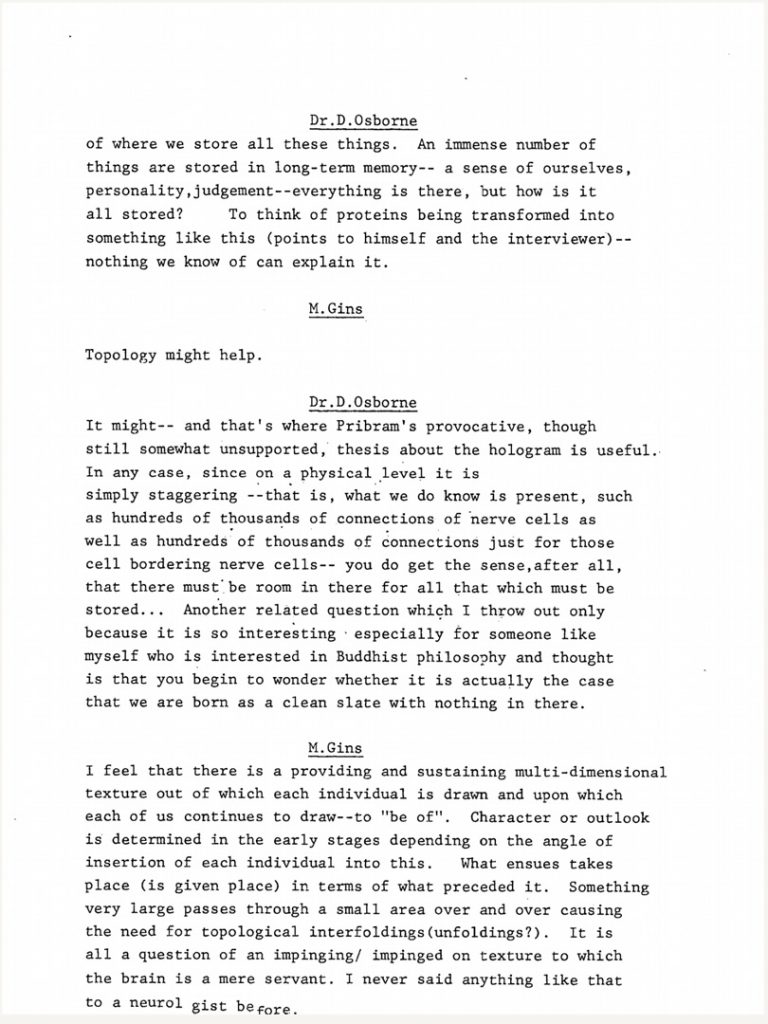

Madeline’s approach to the interviews sought to engage her conversant on a poetic level and this seems to have allowed some of the doctors the space to speak about certain not obviously medical motivations they may have had that would not have come up in a typical interview session. One neurologist in particular opened up about his interest in Buddhist philosophy as a source of inspiration for one thread of his research. This created a rather productive discussion about some of Madeline’s more philosophical ideas, including topology.

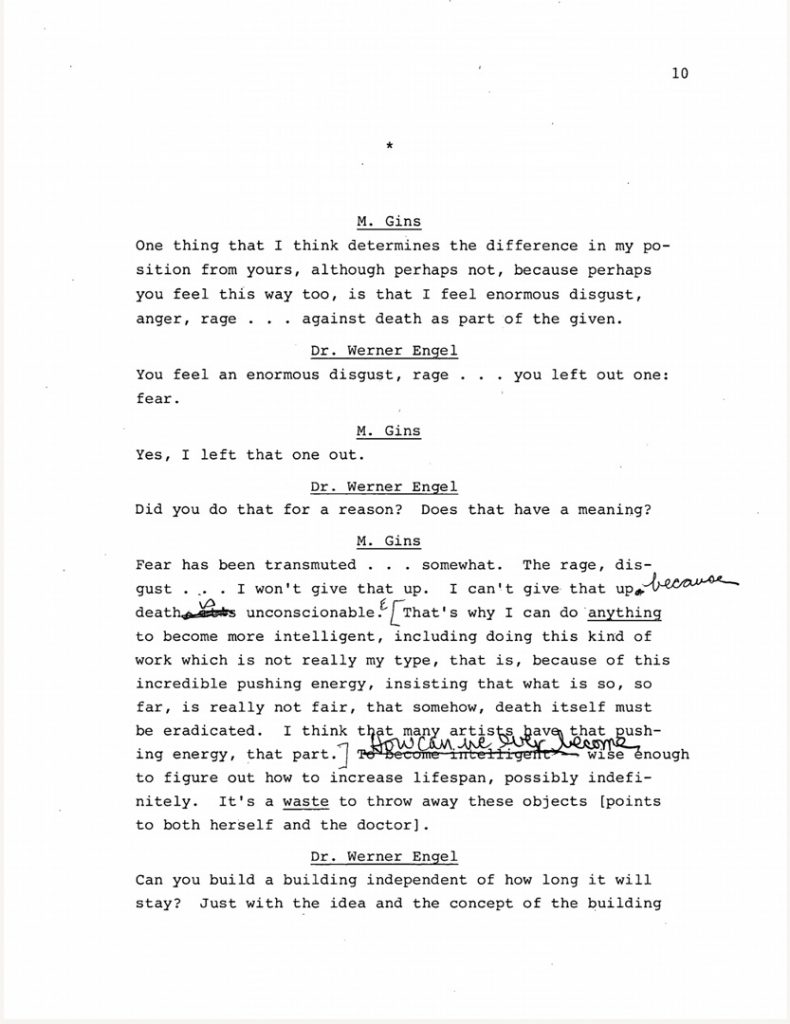

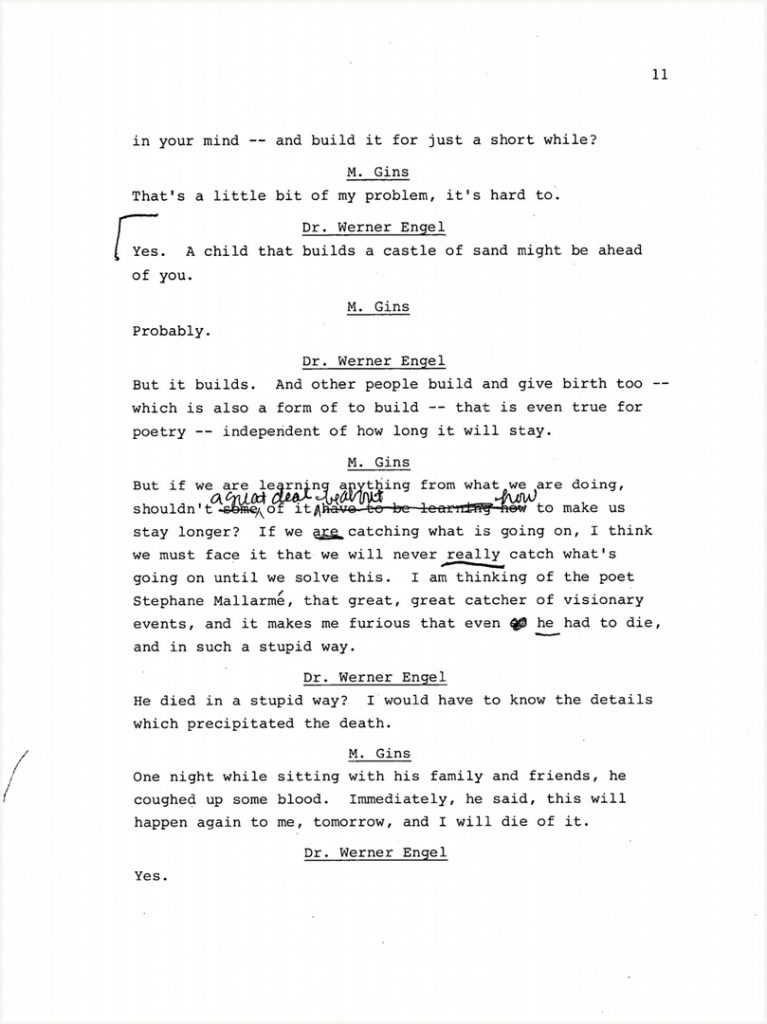

In a conversation with a psychiatrist and Jungian analyst, Madeline is offered another way to address her anger over death: is she able to build a building with the idea and the concept of the building in her mind, but build it just for a short while? Dr. Engel says that “independent of how long [the building] will stay,” you build. A child building a sandcastle understands this clearly.

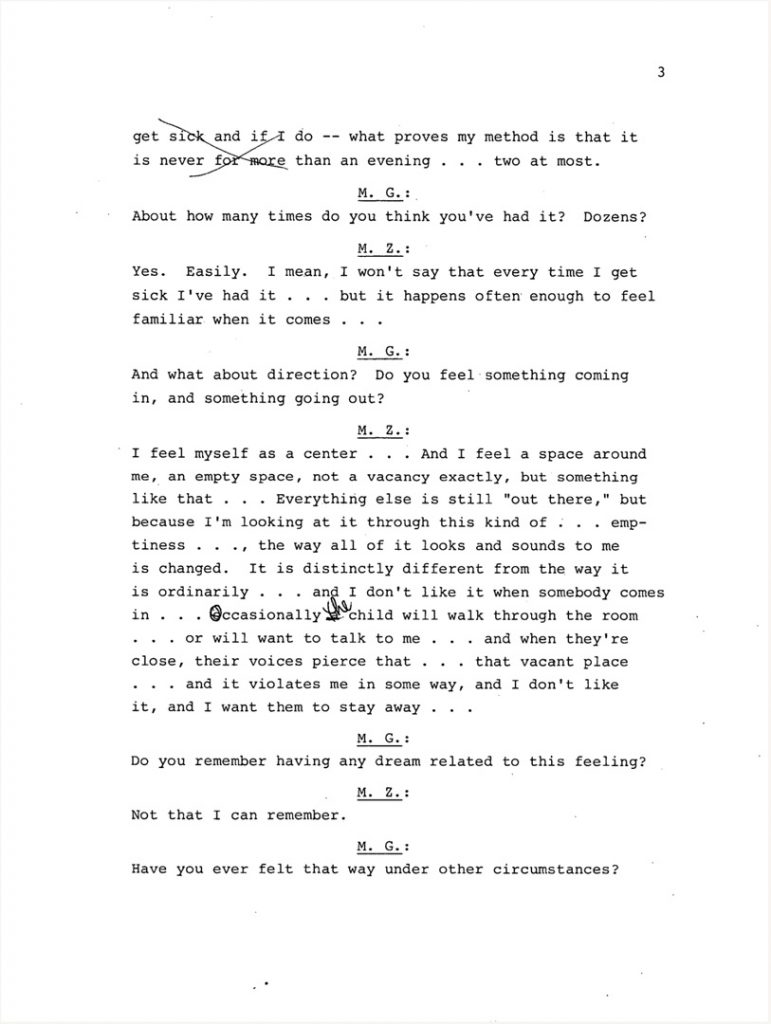

When in conversation with a patient, Madeline channels her poetic-alchemical voice to offer a way of navigating through difficulties. Through a series of interesting questions, she is able to help a patient visualize her well-being as a space both in and around her, while becoming more aware of what happens to her experience of time during episodes of illness.

In this way we see the poetic voice as one that is highly adaptable. Madeline, as the author, moves from medical researcher, to questioner, to philosopher, to psychologist, to the analyzed patient. It feels quite seamless when reading through her conversations, edited for flow, and even in its incomplete, unpublished form, this book provides not only an interesting look at what was happening “Medically in [Madeline’s] Time”, but also at the human condition and how it responds to and copes with the struggle, in its various manifestations, for wellness. Throughout the interviews, Madeline seems to be circling the idea that the body inherently knows what to do to get better, the struggle becomes access to this knowledge. How do you break past conditioned thought patterns and the mind, which seem designed to keep us from what our body knows? We can look for Madeline and Arakawa’s attempts to answer this question in the vast majority of their projects, both realized and unrealized.

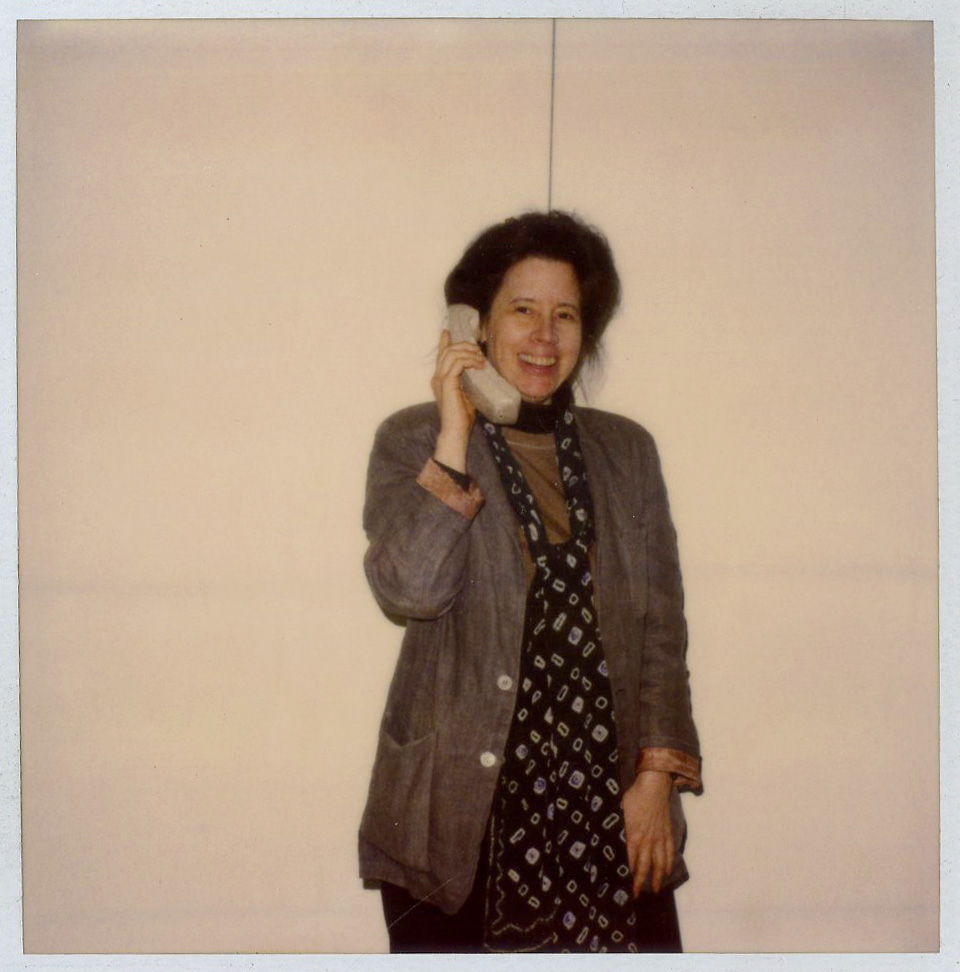

Top image: Madeline Gins on the telephone, ca. late 1980s

Lower images: Correspondence between Madeline Gins and various health professionals and patients