Dear Friends,

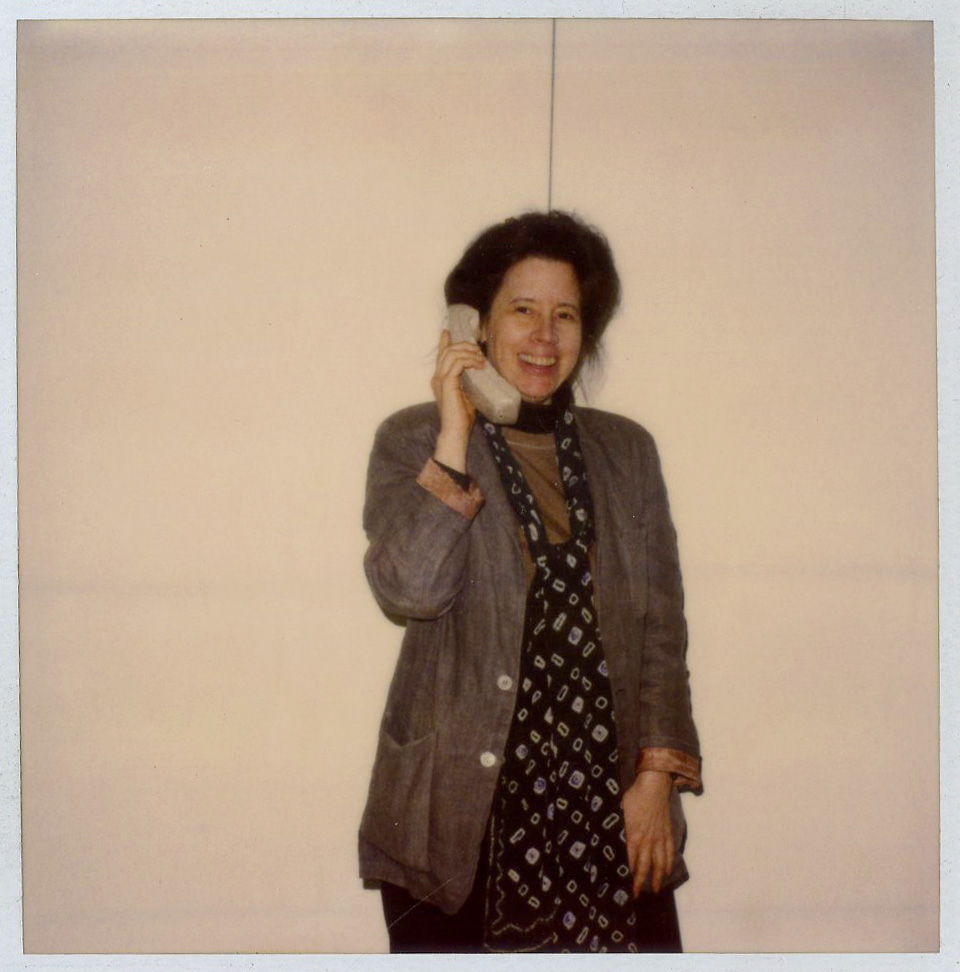

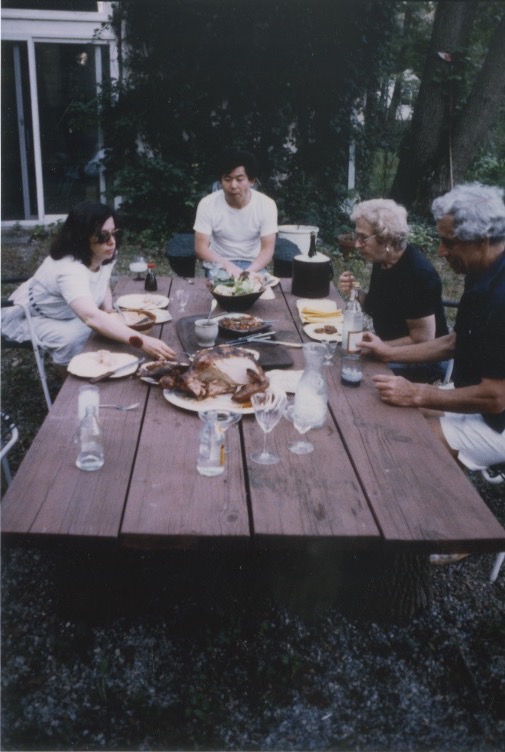

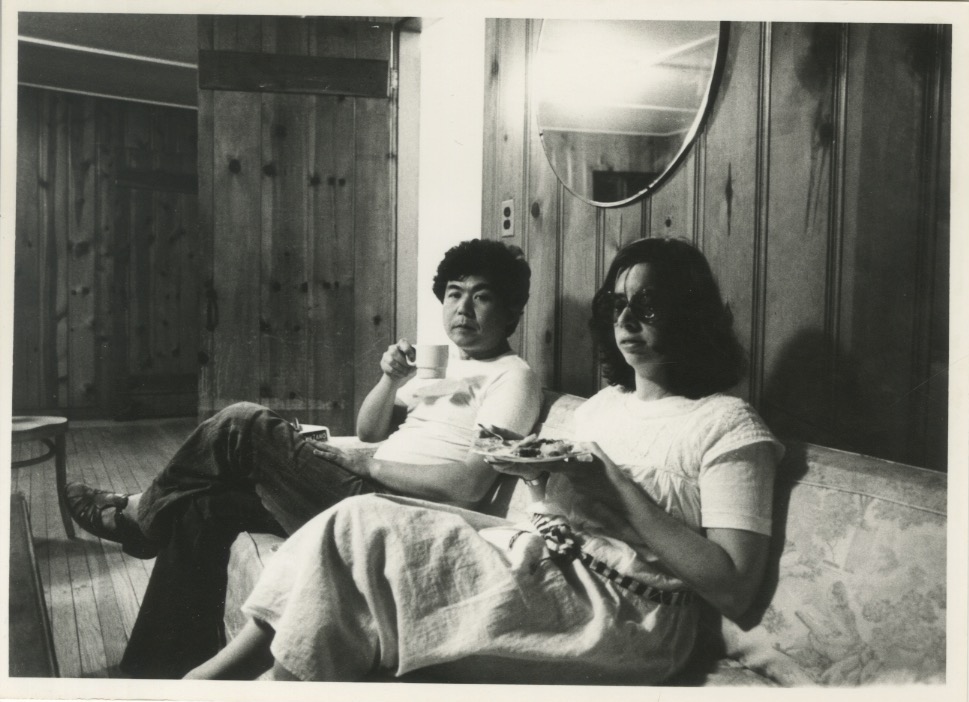

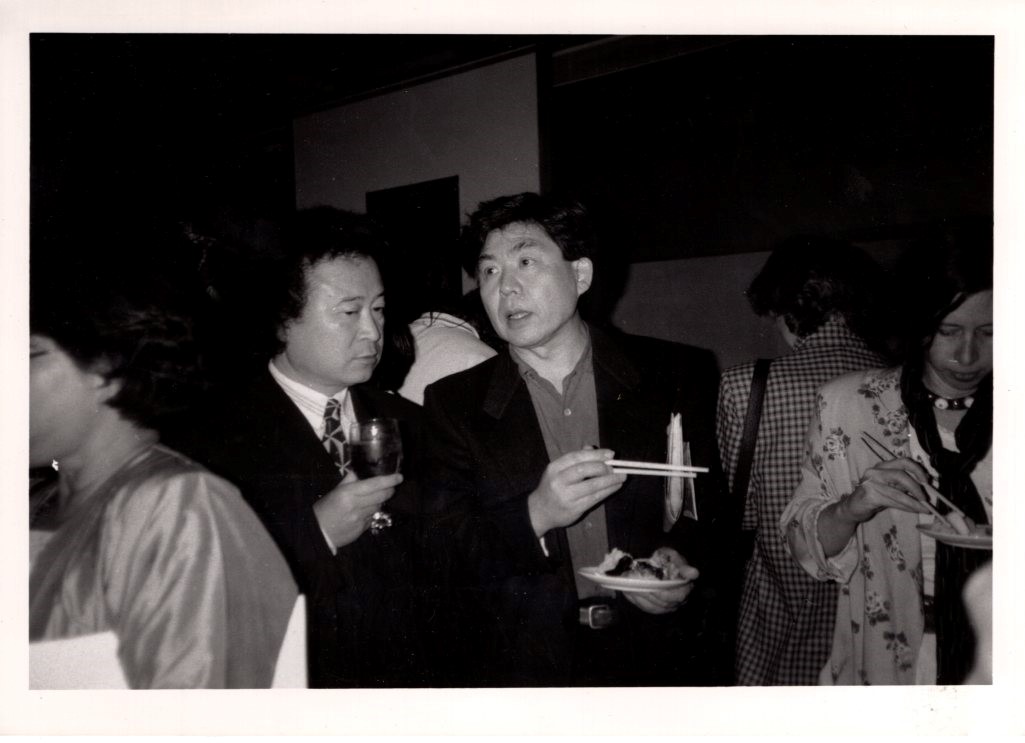

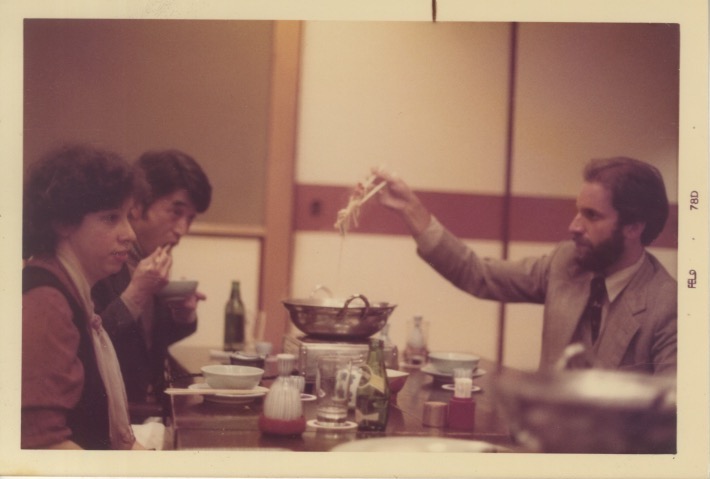

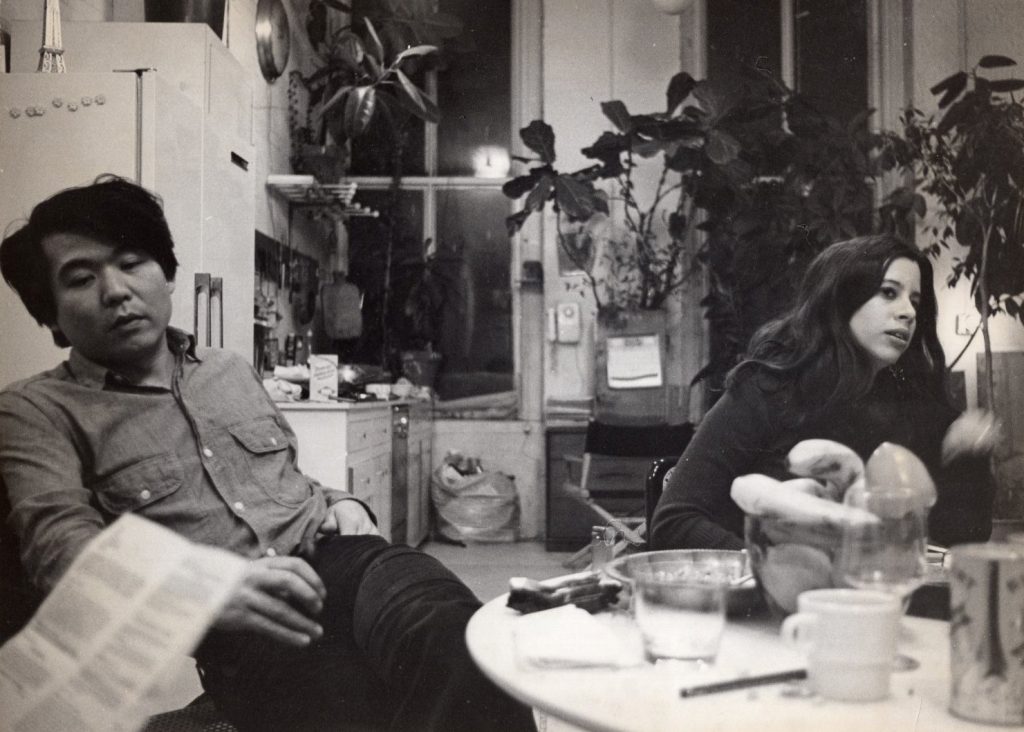

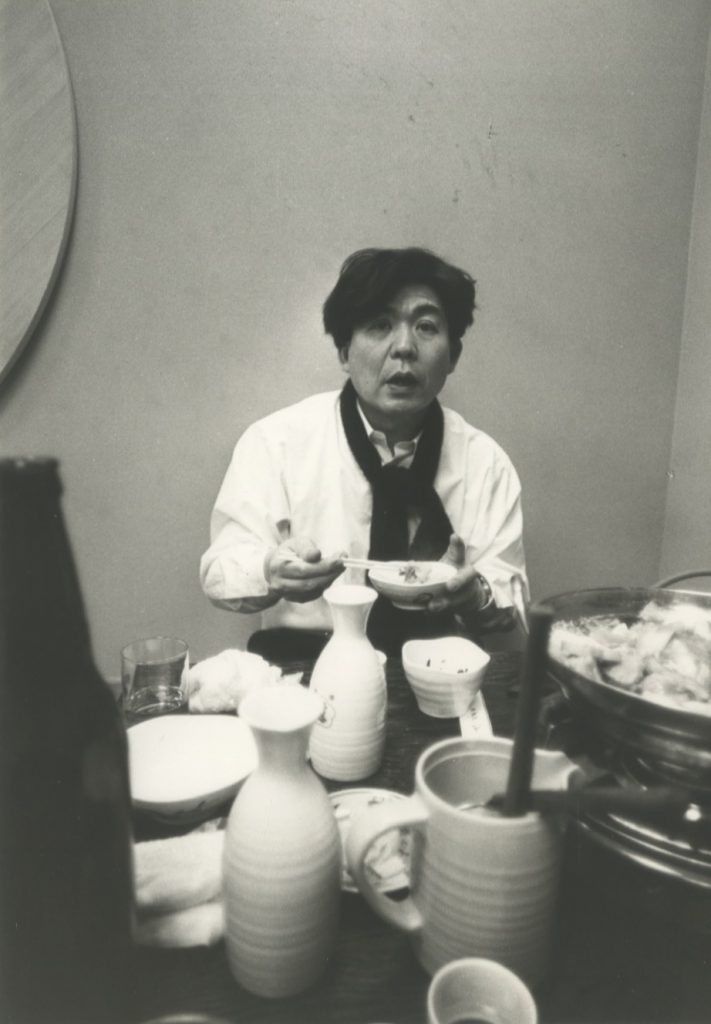

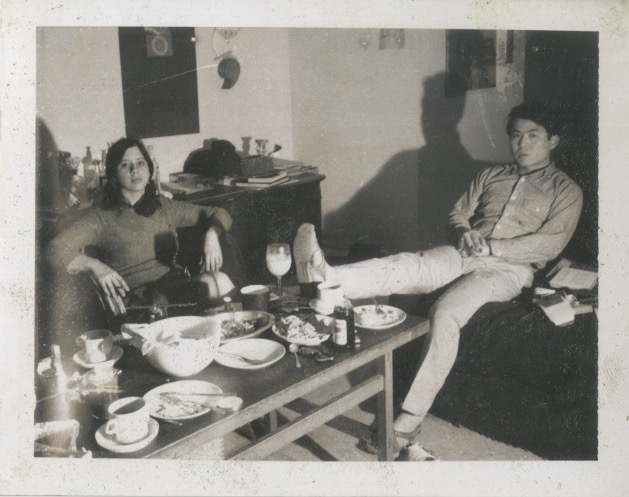

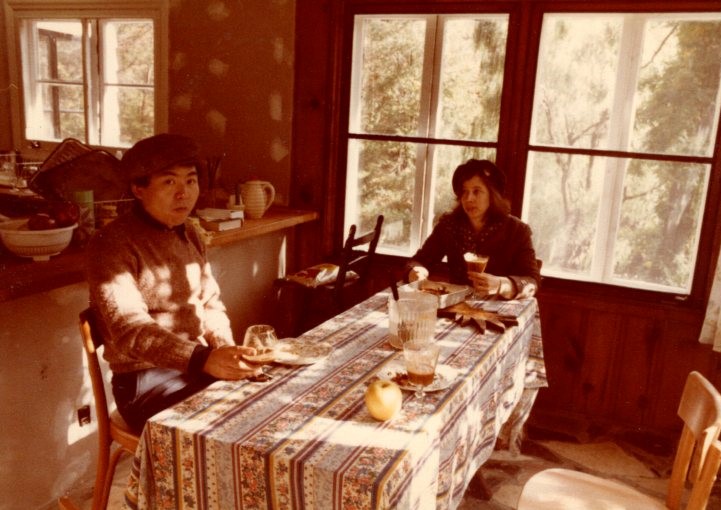

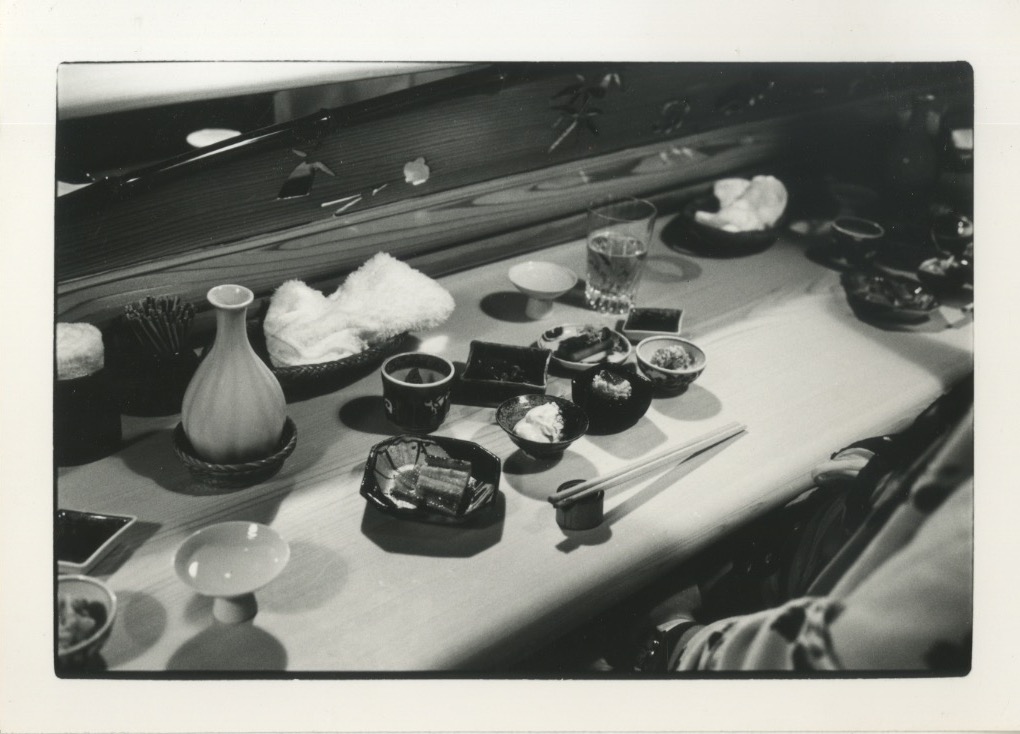

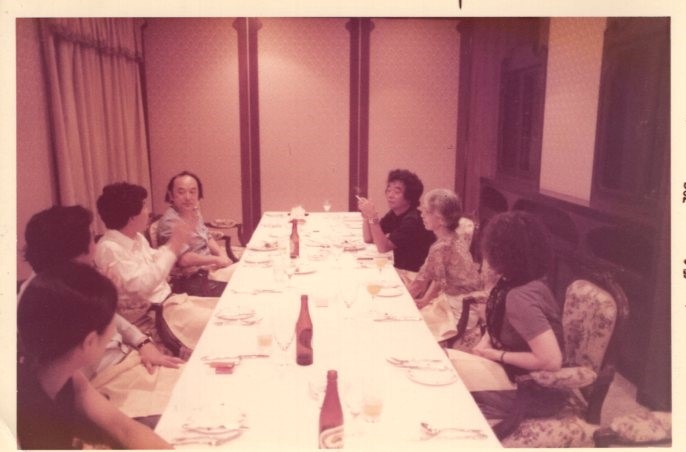

This fifth issue of Ambiguous Zones arrives partway into the holiday season. Like last year, the final few weeks of 2021 may not feel quite the same as previous years, but that is all the more reason to focus on spending time with loved ones, whether in person or online. The RDF archive has no shortage of photographic evidence that Madeline and Arakawa did just that year round. Regardless of how your celebrations shape up this year, we hope these photographs of Madeline and Arakawa dining with friends and family get you into the festive spirit!

We also hope you will join us virtually for Dr. Ignacio Adriasola’s lecture and tour of the exhibition ARAKAWA: Waiting Voices, live from Gagosian Gallery in Basel on December 9th at 11am EST (click here to register in advance).

In the meantime, we are sending warm wishes for a lovely December!

Yours in the reversible destiny mode,

Reversible Destiny Foundation and ARAKAWA+GINS Tokyo Office

Top image: Thanksgiving in July, or a heatwave or somewhere warm in November? Madeline Gins, Arakawa, and Madeline’s parents, Evelyn Gins, and Milton Gins enjoy turkey (or duck?)

in the great outdoors, ca. 1977.