Dear Friends,

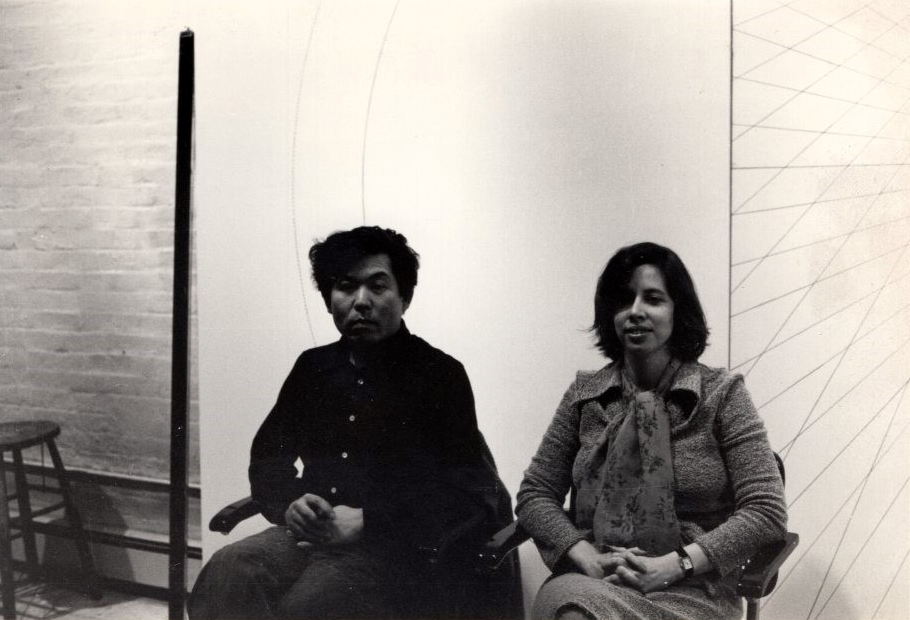

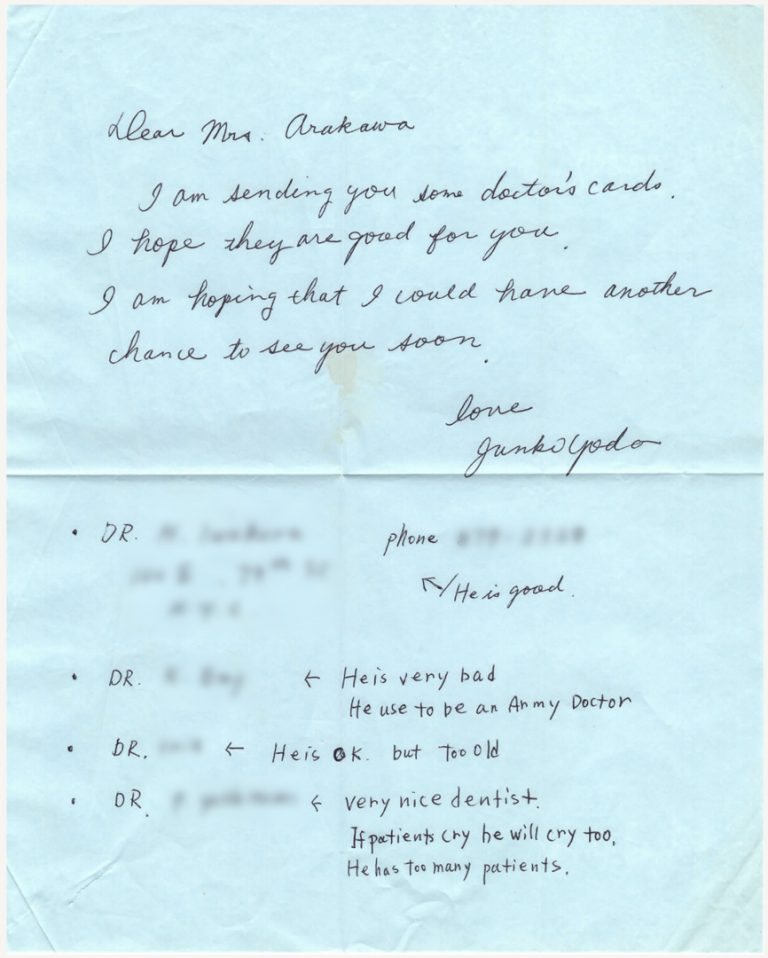

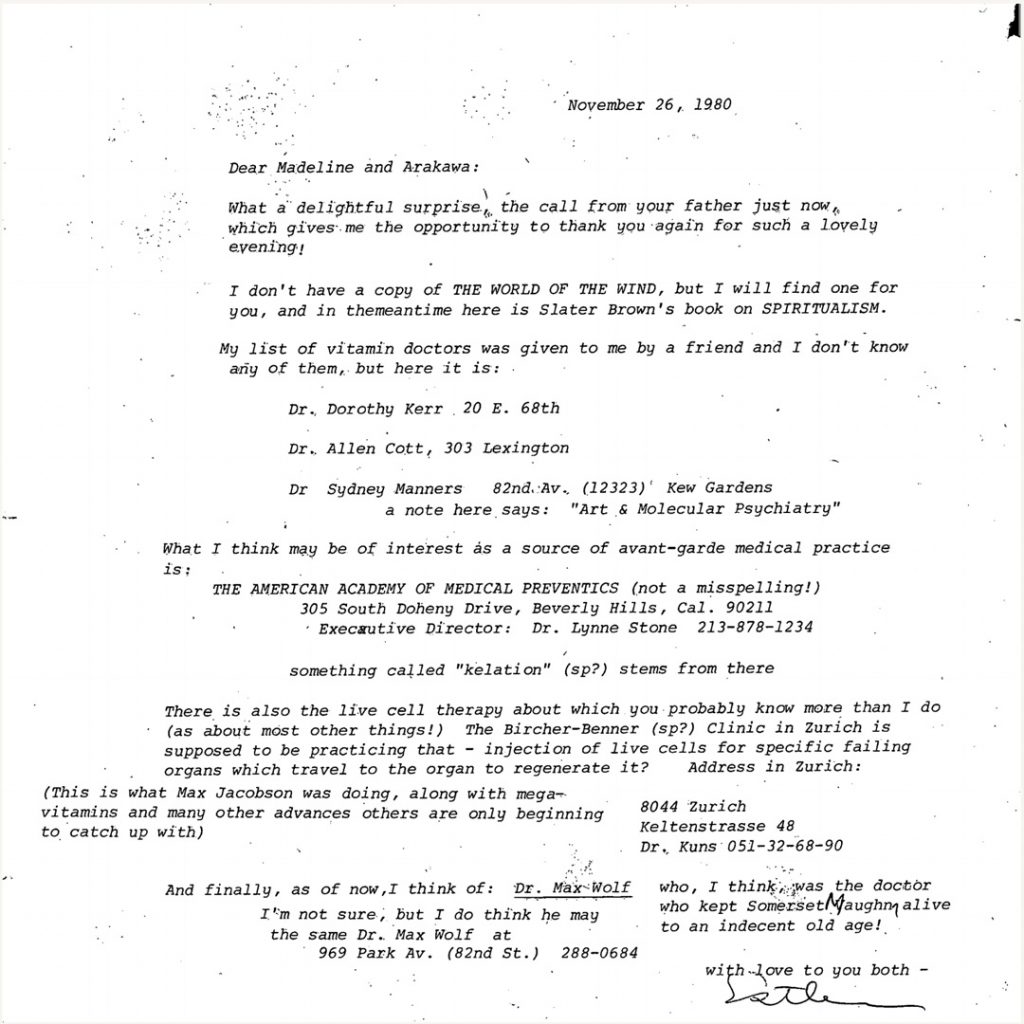

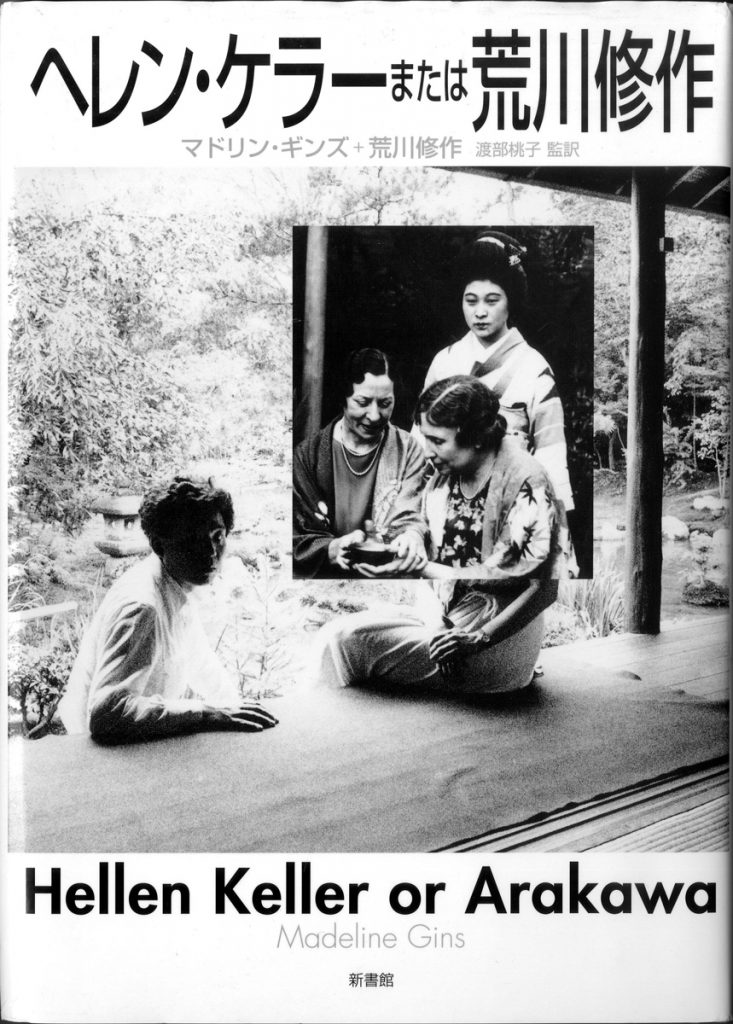

As we begin to wrap up 2023, we are pleased to bring you Ambiguous Zones, 15, written by our Graduate Fellow Emiko Inoue, whose essay centers on Arakawa’s film Why Not: A Serenade of Eschatological Ecology (1969). Emiko is a masters student in the Art History Department at Hunter College, CUNY. Supported by The Feminist Institute Research Award, she is currently completing her masters thesis on the Japanese woman artist Mitsuko Tabe. In this essay, Emiko employs the interpretive approach of art critic Junzo Ishiko, a contemporary of Arakawa, as her guiding framework for examining the unique relationship between Arakawa’s 1960s paintings and Why Not. We hope you enjoy this thought-provoking investigation into Arakawa’s elusive and enigmatic film.

Yours in the reversible destiny mode,

Reversible Destiny Foundation and the ARAKAWA+GINS Tokyo Office

In-Between Human and Objects in Arakawa’s Why Not: A Serenade of Eschatological Ecology (1969)

By Emiko Inoue

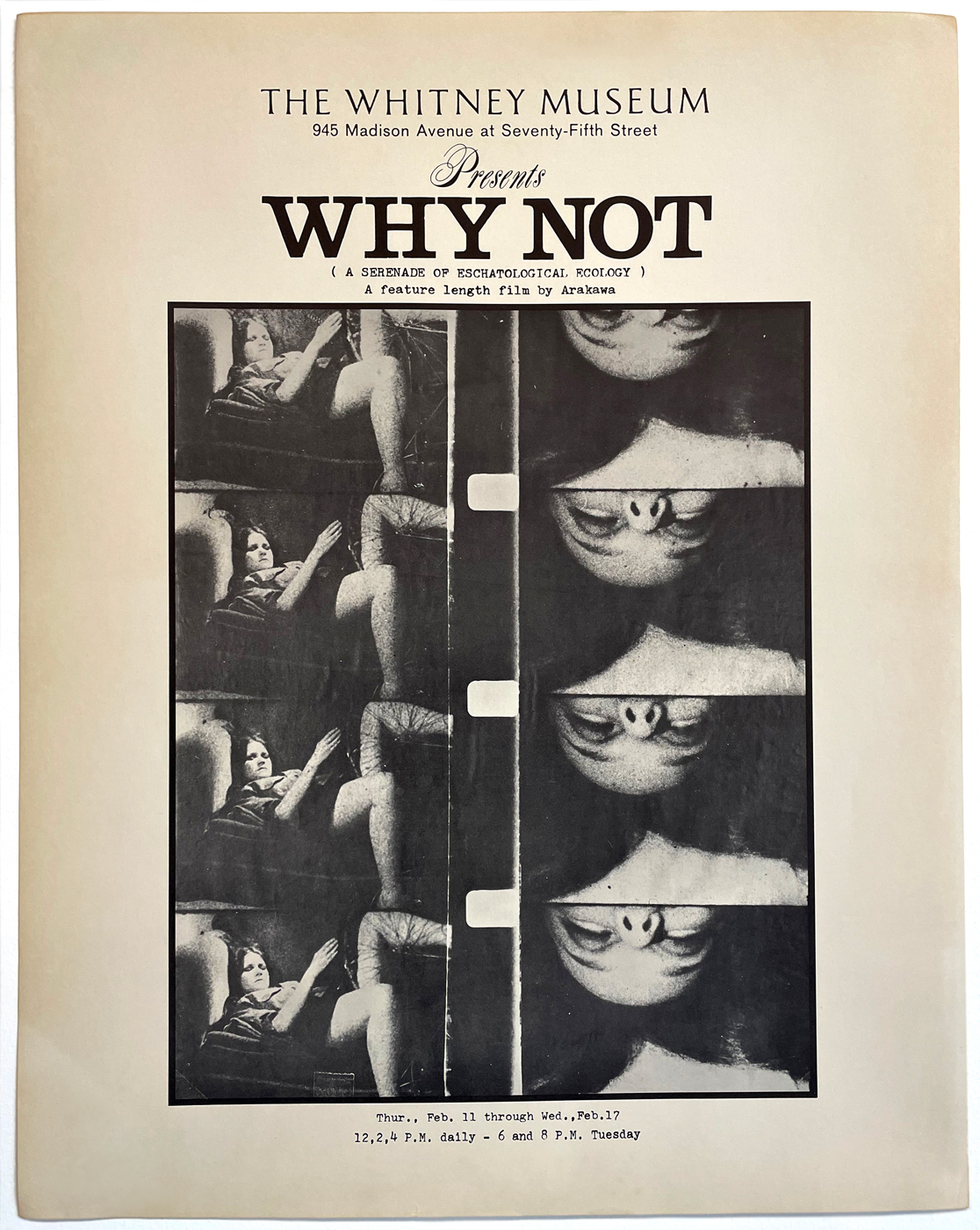

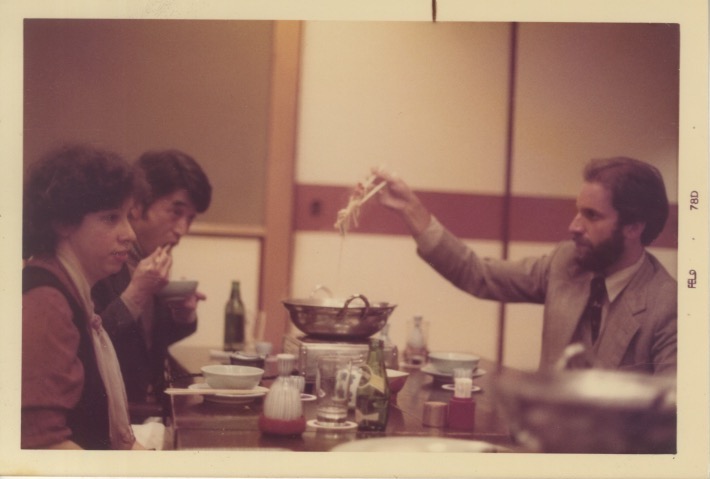

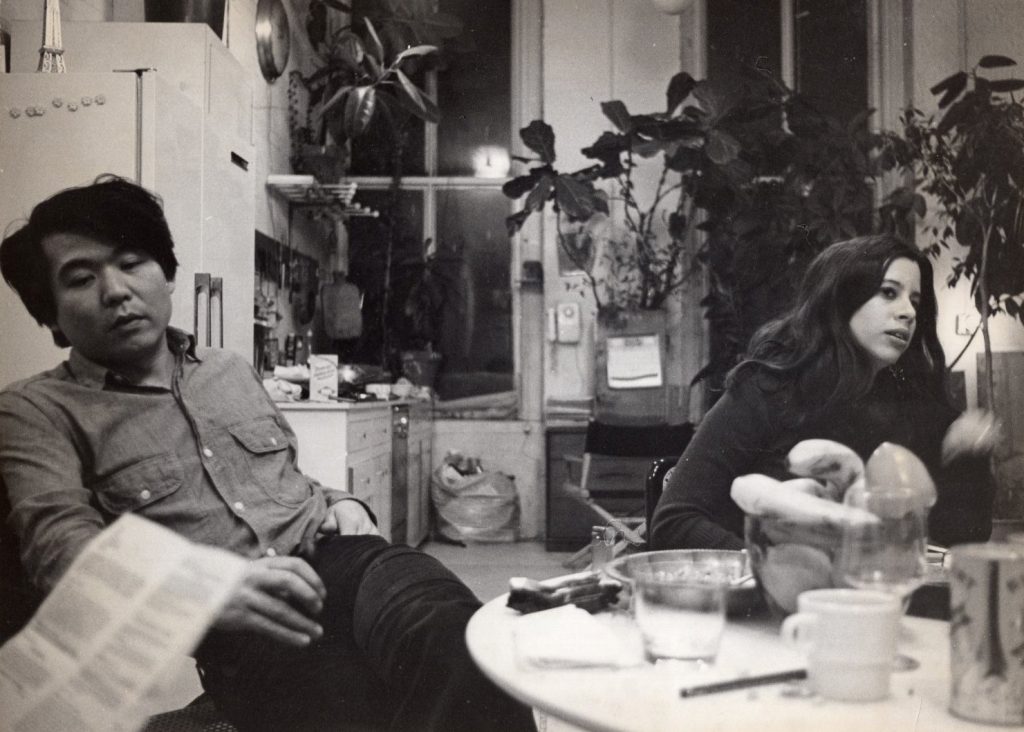

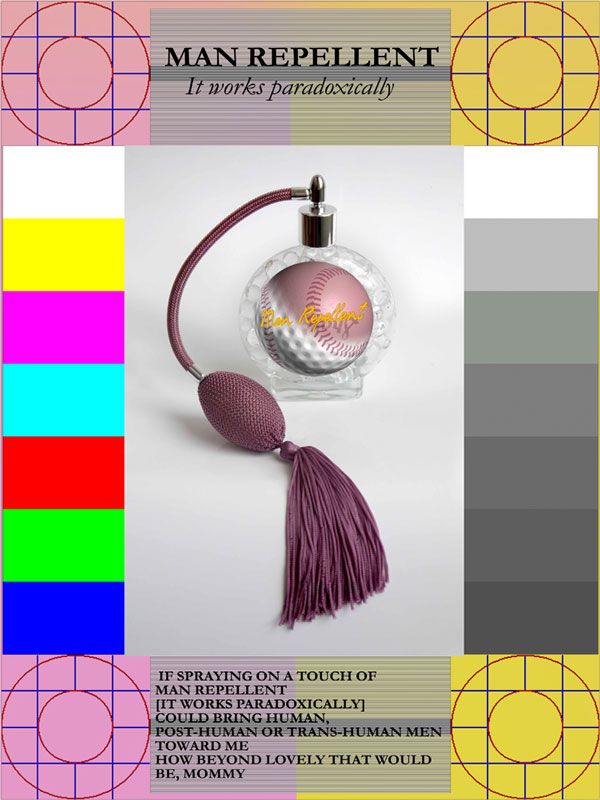

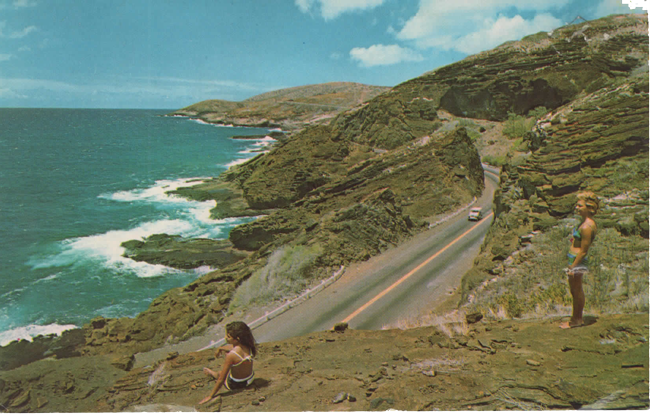

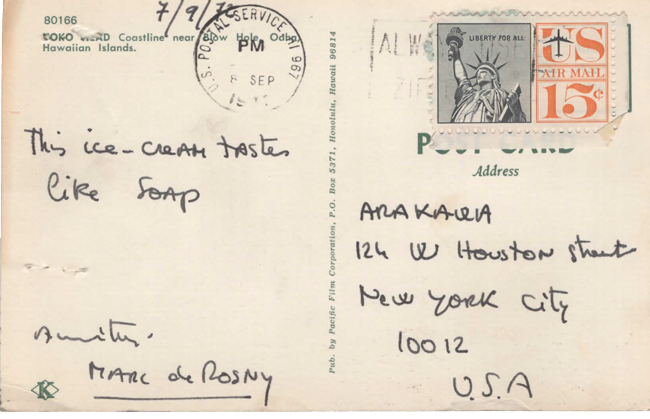

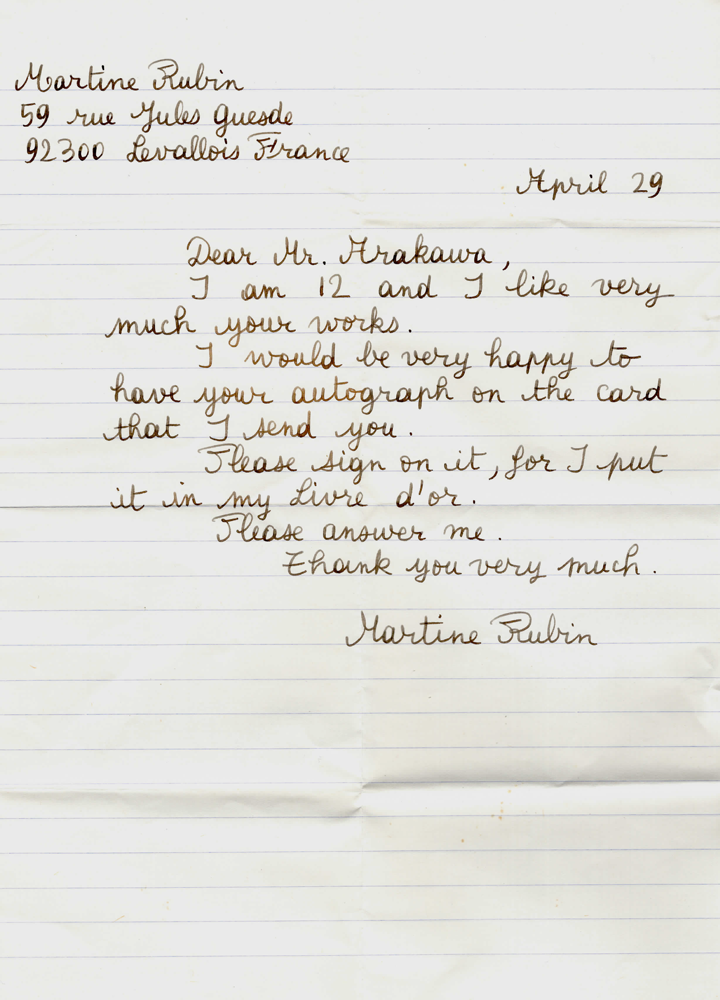

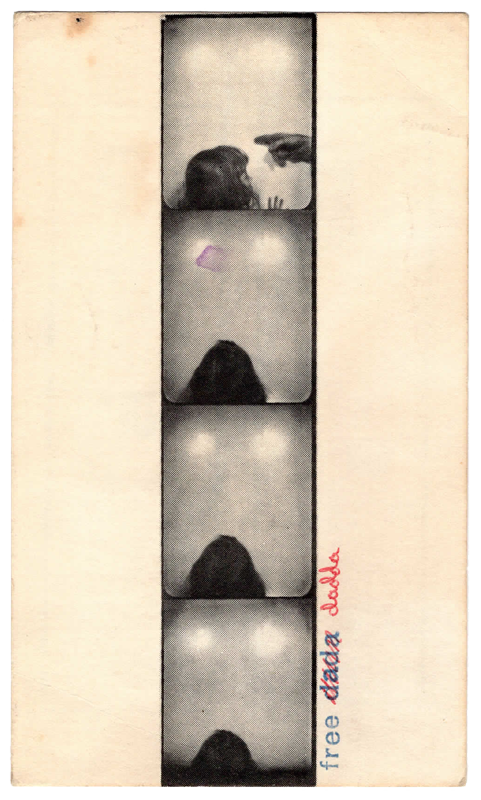

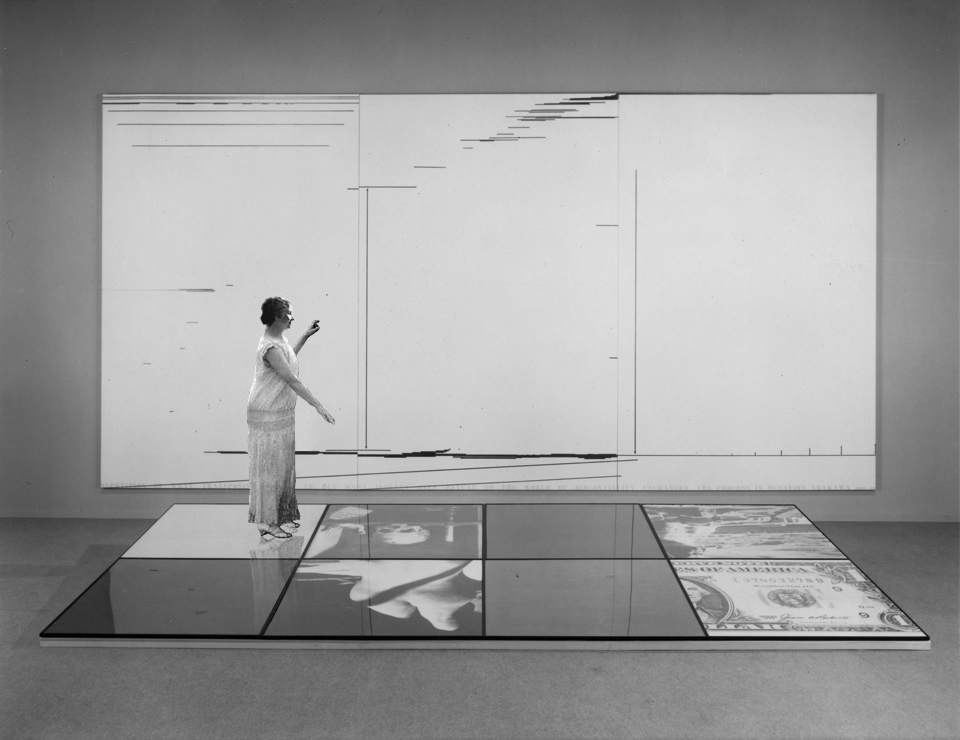

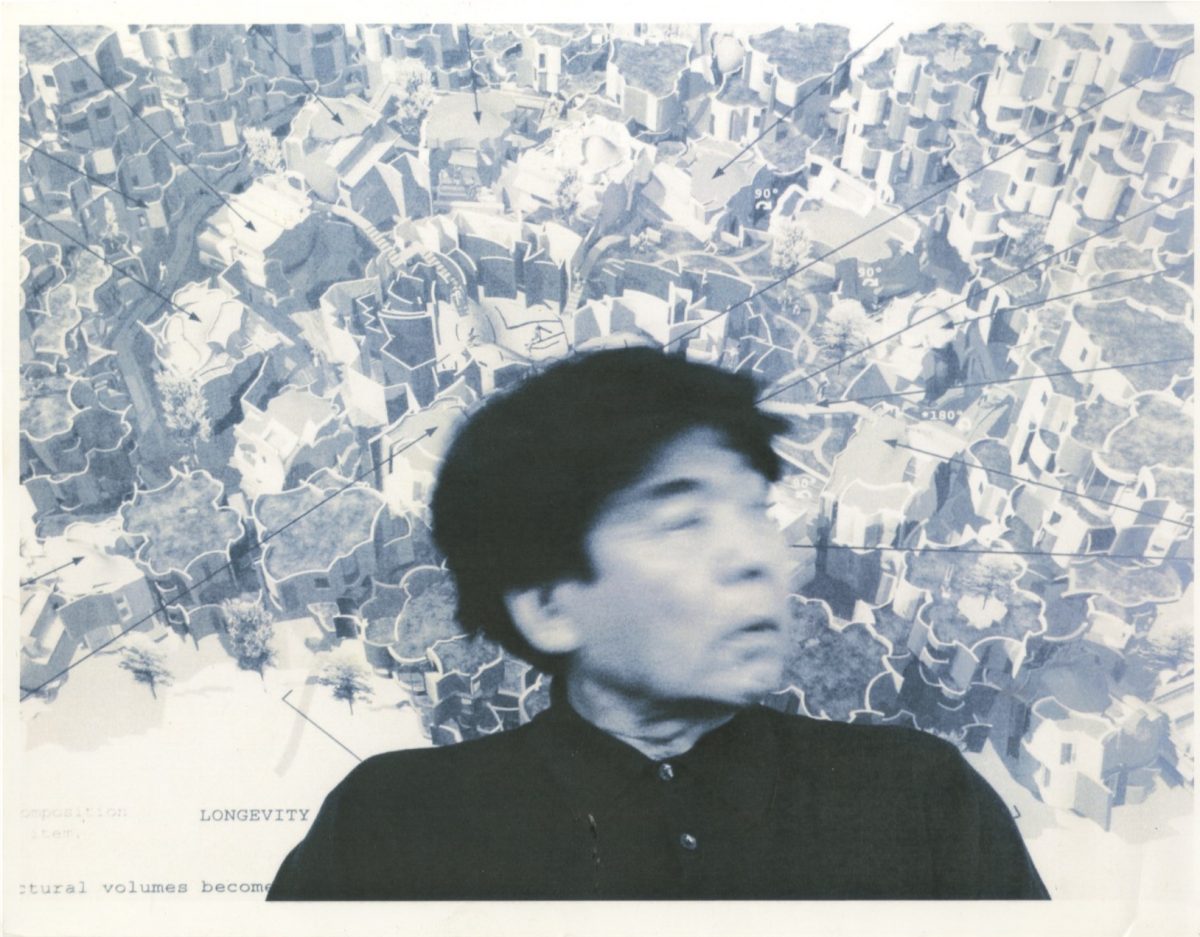

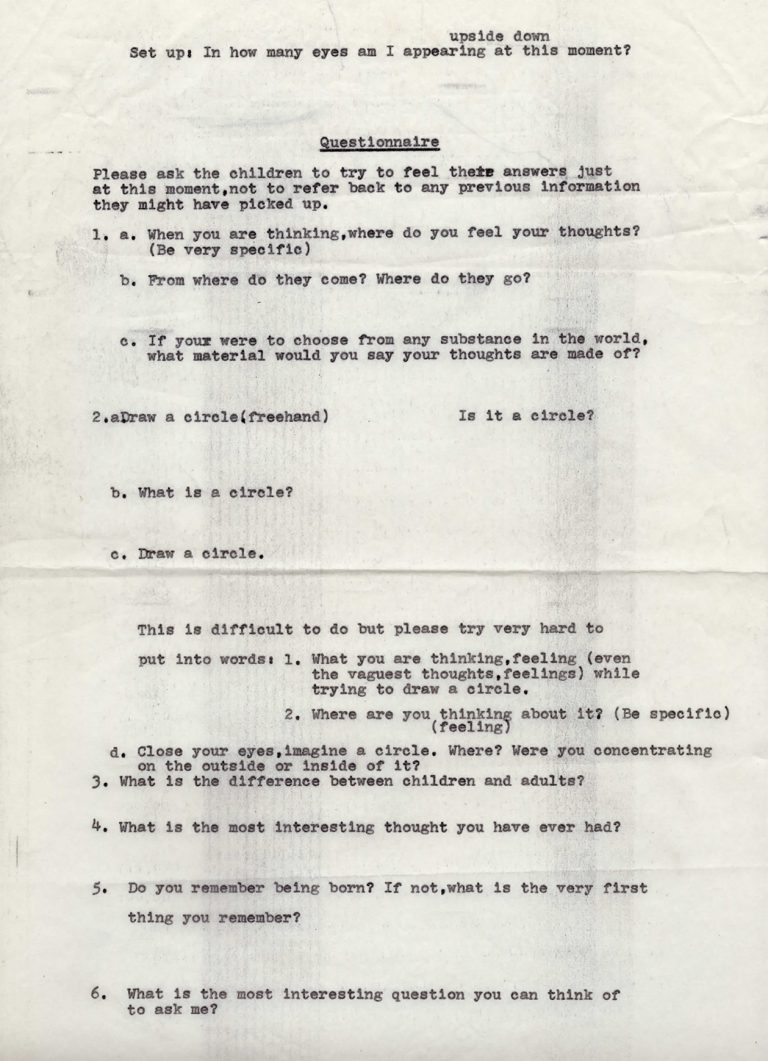

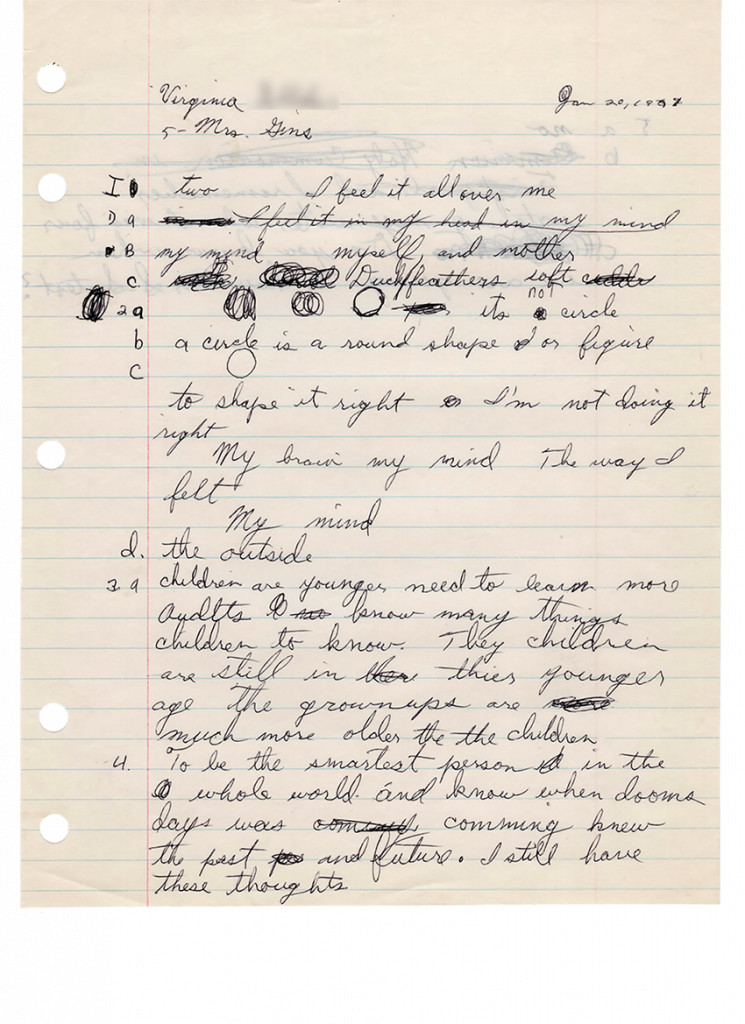

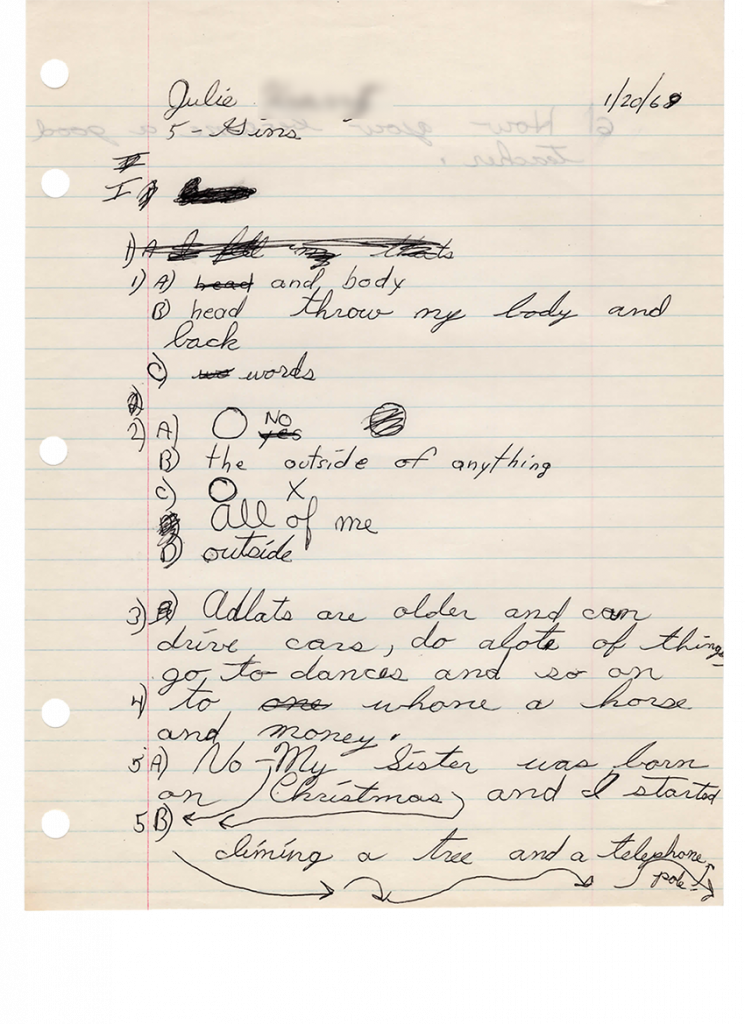

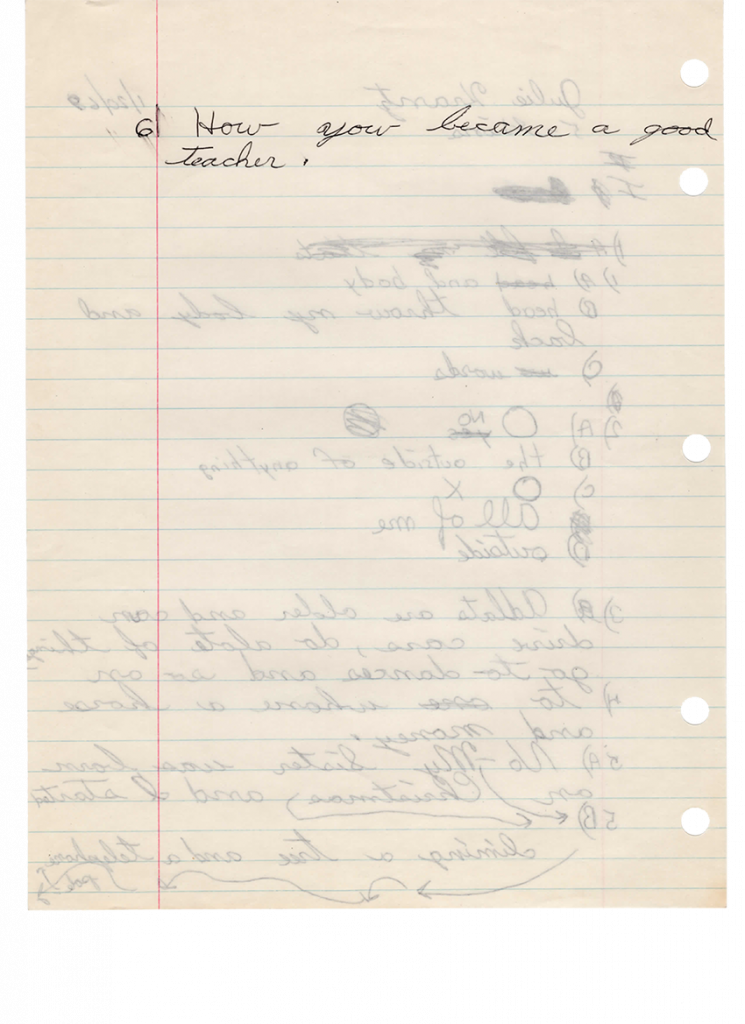

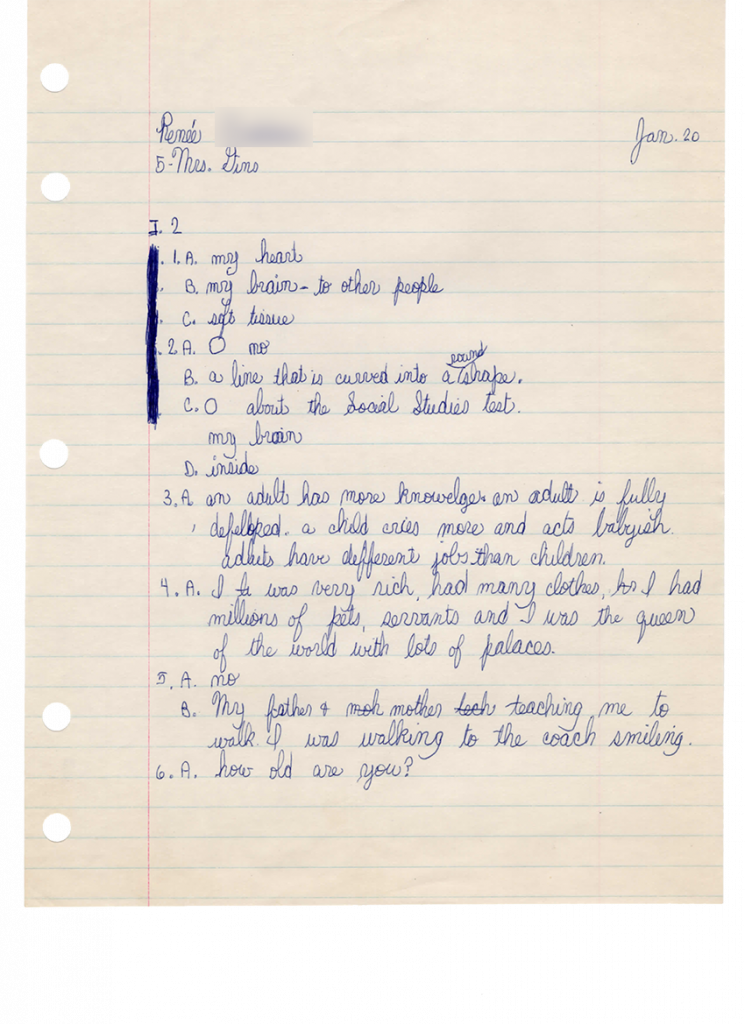

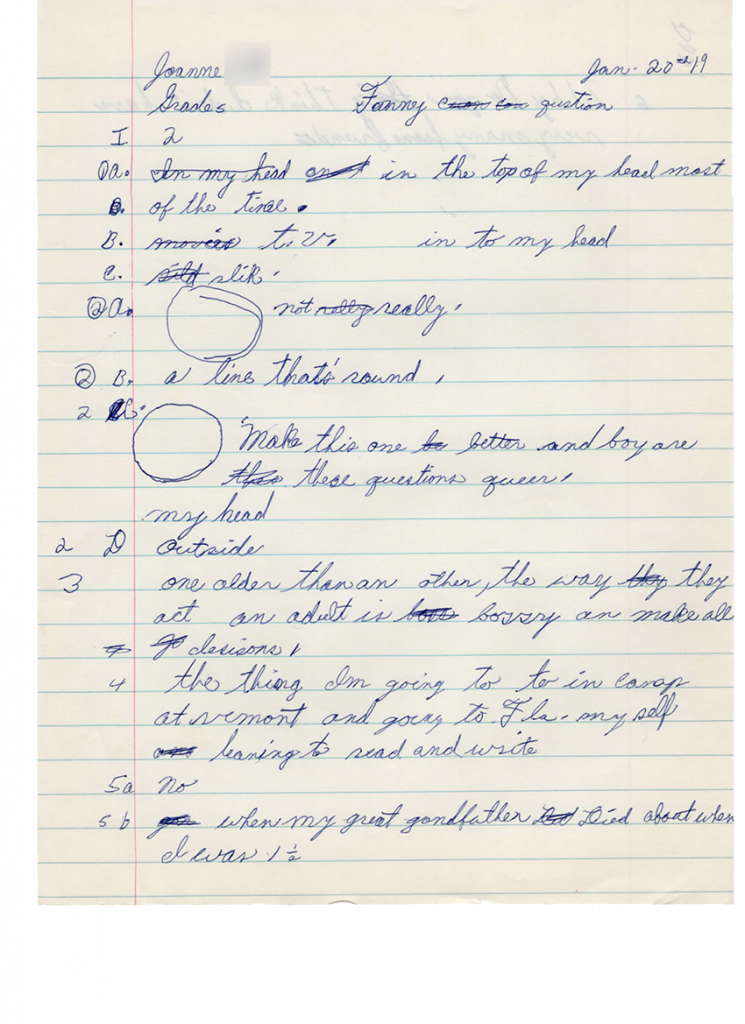

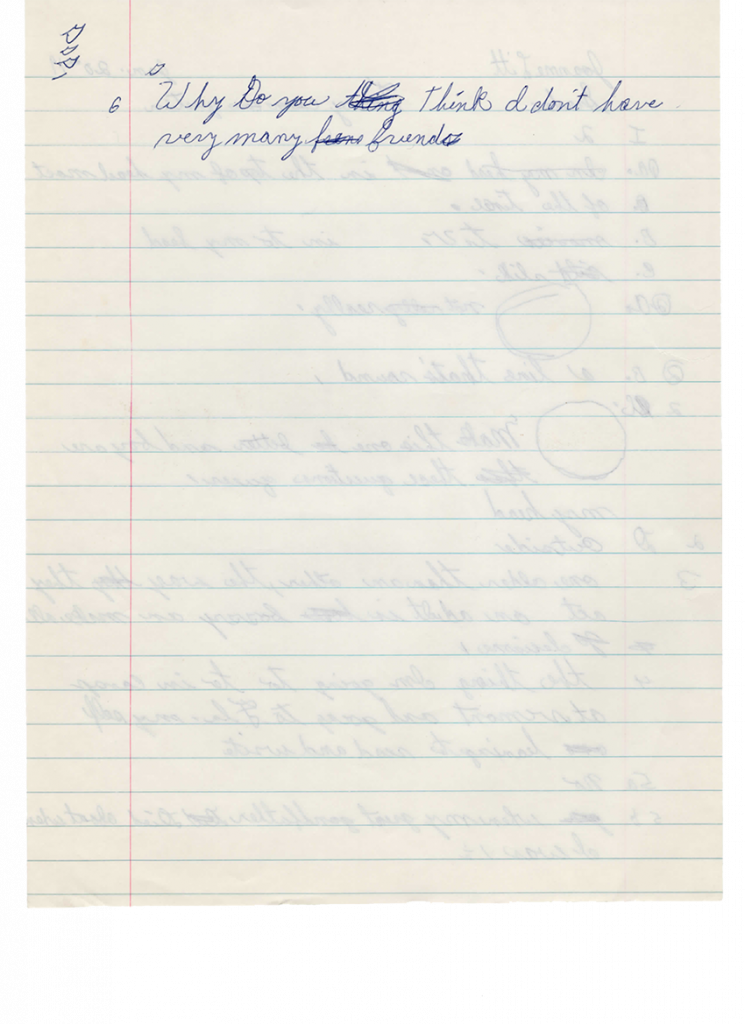

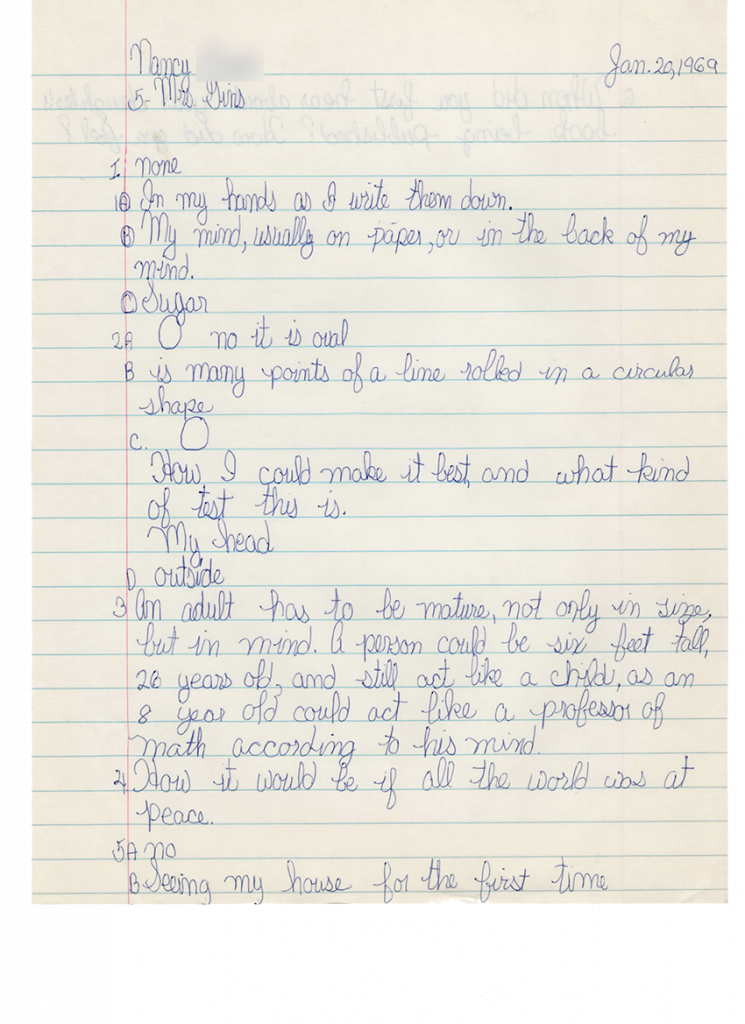

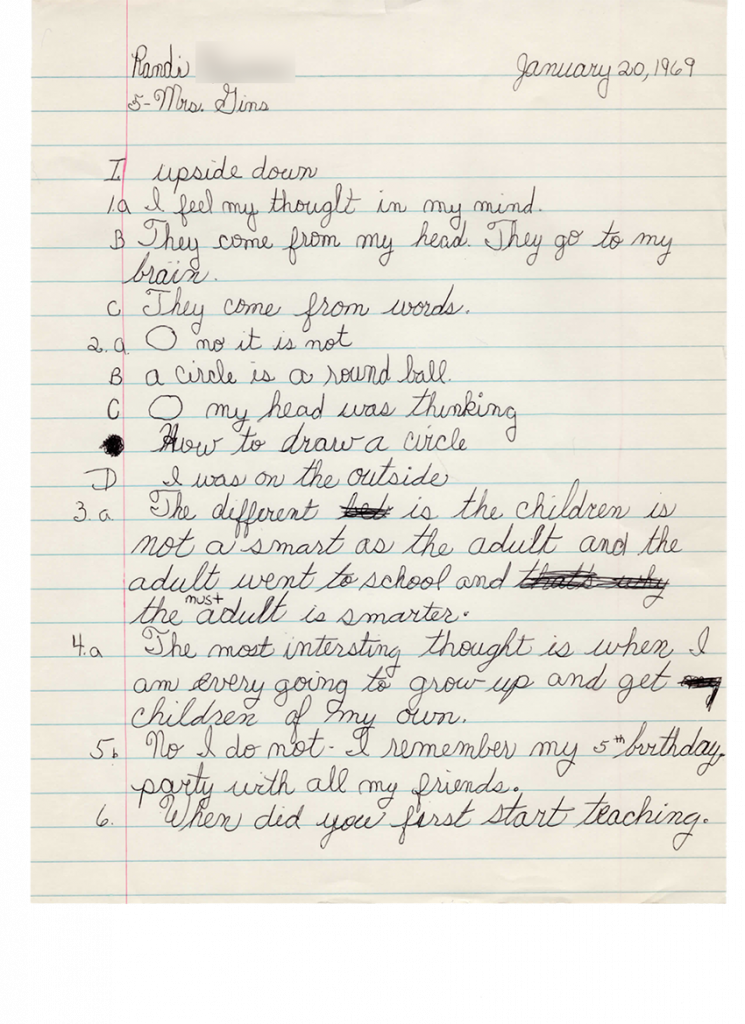

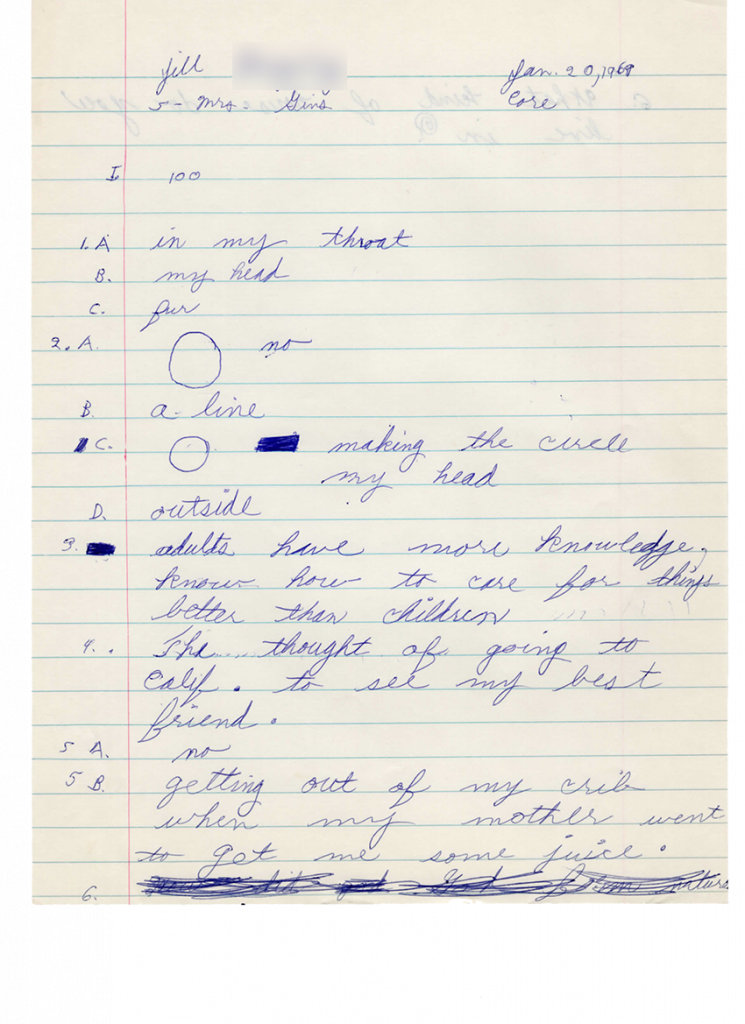

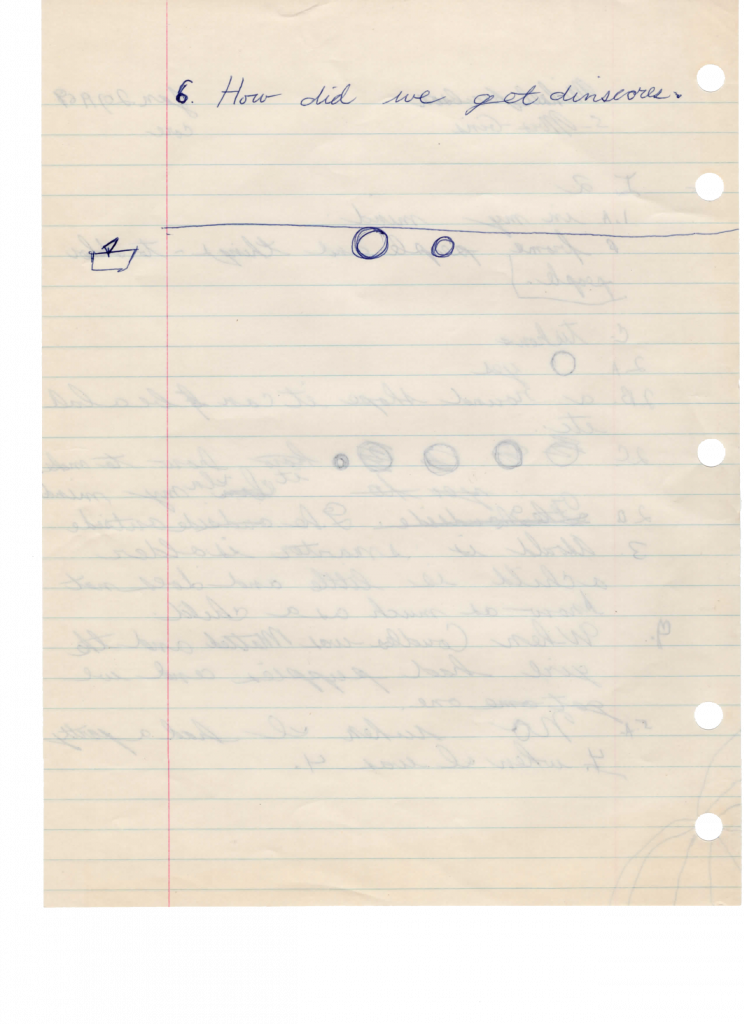

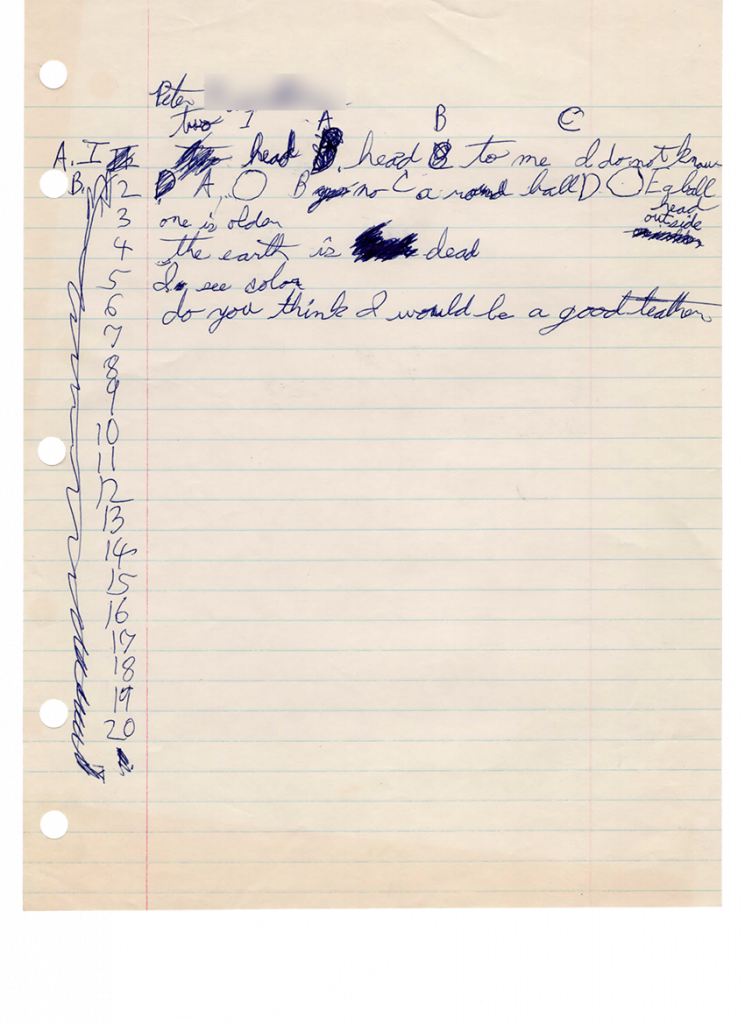

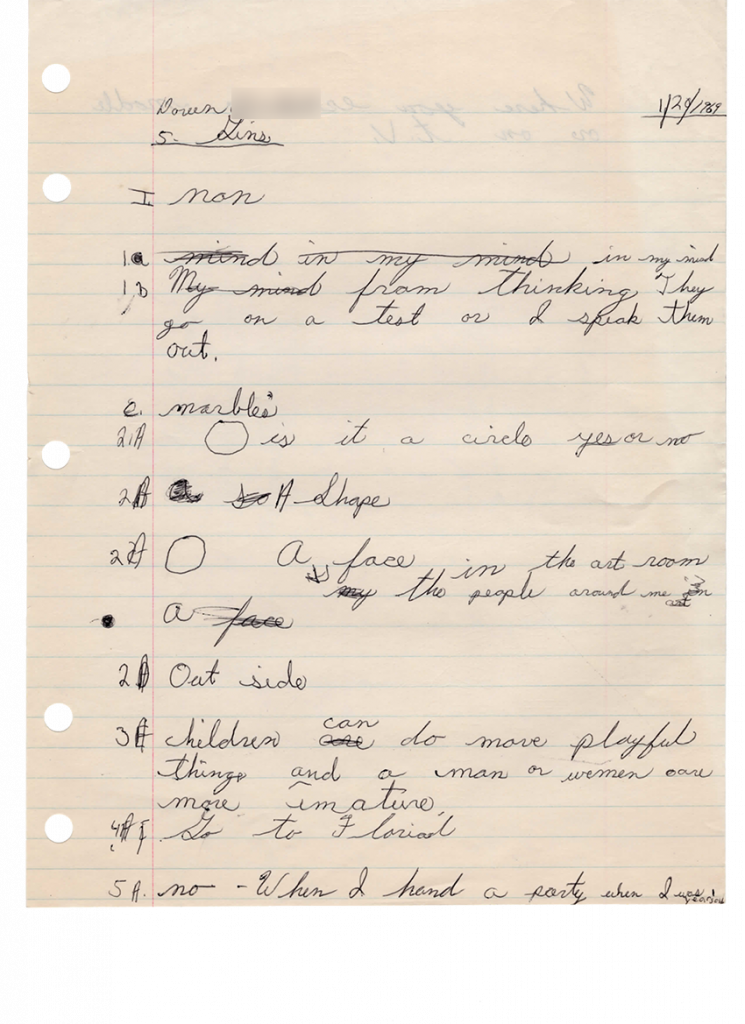

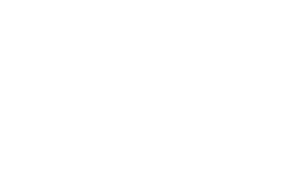

Throughout Arakawa’s career, he produced only two films, Why Not: A Serenade of Eschatological Ecology (1969; fig. 1) and For Example: A Critique of Never (1971; directed by Arakawa). Two hours and ten minutes long, Why Not features one female protagonist played by Mary Window and a narration by Madeline Gins. Shot in Arakawa and Gin’s apartment at 124 West Houston Street for the most part, the film shows the woman examining everyday objects that surround her—the table, the door, the plant, the toilet, the sofa, etc.—in a deviated manner that ignores the intended use of the objects. In the background, Toshi Ichiyanagi’s music rings out at a monotonous tempo, emphasizing the film’s structure that more closely resembles an assemblage of actions than a clear narrative. All the while, the woman is apparently obsessively haunted by a mnemonic image of a dead man, who she saw lying dead on the road with his head immersed in blood. Toward the end of the film, the music becomes less sharp and dissolves into a mumbling sound, leading into a scene in which the woman places a reversed bicycle wheel in between her legs as a tool for masturbation (fig. 2); as one may suggest, the use of a spinning bicycle wheel is an explicit reference to Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913). [1] In the next scene, the woman thrusts her body into a corner, which causes her head to bleed, and she collapses on the floor. A disembodied hand holding a stick suddenly appears from outside of the frame and says “open,” as a command directed at the woman’s closed hands. In the ending scene, a narrator says, “This is the end? Maybe not,” challenging the association of death with an end.

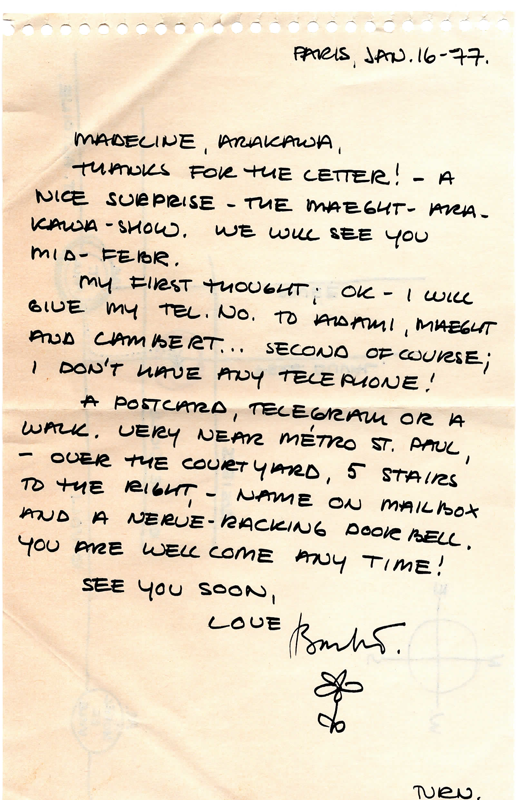

Why Not is an elusive and complex film. Its assembly of unfathomable scenes of objects used in odd manners, a mediation on eroticism induced by the motion of the bicycle wheel, and the imagery of death that opposes the idea of death as a termination of life, underscore the complexity of the film. The film is mostly known through film curator Amos Vogel’s writing in the acclaimed publication Film as a Subversive Art (1974), published four years after Why Not’s screening at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1970.[2] However, it was when the film screened at the Sogetsu Kaikan Hall, Tokyo, on November 7th, 1969, that it received the most robust critical attention. Arakawa’s sudden turn to filmmaking was unexpected to the Japanese audience and the reaction varied on how to interpret this film.[3] Art critic Junzo Ishiko, who had written widely on topics ranging from art to underground culture, saw a continuity between Why Not and Arakawa’s mid-1960s paintings, while experimental filmmaker Takahiko Iimura, who was well-acquainted with Arakawa as a neighbor in New York, interpreted the film as distinct from the paintings.[4] Several other critics, such as Koichiro Ishizaki and Tasuto Oshima, also wrote in response to the screening.[5]

Why did Arakawa turn to the medium of film? How might we contextualize Why Not along with Arakawa’s earlier body of works? Ishiko’s interpretation outlines Arakawa’s interrogation of illusionism, the relation between humans and objects, and the evocation of eroticism through objects. By using his interpretation as a guide and introducing Arakawa’s own words on the filmic medium, this text will examine Why Not’s relationship to Arakawa’s paintings and seek an answer as to why Arakawa chose film as his medium for Why Not.

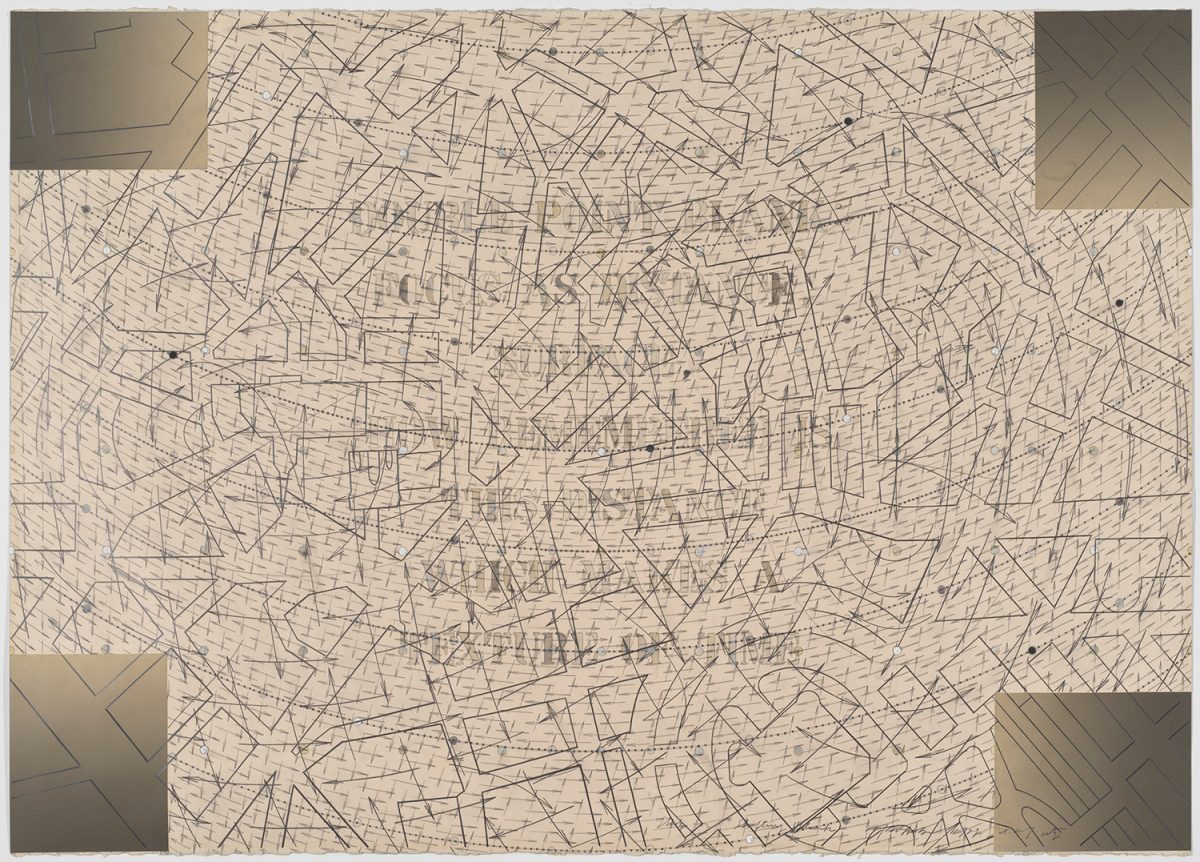

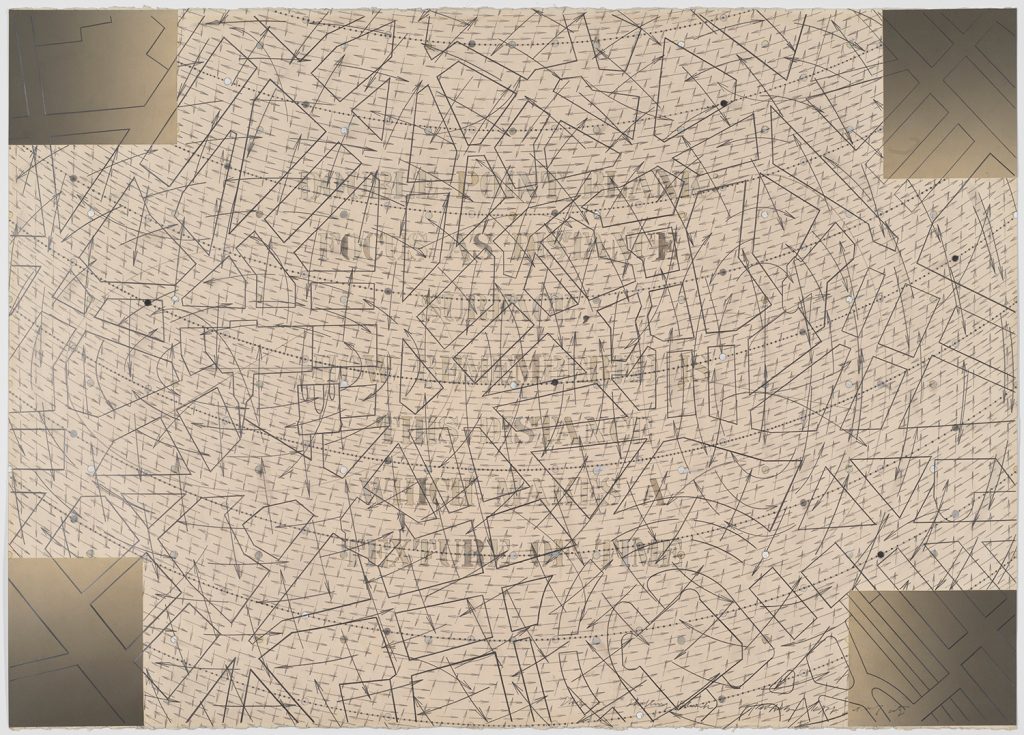

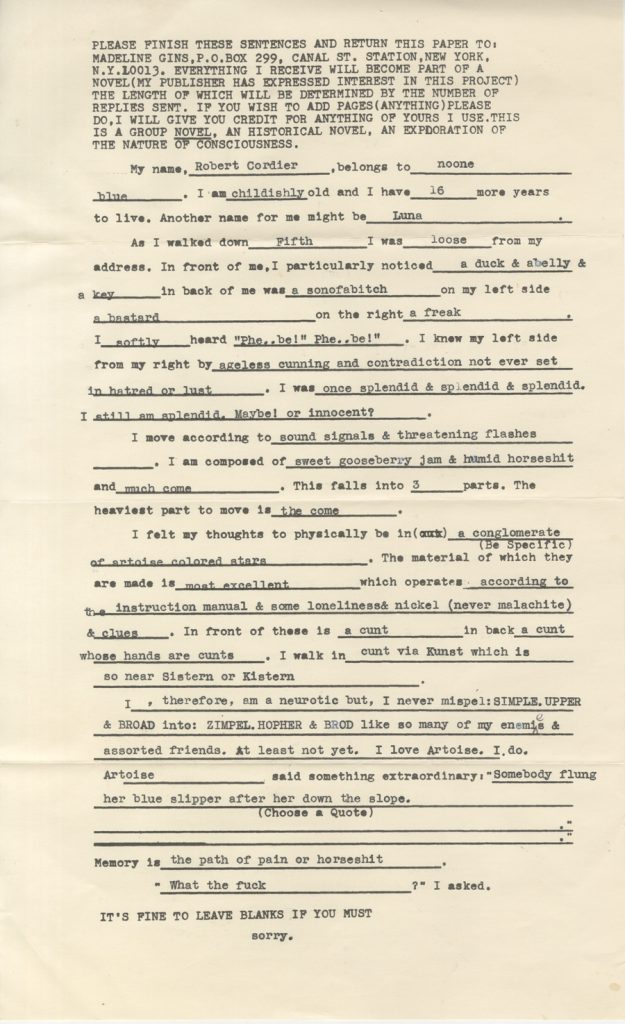

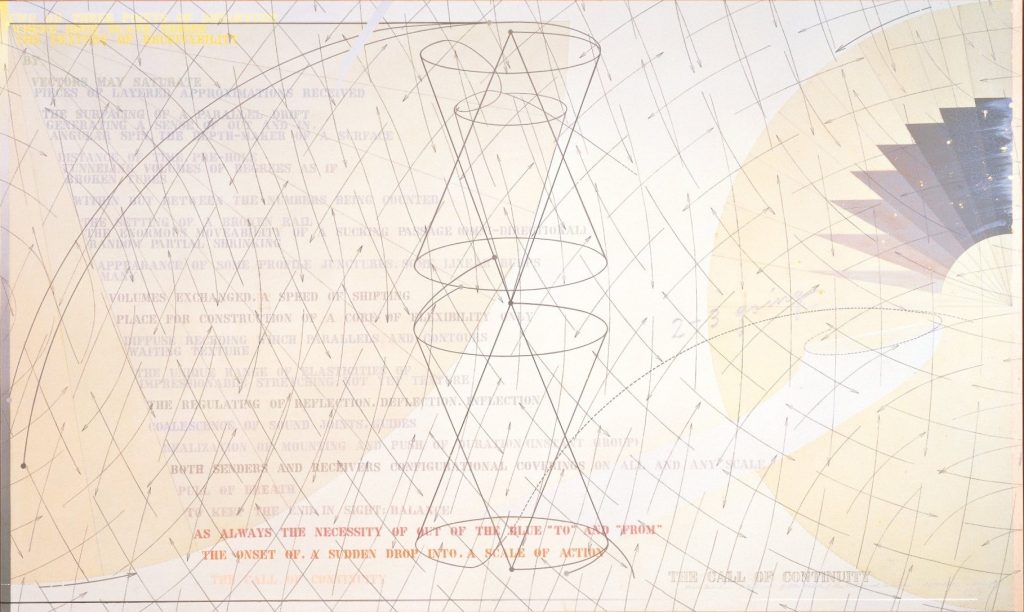

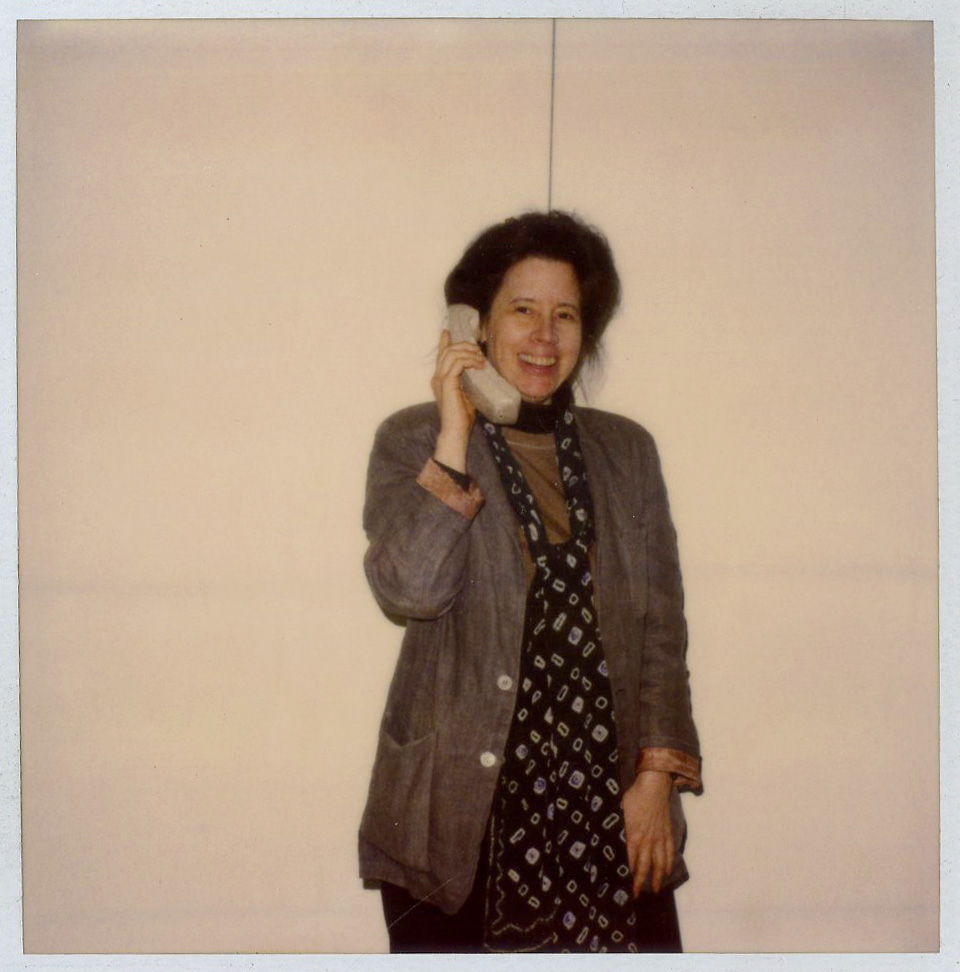

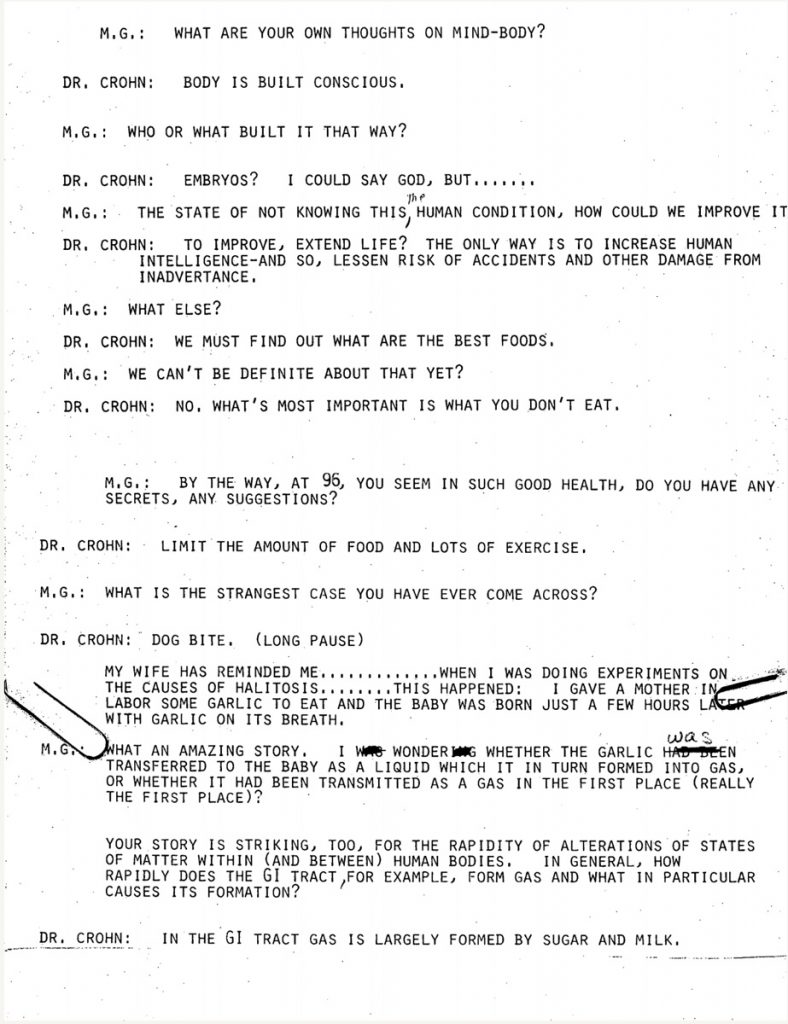

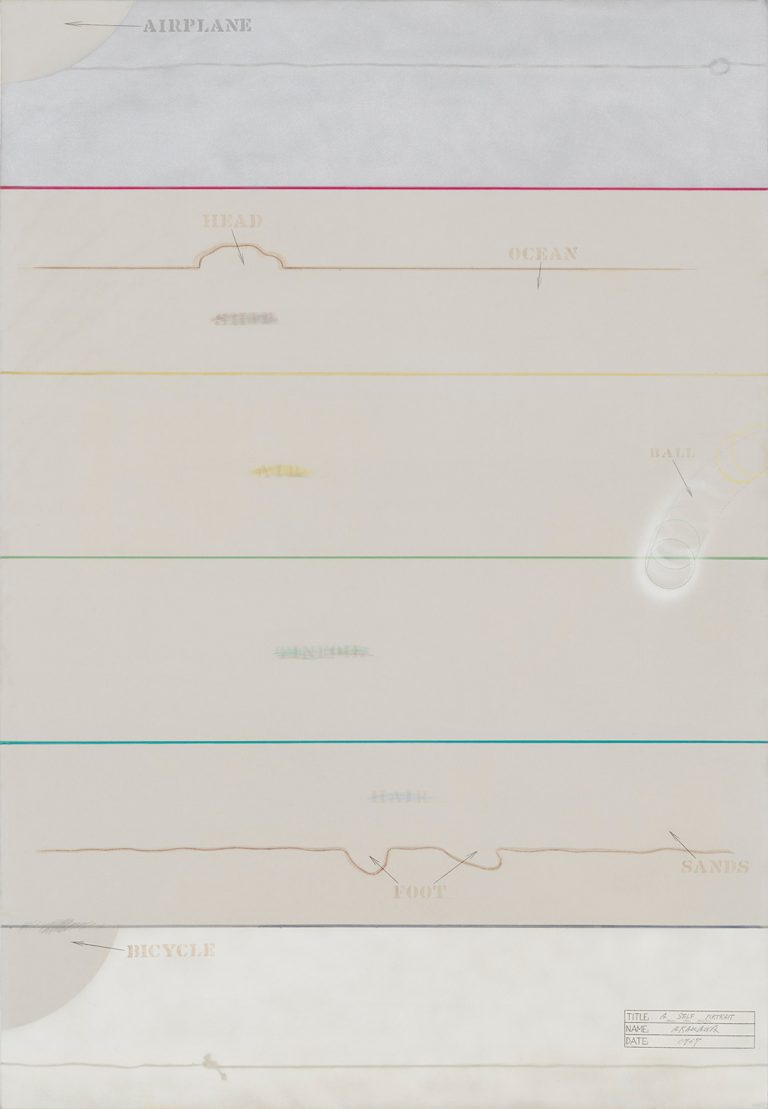

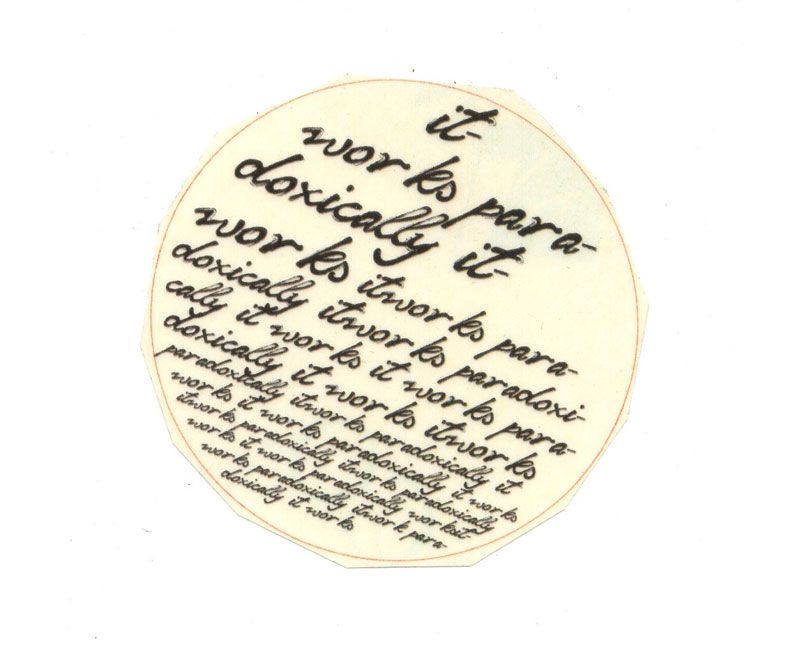

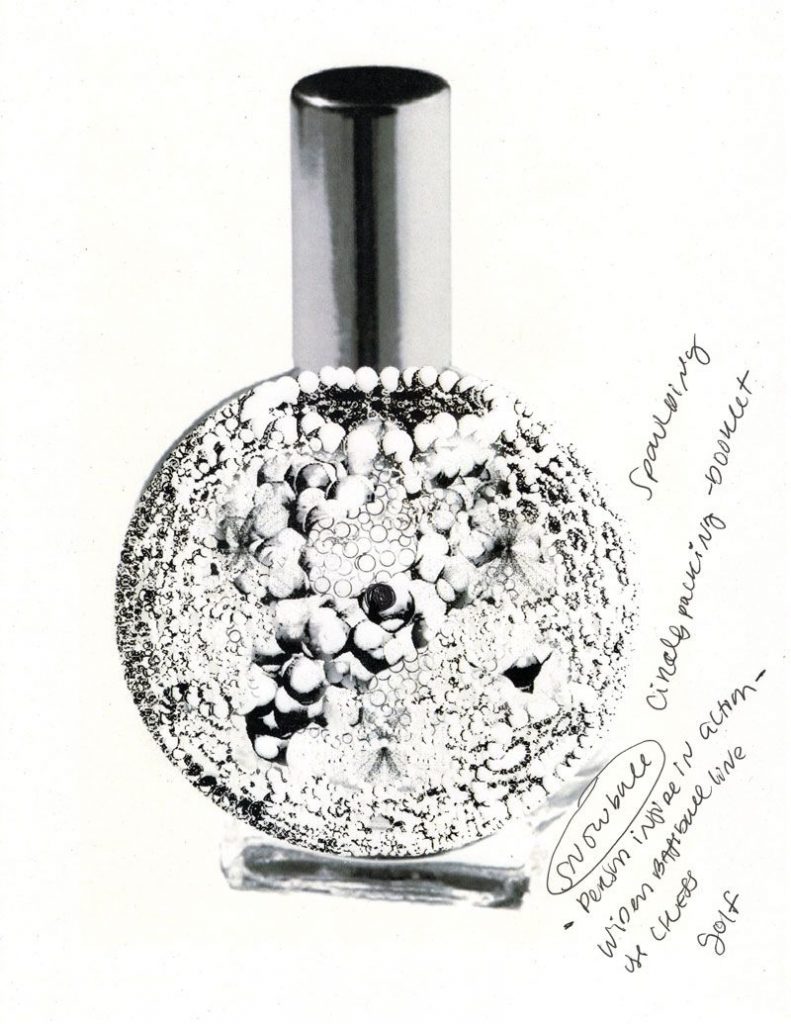

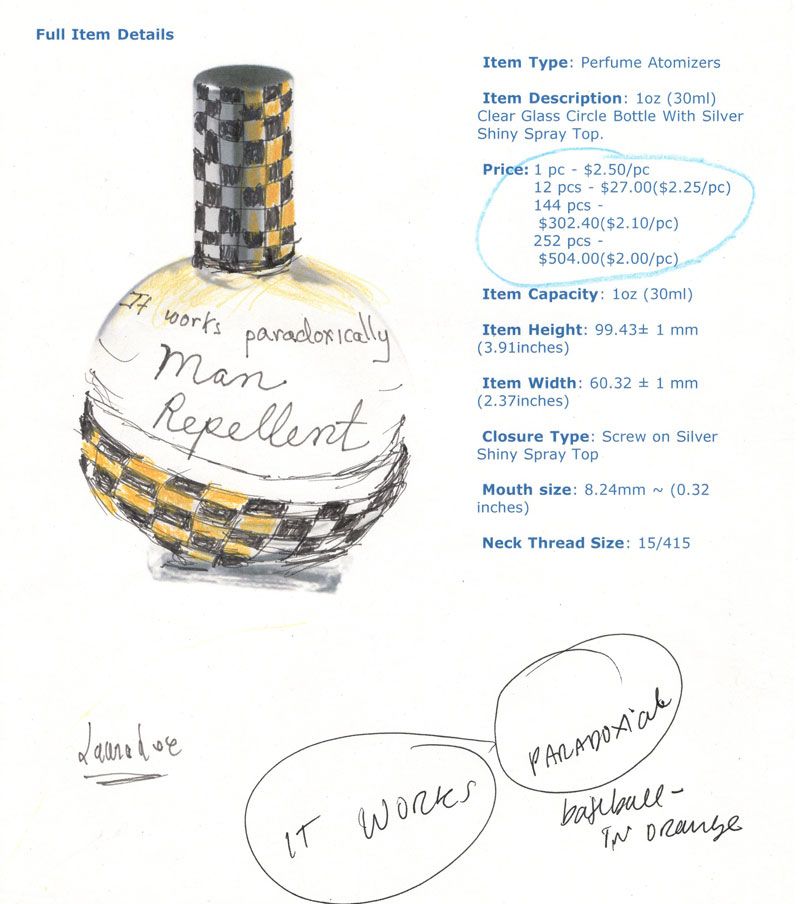

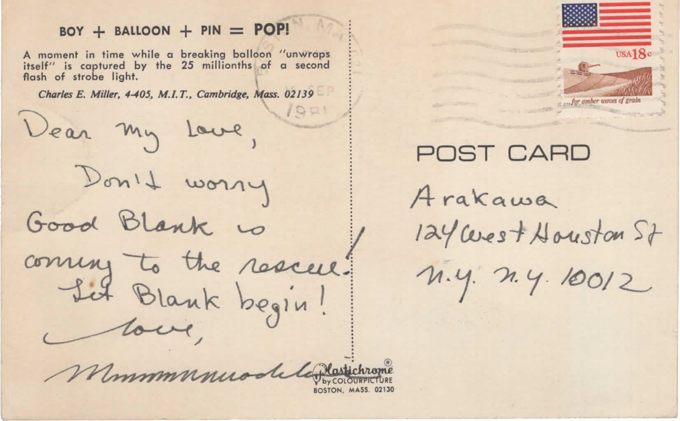

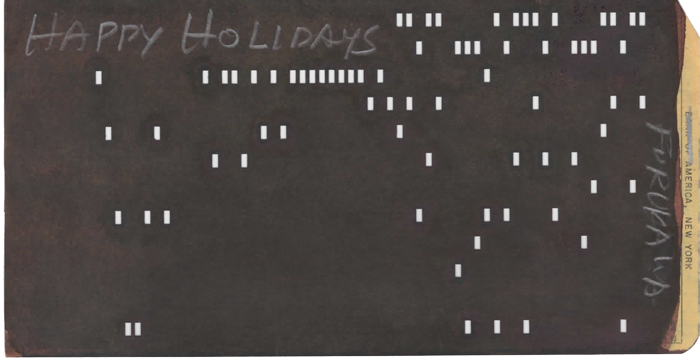

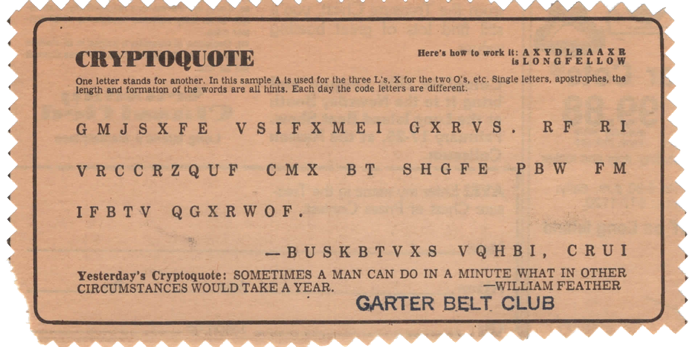

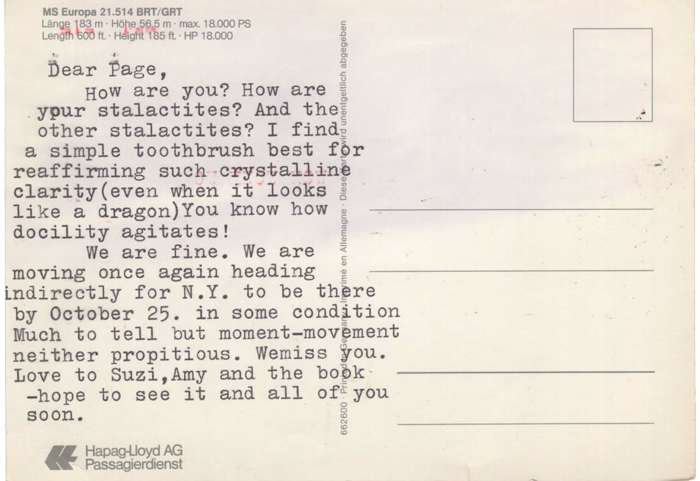

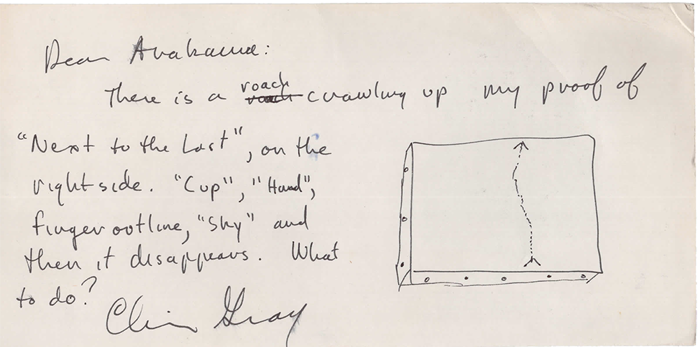

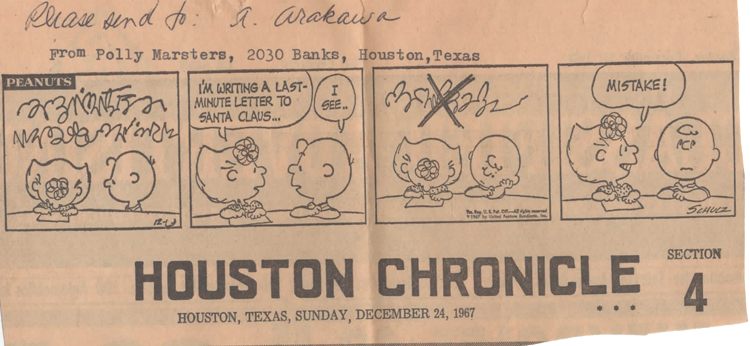

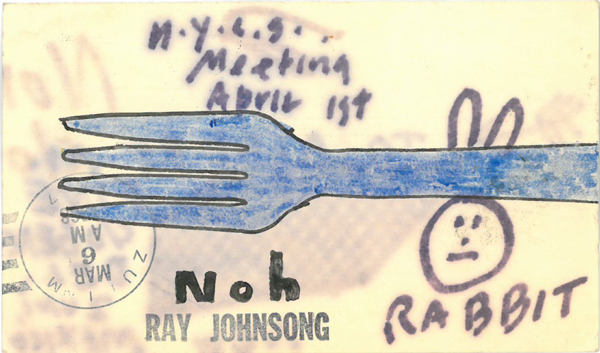

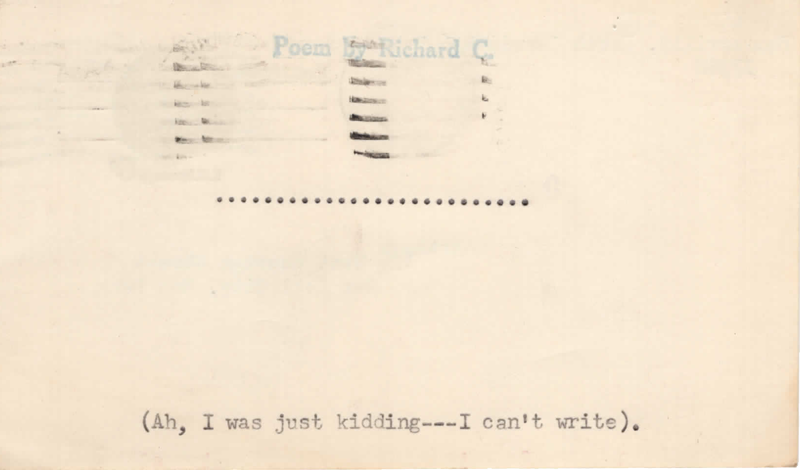

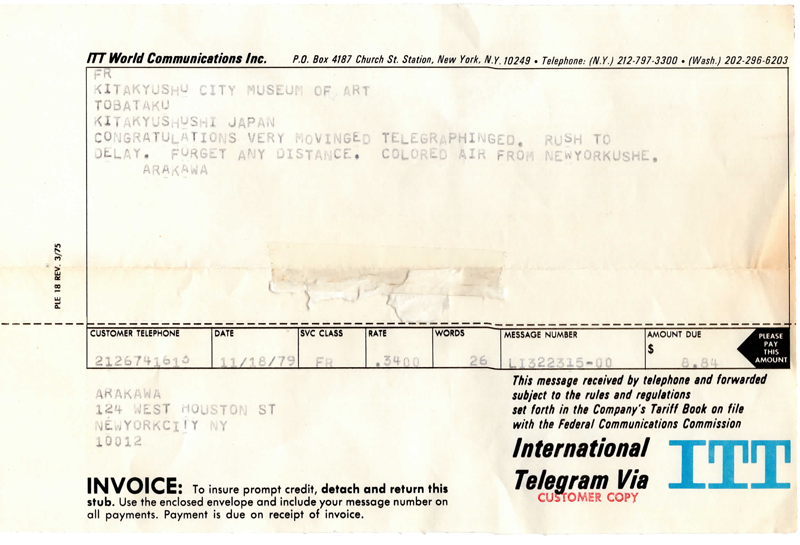

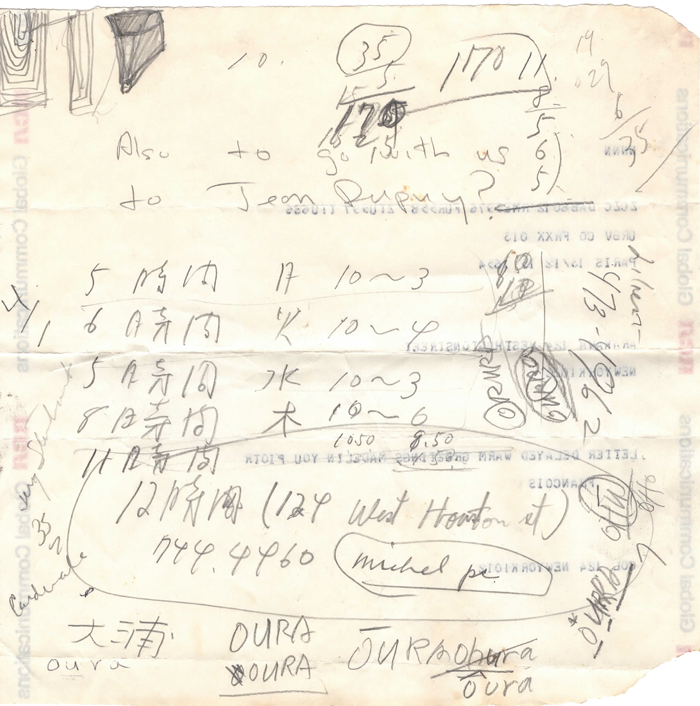

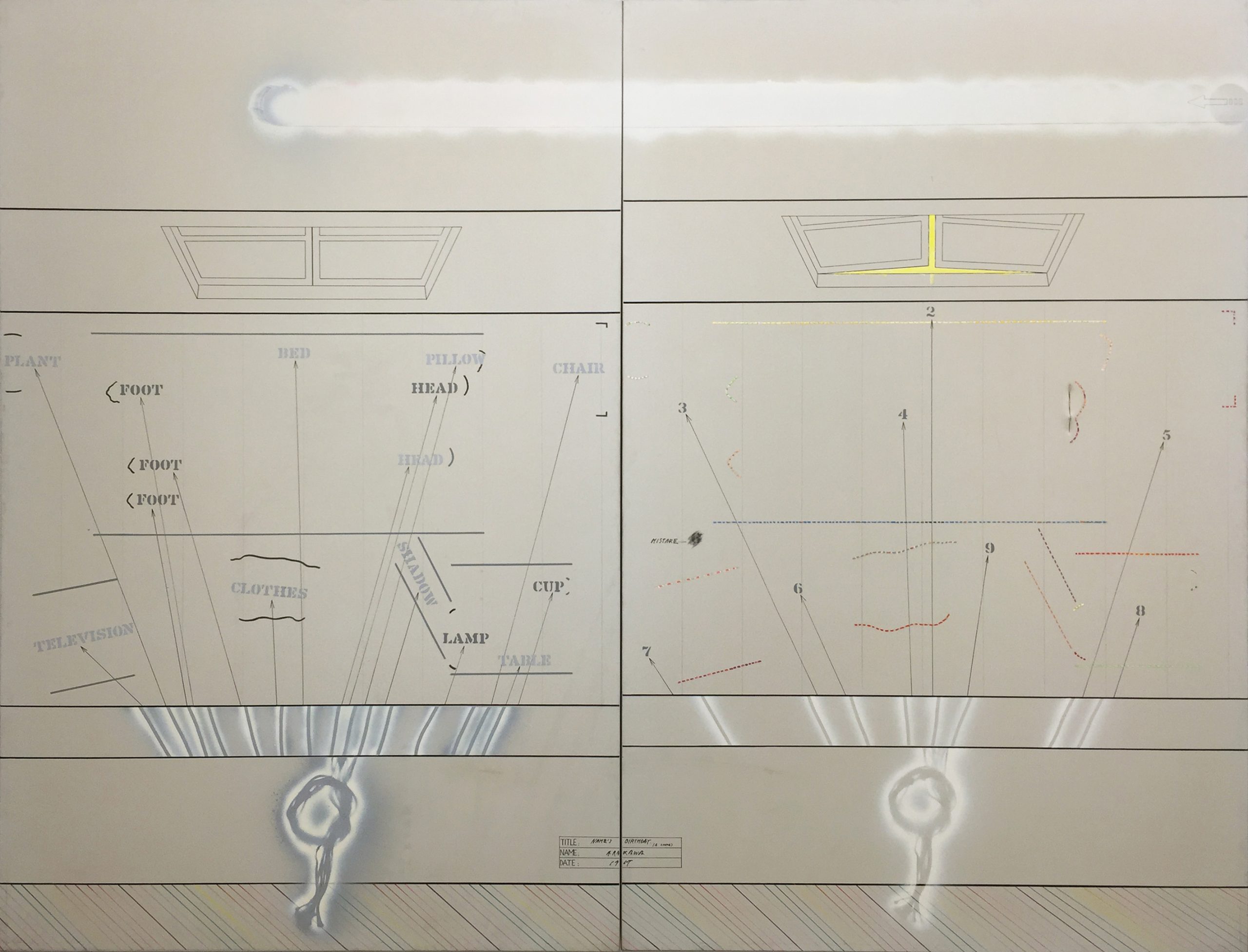

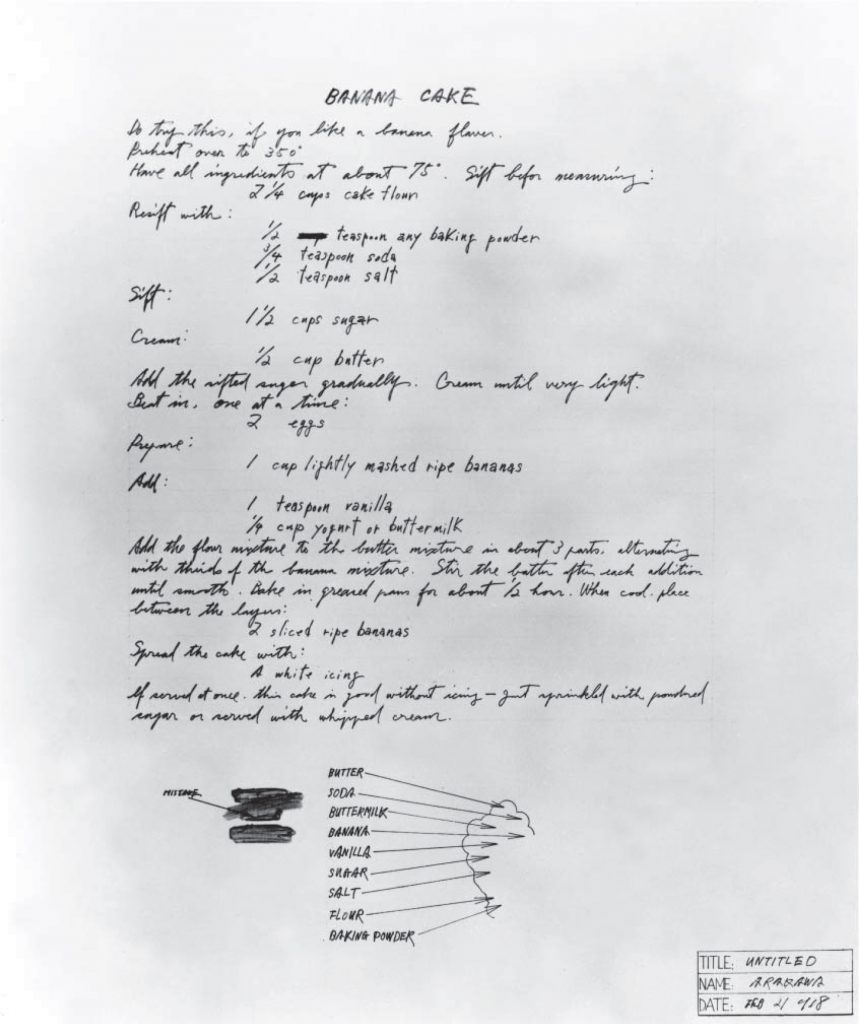

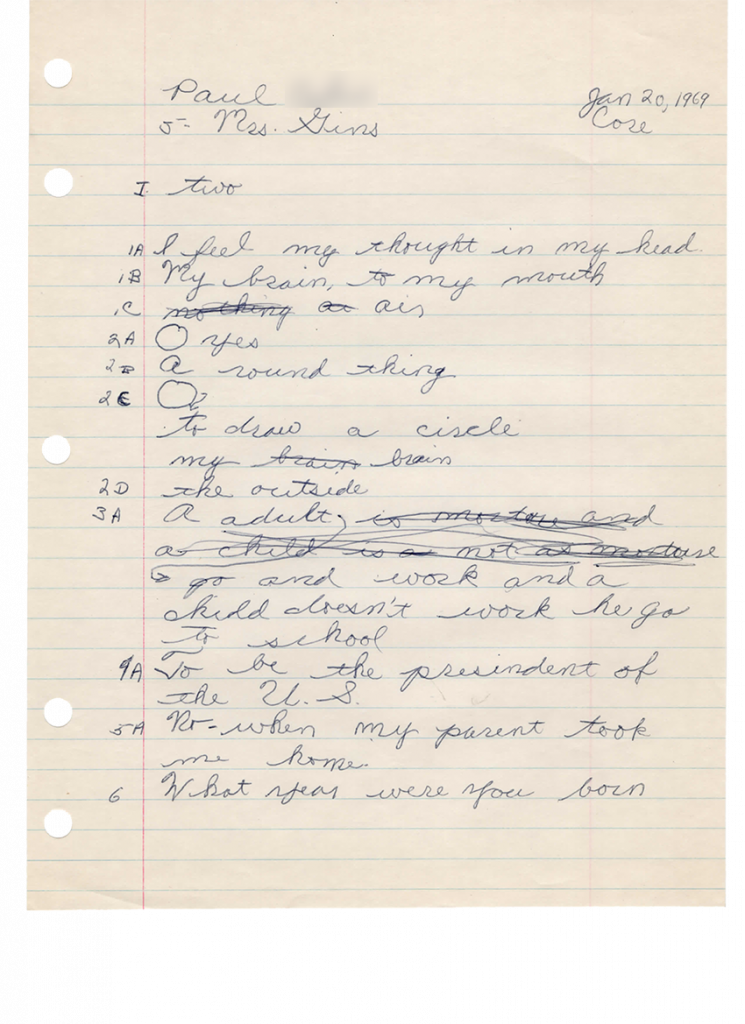

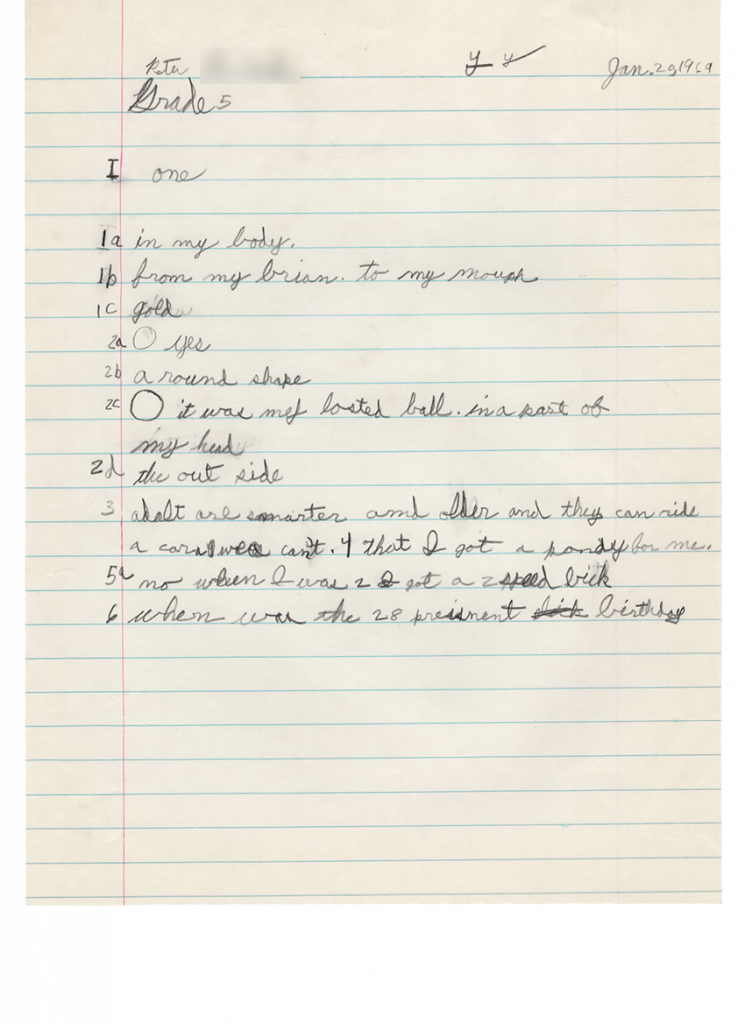

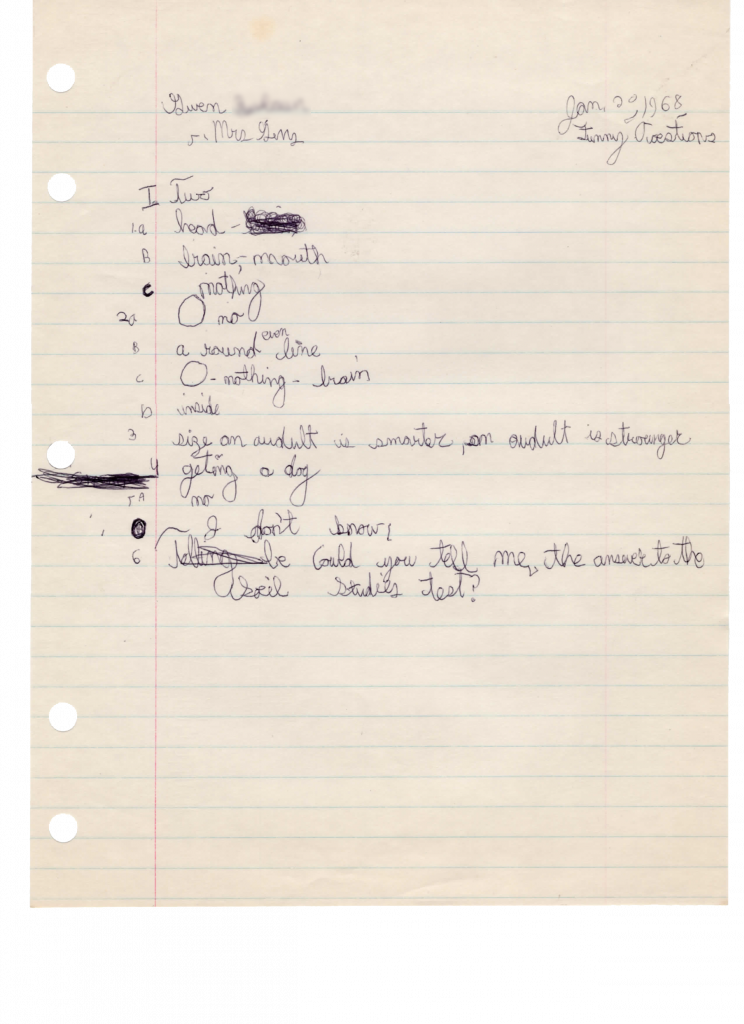

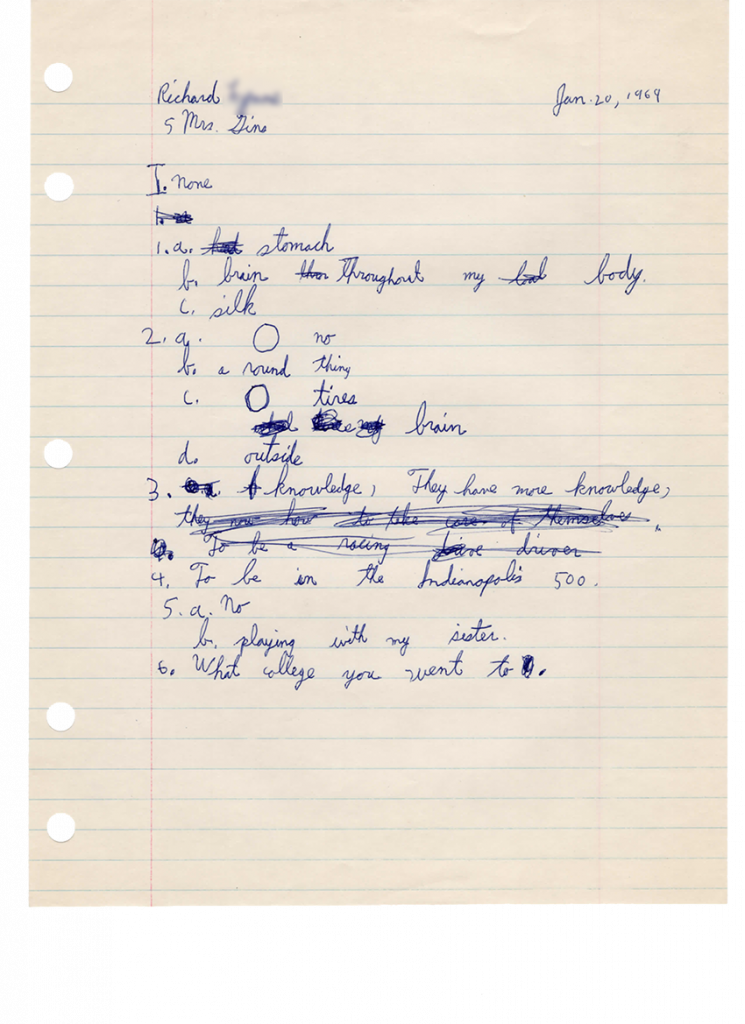

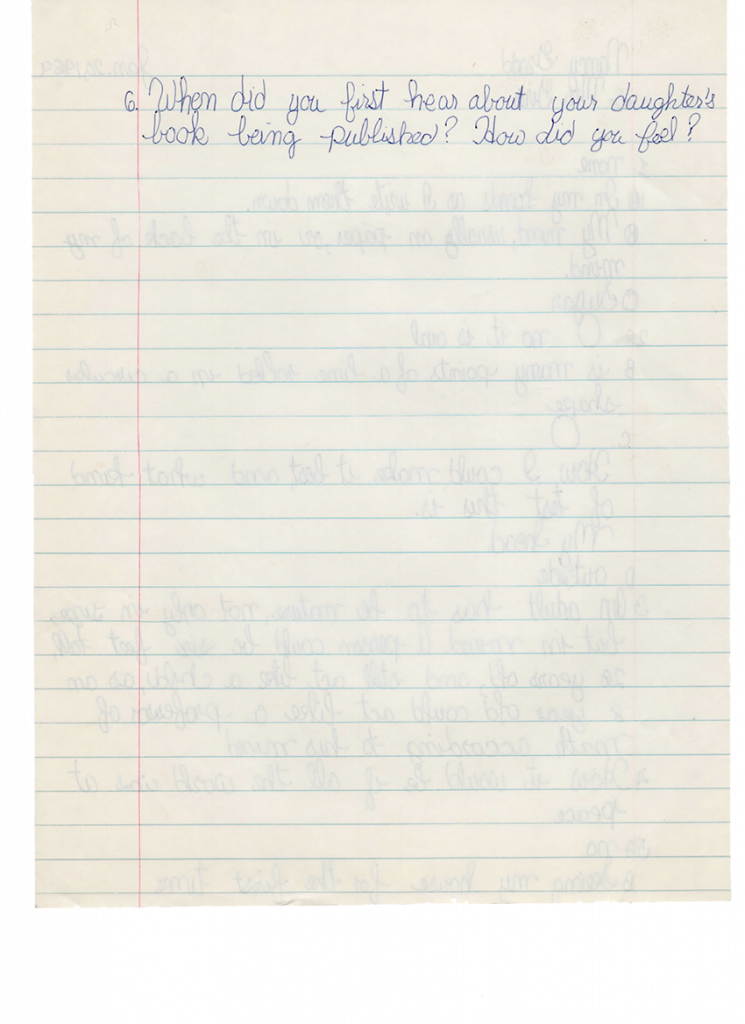

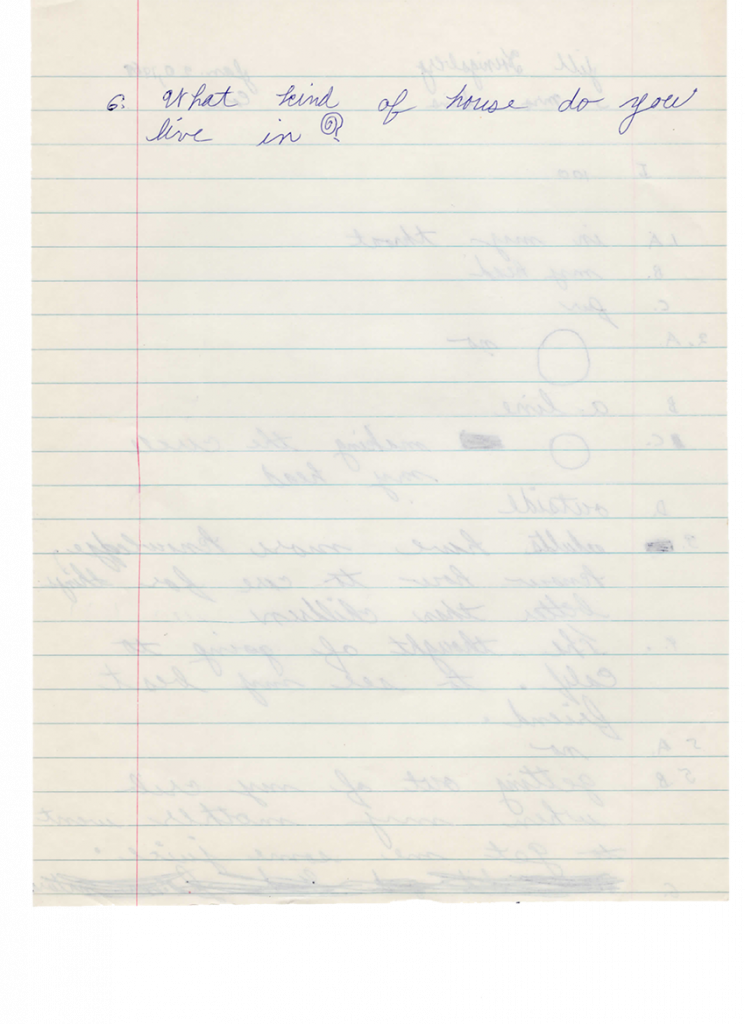

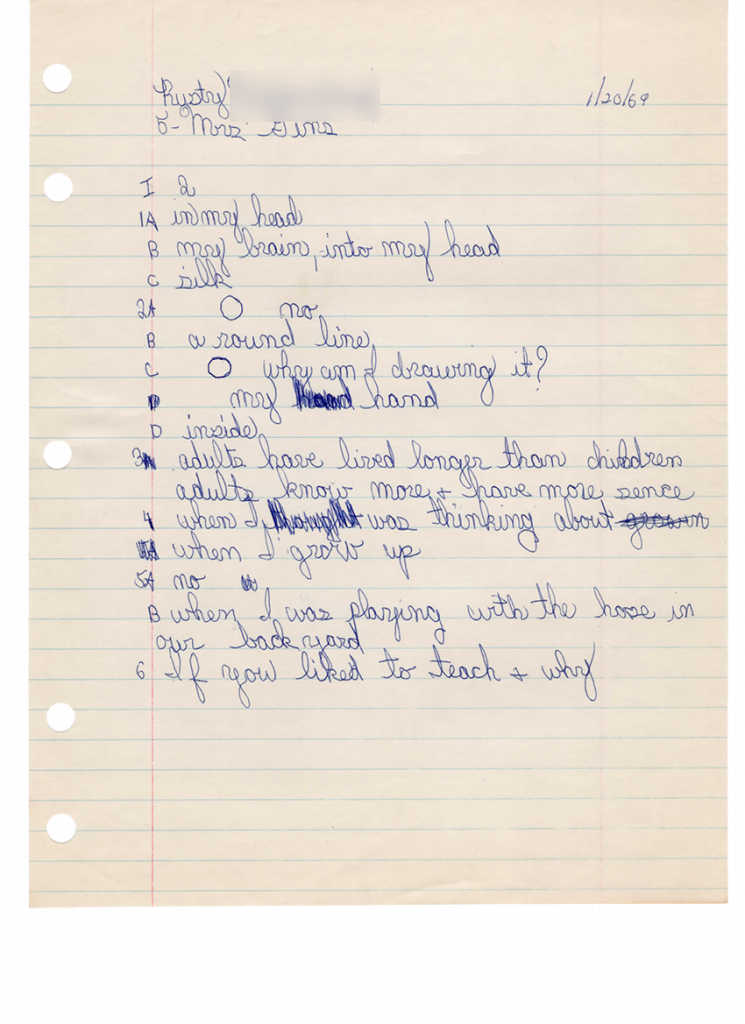

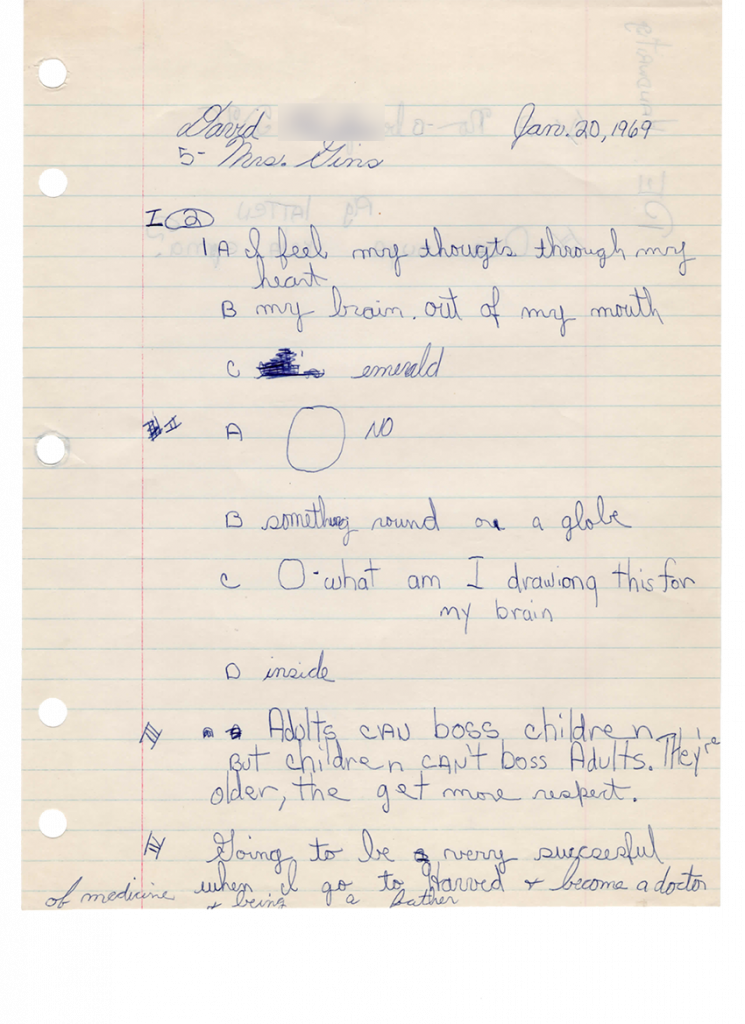

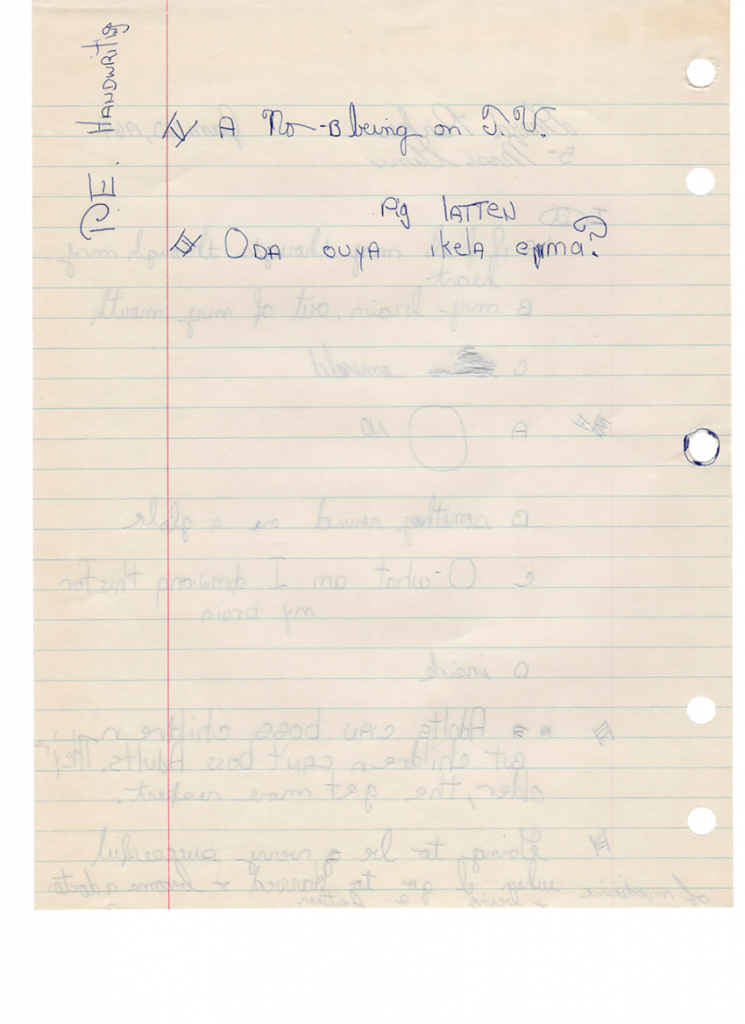

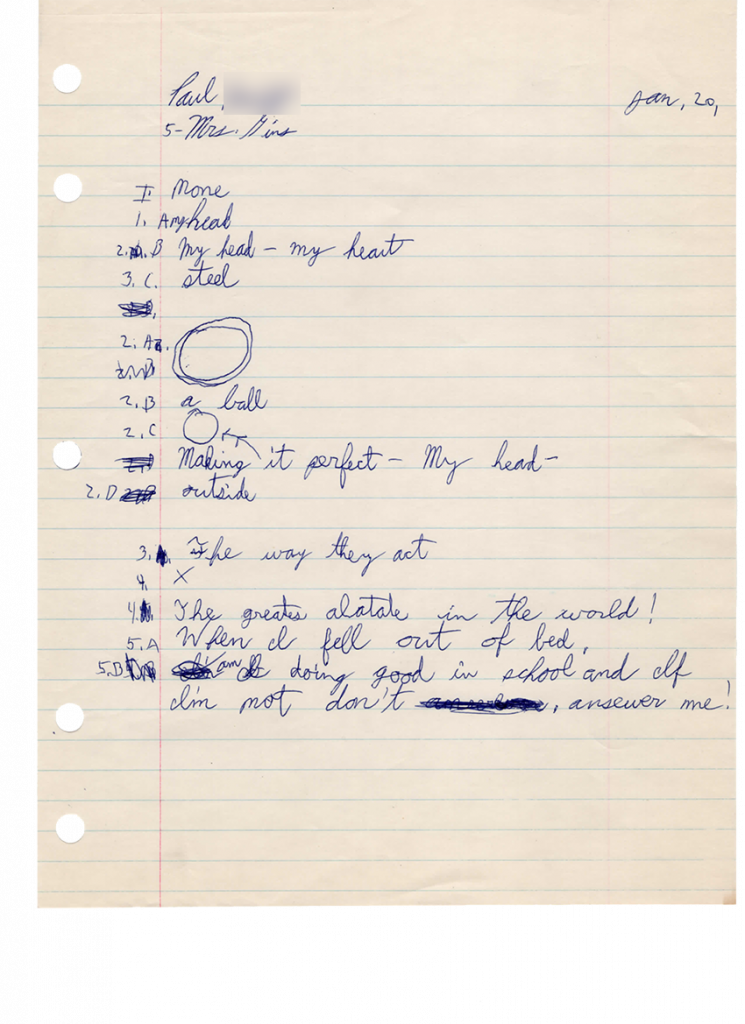

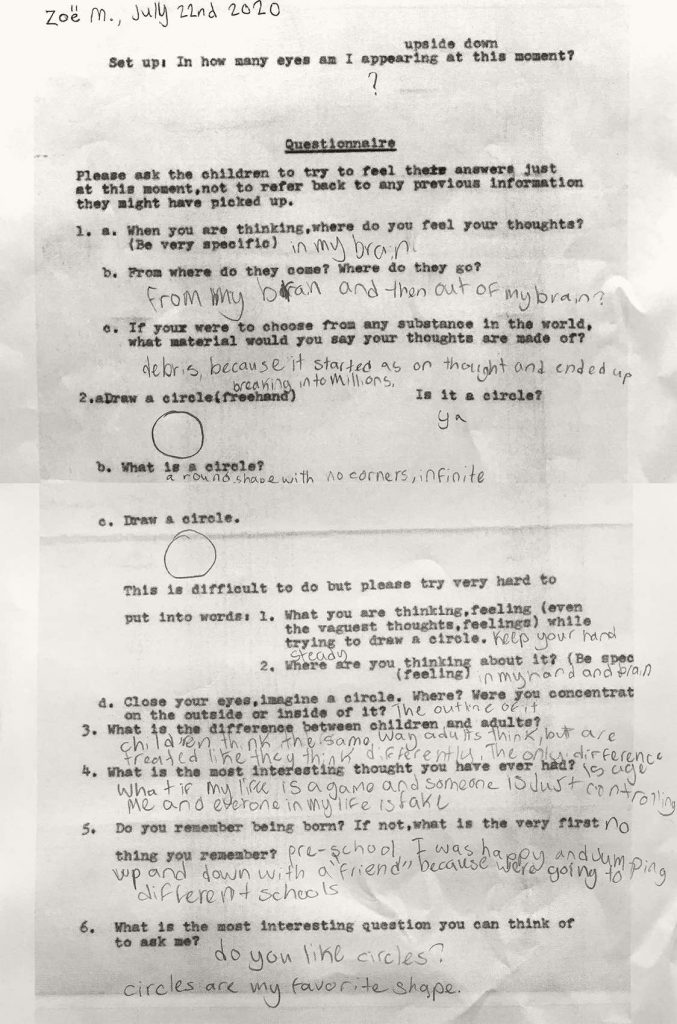

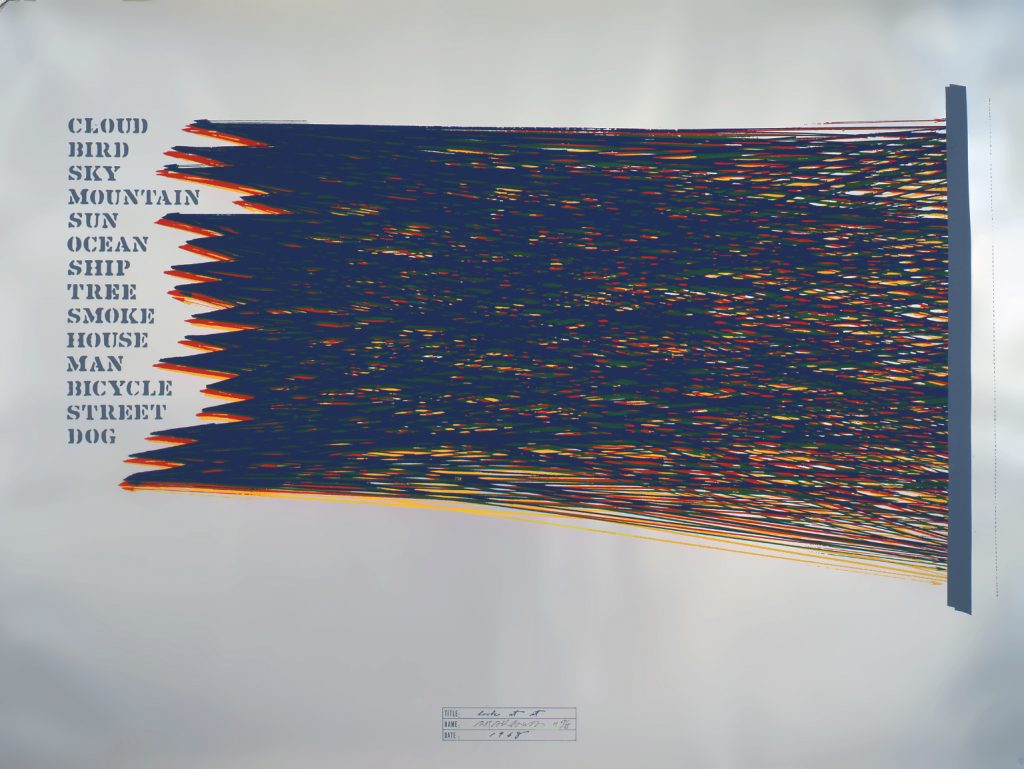

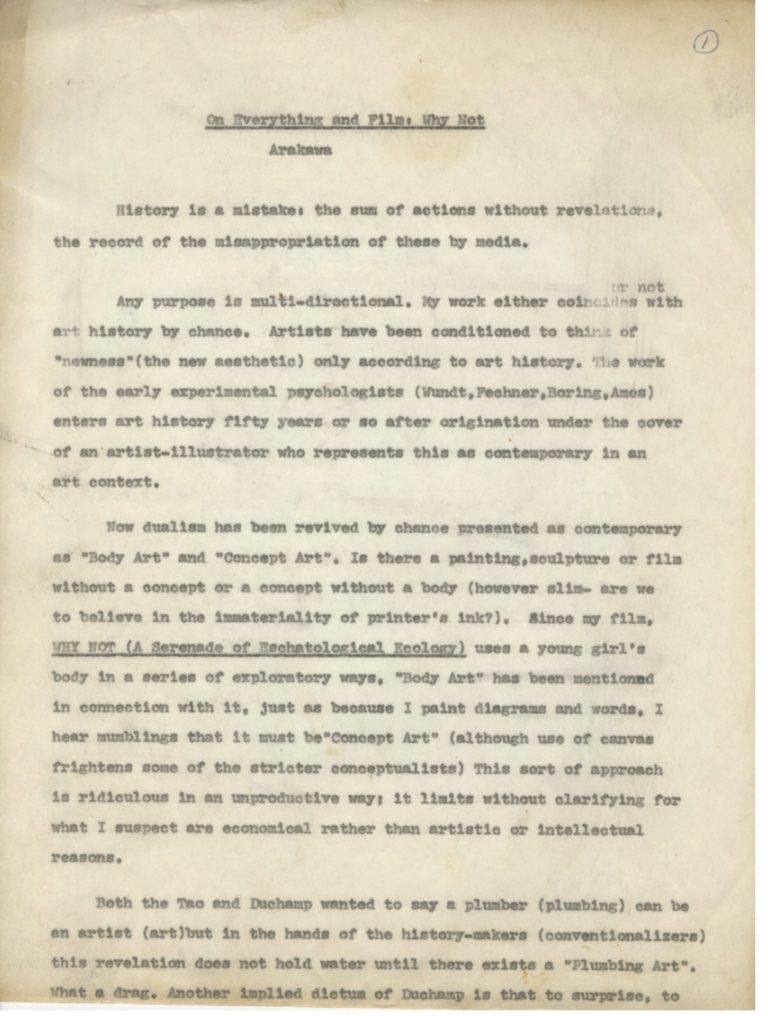

On the occasion of creating Why Not, Arakawa wrote an unpublished manuscript titled “On Everything and Film: Why Not” (fig. 3). In the beginning, Arakawa states: “History is a mistake; the sum of actions without revelations, the record of the misappropriation of these by media.”[6] For Arakawa, art was one of the ways to reveal the “mistake” of history. Refusing to identify the film with the concurrent art trends in the late 1960s such as conceptual art, Arakawa explicitly wrote that his usage of film was in tandem with the development of “categories,” or subdivisions, in his ongoing painting series The Mechanism of Meaning (a collaboration with Madeline Gins).[7] The following excerpt from the manuscript indicates that Why Not, as well as The Mechanism of Meaning, was based upon the idea of illusion as a “mistake”:

I use film as one of many means for developing these categories, not as a move away from painting, sculpture or writing, but as a complementary medium for working of ideas. Discussions of how to escape the illusion of pictorial space are childish at best; the problem is to understand the functioning of illusionism or non-illusionistic representation to work with controlled illusion to uncover explanations rather than to avoid or despise these through ignorance.[8]

Here, Arakawa importantly notes that the interrogation of illusionism is foundational to his creation of Why Not, which is inseparable from his painting practices of the 1960s. Illusionism, in Arakawa’s sense, is a visual system that directs a relationality in a predetermined way. What Arakawa explored both in film and painting was to debunk such mandated visual system called illusionism.

Similar to Arakawa’s doubt on the system of illusionism, Ishiko’s interpretation of Why Not mirrors Arakawa’s explanation of his use of film as a way to revolt against the system of illusionism. In the following excerpt, Ishiko calls illusionism’s falsity as “fiction (kyoko)” and elaborates its significance in terms of the relationship between the human and objects:

Similar to the moment when the thick barrier of a glass disappears from our perception, while you feel the tropical fish inside the aquarium is “beautiful,” the “fiction” that determines the relationship between object and human withdraws in the live filmed-moving image. Not that the moving image tries to narrate such an issue, but that the experience of “viewing” a two hour and ten minutes live filmed-moving image, becomes the process of dissolving the “fiction.” And then suddenly, the boundless field where humans and objects are able to equivalently cross each other, appears as the act of “seeing” itself. [9]

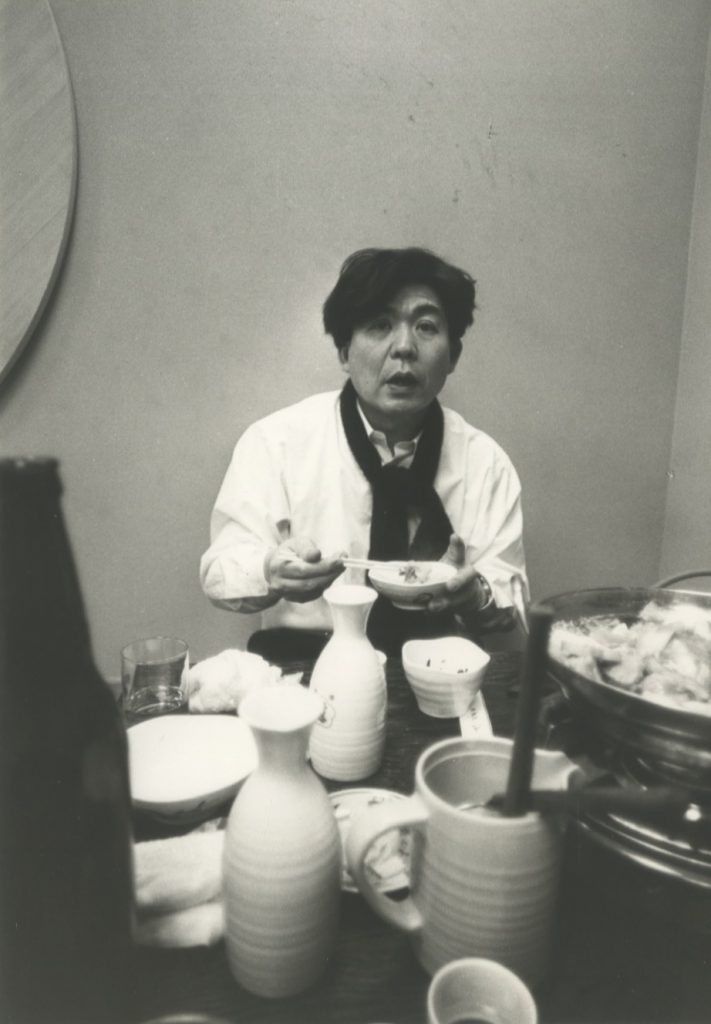

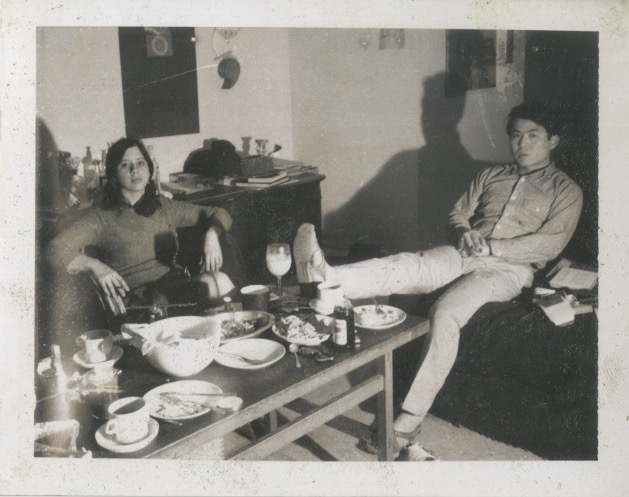

Later in his text, Ishiko describes illusionism as “the determined relationship in between humans and objects, approached from the side of human.”[10] If, as mentioned above, the act of seeing the film becomes the act of dissolving this relationship in between human and objects, the film’s focus was on the illusionism’s predetermined relationship in between human and objects. Consider the scene of the woman coming into physical contact with a table and a door (figs. 4, 5). Instead of using a table or a door normatively as an everyday tool, the woman focuses on a tactile exploration of the objects, investigating them with her hands and her body. Here, the woman approaches the table or the door not as a utilitarian tool with a pre-determined use, thus creating a commensurate relationship between the human and the objects. In the same vein, we may also reconsider the scene where the woman investigates the bicycle wheel prior to masturbating with it. Through such investigation, the woman and the bicycle wheel are able to blend with one another. A similar instance of human-object equivalence can also be found in the scene where the woman simultaneously massages her breast with one hand and a piece of fruit with the other (fig. 6).

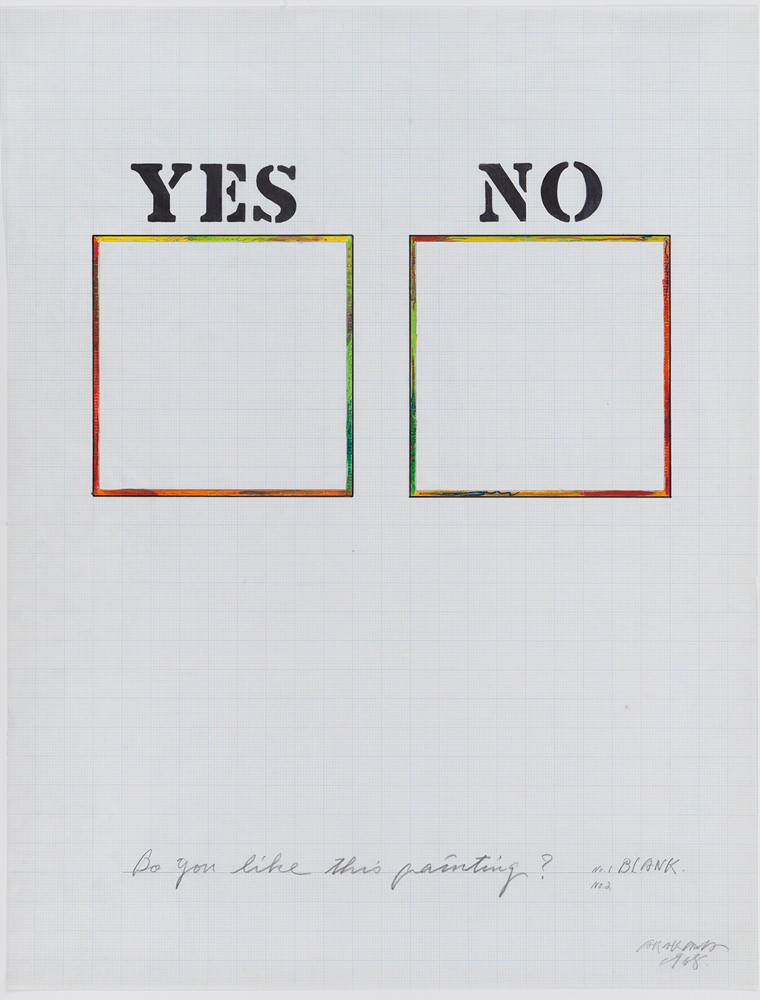

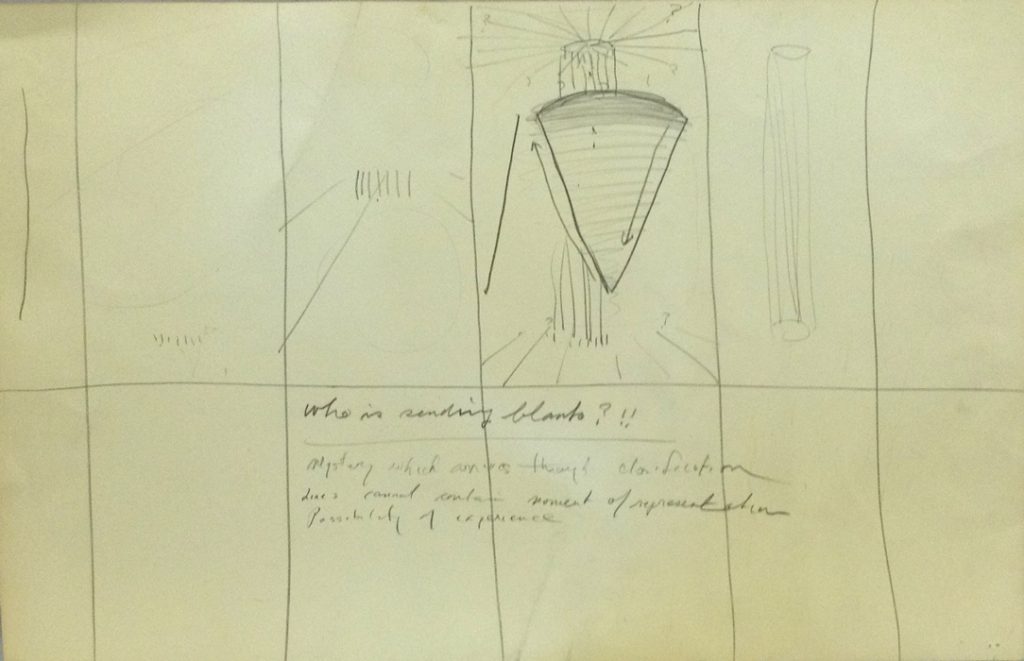

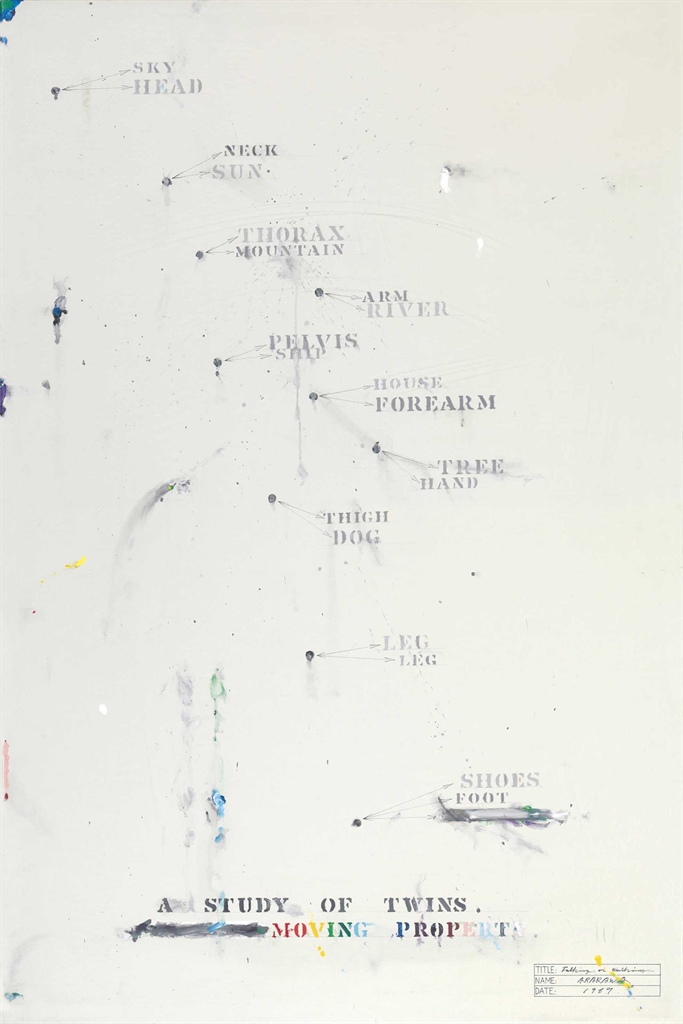

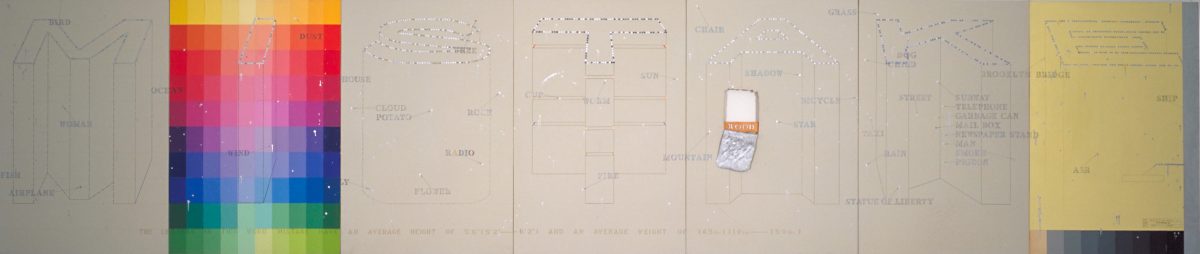

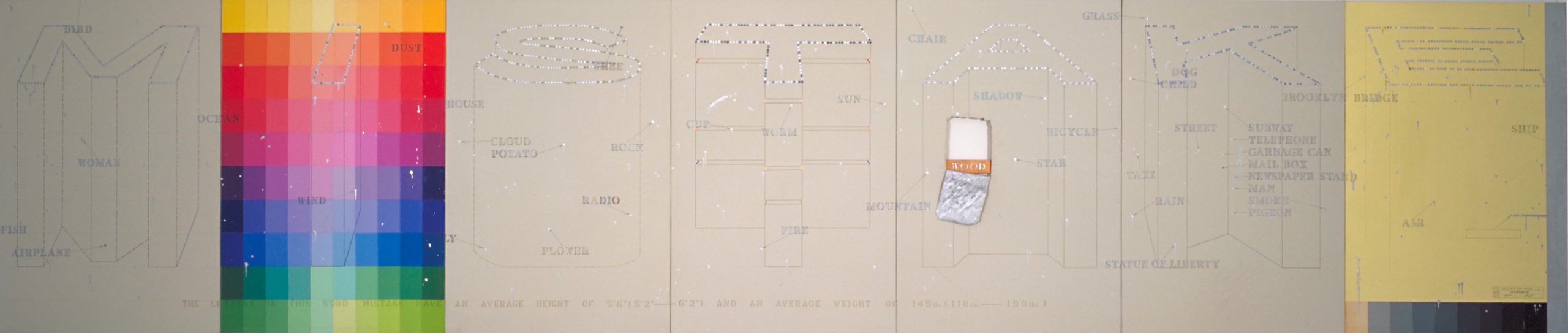

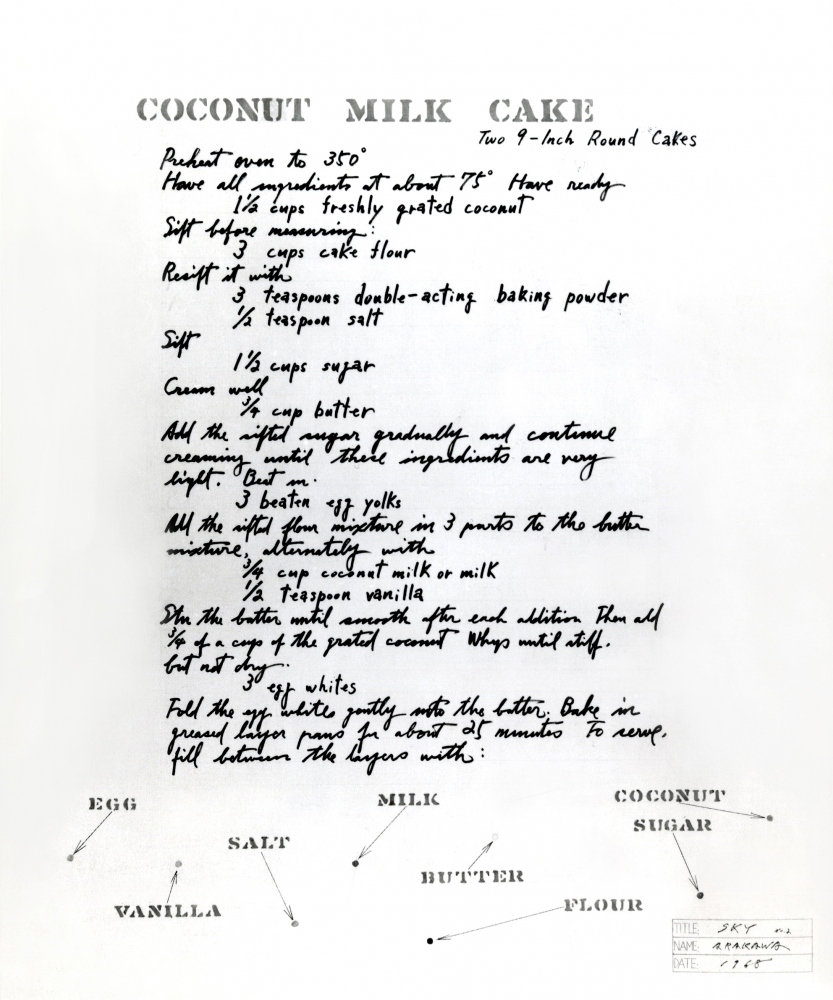

Based on this in-between human and object relationship in Why Not, Ishiko further contemplates on a series of Arakawa’s paintings from 1964–65 in which Arakawa stenciled objects that result in dim yet illuminating shadow-like forms on the canvas. By stenciling the form of an object rather than actually depicting it, Arakawa eschewed the tradition of illusionistic representation. Fully citing Arakawa’s words, Ishiko rephrases that these paintings reconsider illusionism in such a way that, “to think about the illusionism and perspective will be the clue to discover our analysis of memory and the disappearance of objects.”[11] For Ishiko, what these paintings reveal is illusionism’s predetermined relationship created in-between the object and human. Certain scenes in Why Not follow Ishiko’s reference on these paintings very closely, including the one in which the woman mimes drinking from a cup without a cup (fig. 7). Another appears roughly thirty-seven minutes into the film, when the woman is shown sitting on the toilet (fig. 8), while the voiceover states: “I saw a girl in a movie, sitting on a toilet seat eating a peach. She was looking into the bowl.” The narrator provides a detailed description of the relation between humans and objects, in the ways in which we might remember an image. In both scenes, we are made to be aware of how the relationship between humans and object are predetermined, and what Arakawa does in Why Not is to dissolve the relationship by the act of “seeing,” which could be singularly found in the space for filmic medium.

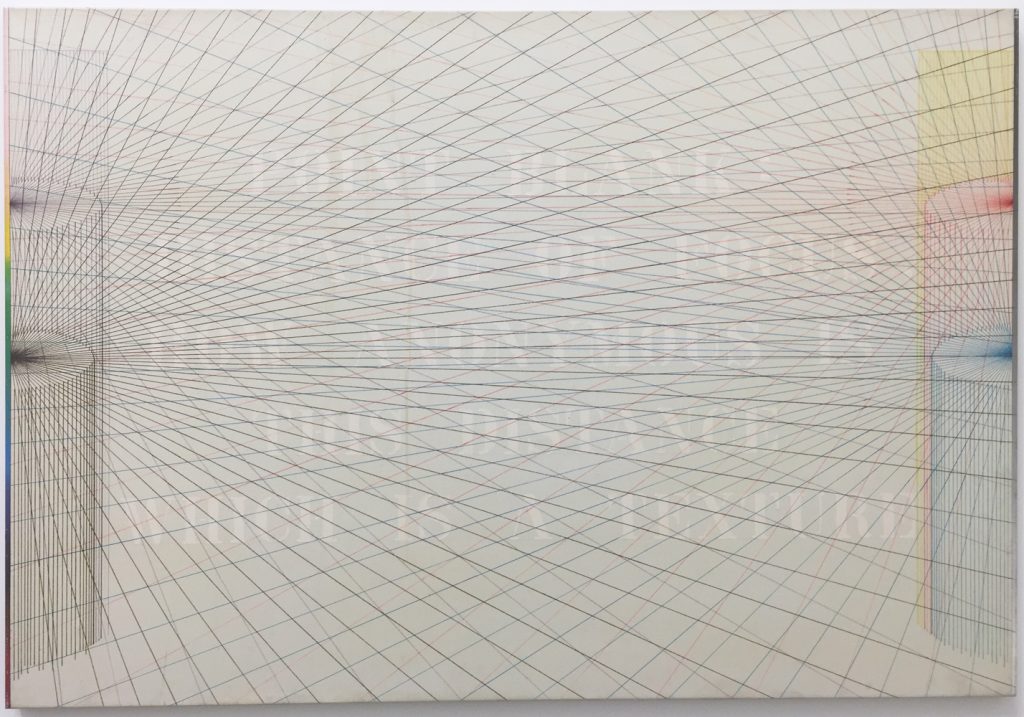

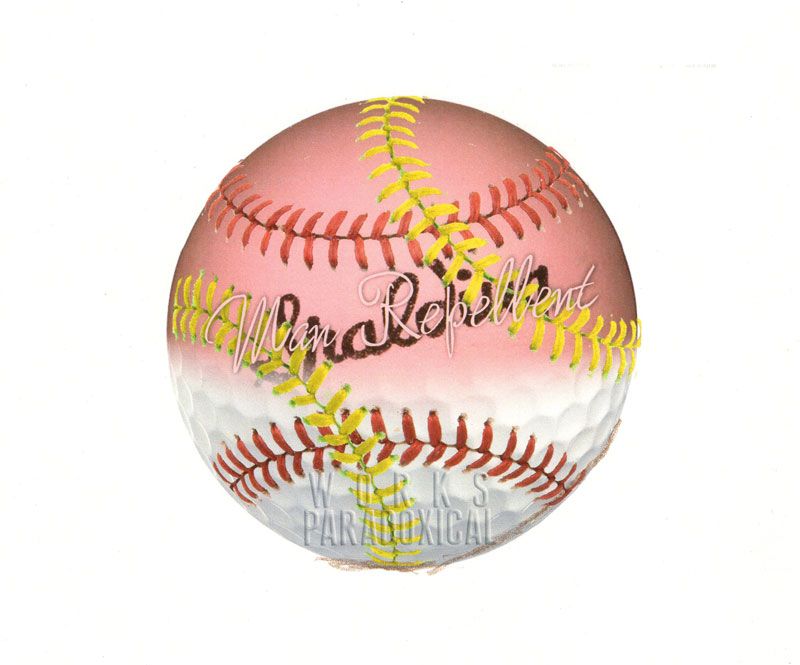

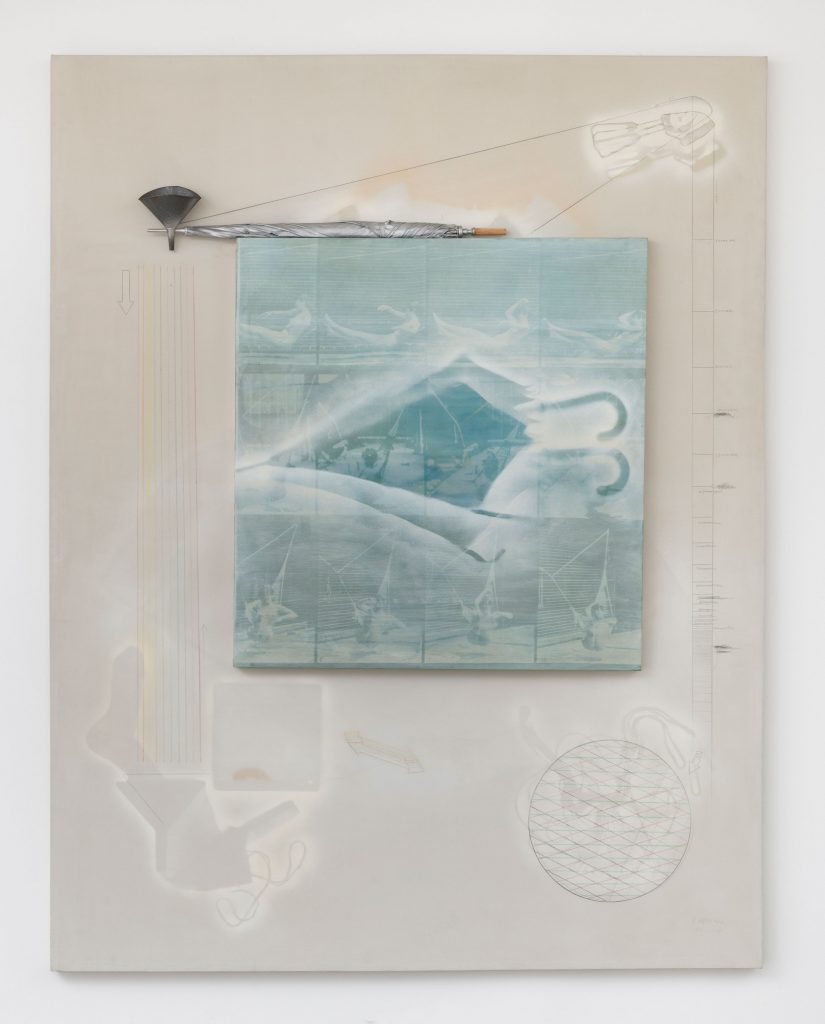

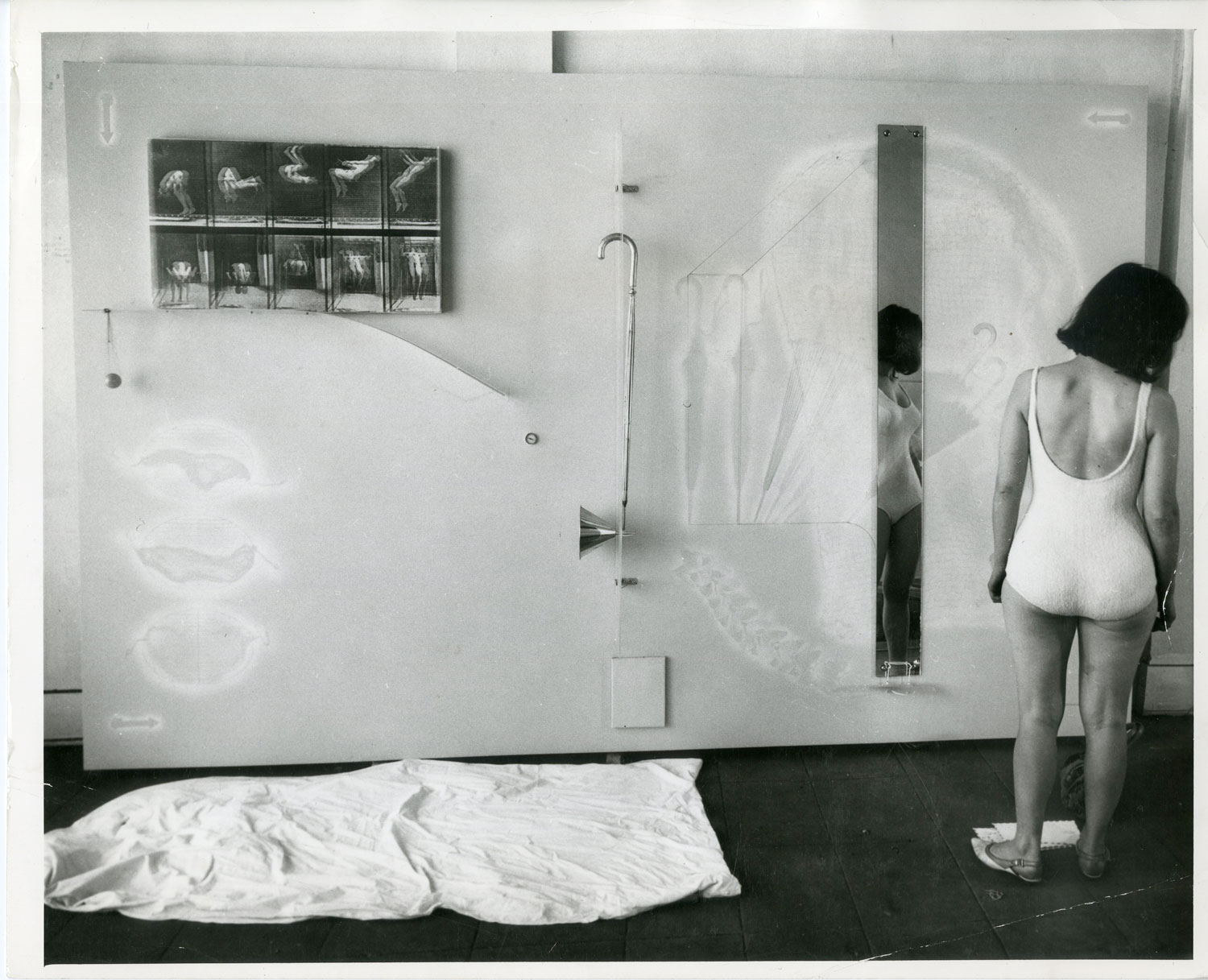

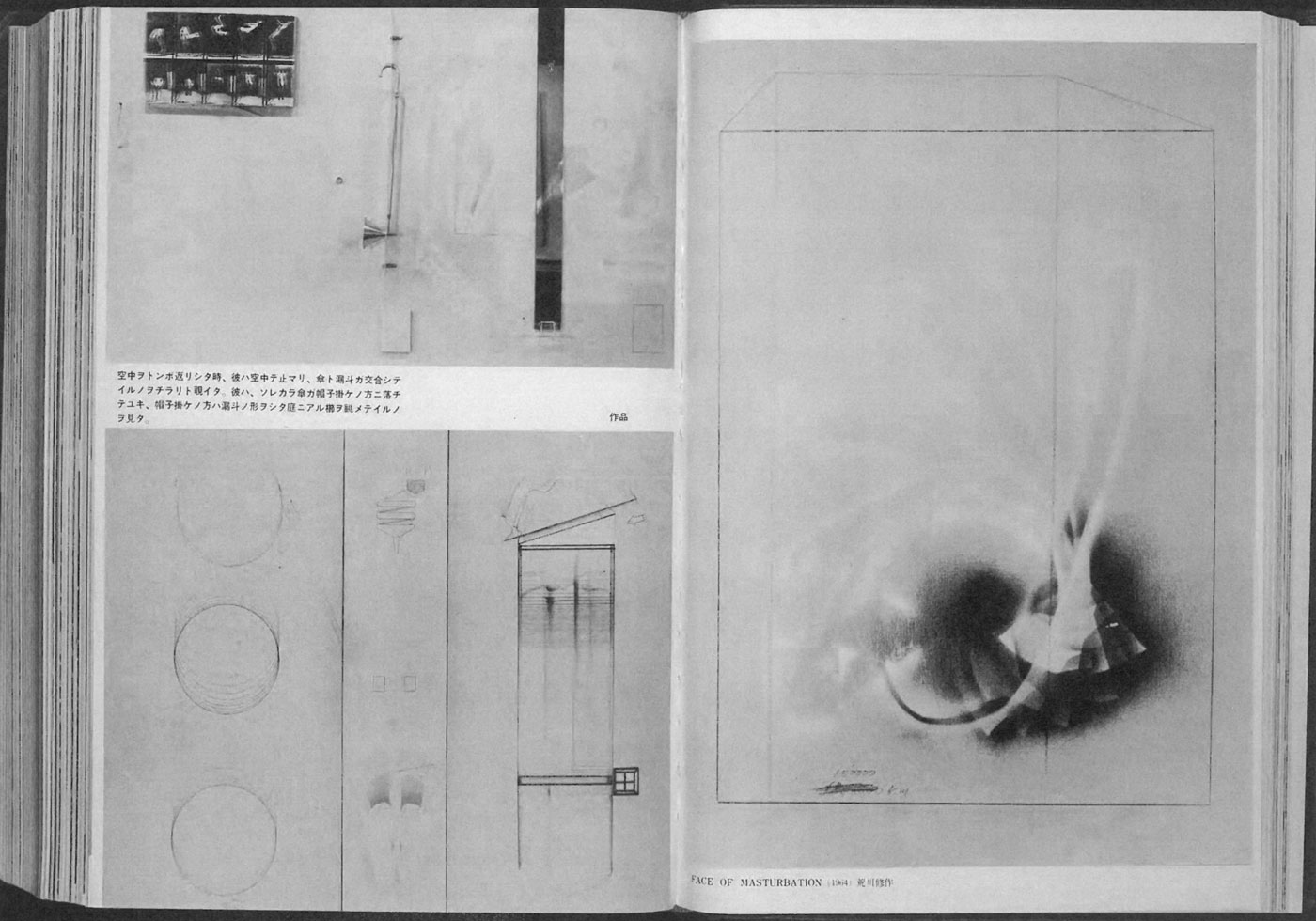

While further investigating Arakawa’s paintings from the mid-1960s, we find additional hints about his interest and experimentation with film, including loosely transferred images of Muybridge’s studies of motion alongside stenciled objects or sometimes objects themselves collaged on the paintings. In the center of ‘Untitled’ (1964-65; fig. 9) is a wooden board covered with an image-transfer of Muybridge’s studies of motion with a stenciled image of an umbrella layered over it. An actual umbrella penetrated by a funnel sits above this board. The relationship between the funnel, the umbrella, and Muybridge’s motion studies is perplexing, though Arakawa’s description of another painting, quoted by critic Yoshiaki Tono in 1965, provides a hint as to how it might be deciphered. According to Tono, Arakawa once described to him a painting by the name “The Umbrella and Funnel Having Intercourse,”[12] (fig. 10) which derived from the idea “to intersect things what a woman and a man could not ever intersect.”[13] These words imply that funnels and umbrellas symbolize sexual attributes and that ‘Untitled’ is an exploration of the relationship in-between the objects and their states of motion. Even in examples without Muybridge’s images, such as Face of Masturbation (1964; fig. 11), which captures the spinning motion of an indeterminable object, Arakawa demonstrates “motion” as a phenomenon that carries a meaning of sexual intercourse.[14] Given that movements are inherent to the filmic medium (“motion picture”), using a spinning bicycle wheel as a tool for masturbation in film shows Arakawa’s continued experimentation with “motion” as a representation of eroticism. In other words, Arakawa’s experimentation with objects and motion in his mid-1960s paintings becomes further emphasized in the elongated and concentrated masturbation scene in the filmic form of Why Not. In Film as a Subversive Art, Amos Vogel aptly noted the peculiar eroticism that arises in between the human and object in the film, which compels a reconsideration of the normative representation of eroticism as occurring between humans. As Vogel wrote, Why Not is steeped in a “cold, pervasive eroticism, which, oblique and displaced at first, finally becomes explicit in one of the most bizarre masturbation sequences ever filmed.”[15]

Junzo Ishiko’s writing testifies to the intricate ways in which Why Not demonstrates Arakawa’s interest in the human-object relationship and in the state of motion, all of which could be traced back to his paintings from 1964–65. Arakawa seems to have turned to film intending to address the issues of illusionism embedded in the relationship in-between human and object. As Arakawa’s placement of objects together with Muybridge’s motion studies in his paintings suggests, Arakawa thought the relationship in-between the human and object, which is predetermined in illusionism, could be dissolved by placing it into the situation of film. Arakawa’s foray into film, then, was inevitable: if, as Ishiko posited, Arakawa sought to “dissolve the ‘fiction (kyoko)’” through the “act of seeing,”[16] the film would have certainly seemed like the most suitable means for such experimentation.

And yet, it is still questionable what exact value Arakawa saw in the filmic medium of Why Not. In the very end of his unpublished manuscript “On Everything and Film: Why Not,” Arakawa reiterates:

At this moment in history which is a mistake what I make is viewed somehow as art. I live best by calling myself an artist. I fit in here now. Of course when things are better, society begins to make sense (or purposeful nonsense) I will fit anywhere and everyone will fit in art. Film is particularly good way to effect this. Why not try. Why not try everything.[17]

With the spinning bicycle wheel, death that is not an end, and dissolving relationships between the human and objects, the film swirls without a closure. Following Arakawa’s words, one could only guess that Arakawa’s swirling experiments in film were made in this spirit of: “Why not. Why not try everything.”[18]

[1] Duchamp had been a major influence on Arakawa since their encounter in 1962. By using the bicycle wheel as a masturbation tool, it is evident that Arakawa was trying to have dialogues with Duchamp’s sexual conceptions in his works, such as The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915/23.

[2] Before the screening at the Whitney, the film’s private screening was conducted at Virginia Dwan’s apartment in New York, on December 3, 1969.

[3] “Shoumen kara Sei ni torikunda Arakawa Shusaku no Hajimete no Eiga” (“Arakawa’s First Film that Confronts the Theme of Sex”), Bijutsu Techo, no. 322 (January 1970), 143. Why Not’s screening was first planned at the Film Art Festival in 1969, but it was canceled due to the organizer’s internal politics: some of the filmmakers accused the festival for becoming more of an establishment rather than maintaining the underground scene. In the same issue of Bijutsu Techo, Yasunao Tone wrote some of the details of this incident. See more in Yasunao Tone, “Uchinaru Geijutsu no Kachikiban Tadase” (“Revise the Value Base of Inner Art”), Bijutsu Techo, no. 322 (January 1970), 142-143.

[4] Takahiko Iimura, “Arakawa no Why Not ni tuite” (“On Arakawa’s Why Not”), Sogetsu Cinematheque, no. 69 (November 7, 1969), 4-5.

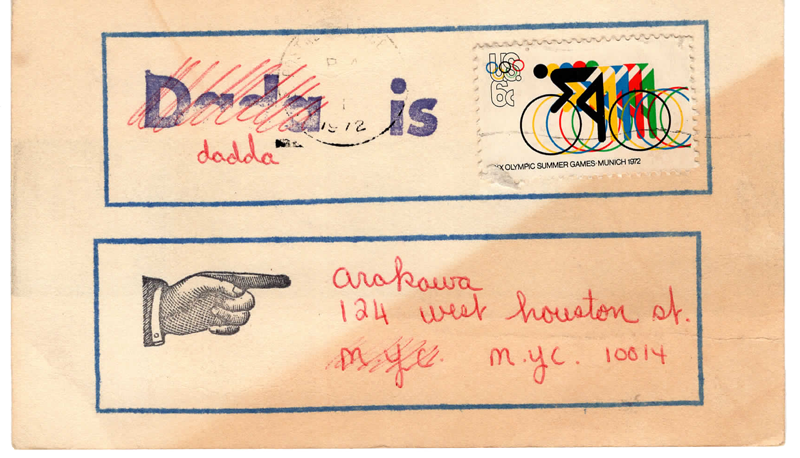

[5] Koichiro Ishizaki, “Dadaisuto no Dento–Arakawa Shusaku no Eiga Why Not” (“Dadaist’s Tradition–Shusaku Arakawa’s Film Why Not”), Eiga Hyoron 27 (January 1970), 50-52; Tasuto Oshima, “Eizou-Chitai ga Umareru Tokoro: Iimura Takahiko to Arakawa Shusaku no Sakuihin wo Mite” (“The Zone Where Moving Image is Born: On Seeing Takahiko Iimura and Shusaku Arakawa’s Work”), Space Design, no. 66 (April 1970), 104-105.

[6] Shusaku Arakawa, “On Everything and Film: Why Not,” unpublished manuscript, c. 1970, Box 2A03, Folder 9, Reversible Destiny Foundation Archives.

[7] In the manuscript, Arakawa wrote that twelve out of nineteen of the categories in The Mechanism of Meaning are explored in Why Not, including “Neutralization of Subjectivity,” “Localization and Transference,” “Presentation of Ambiguous Zones,” “The Energy of Meaning,” and “Degrees of Meaning,” among others.

[8] Shusaku Arakawa, “On Everything and Film: Why Not.”

[9] Junzo Ishiko, “Arakawa Shusaku no Eiga to Geijutsu-Zouhan: Ba ha Baitai de wa nai” (“Shusaku Arakawa’s Film and Art Rebellions: Space is Not a Medium”), Space Design, no.63 (January 1970), 105. All translations are mine.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid. Arakawa’s words originally appear in Yoshiaki Tono’s article “Arakawa Shusaku no Kinsaku” (“Recent Works by Shusaku Arakawa”), in Gendai Bijutsu 2 (February 1965), 8-19. Tono focuses on Arakawa’s paintings in the exhibition Arakawa: Dieagrams, held at the Dwan Gallery Los Angeles in March, 1964.

[12] The full title of this work is As he was somersaulting through the air, he stopped in mid-air and he caught a glimpse of the umbrella and the funnel having intercourse, he saw the umbrella falling down onto the hook which was looking at the comb in the funnel-shaped garden, (1964).

[13] Yoshiaki Tono, “Arakawa Shusaku no Kinsaku” (“Recent Works by Shusaku Arakawa”), Gendai Bijutsu 2 (February 1965), 19.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Amos Vogel, Film as a Subversive Art (New York: Random House, 1974), 28.

[16] Ishiko, “Arakawa Shusaku no Eiga to Geijutsu-Zouhan: Ba ha Baitai de ha nai” (“Shusaku Arakawa’s Film and Art Rebellions: Space is Not a Medium”), 105.

[17] Shusaku Arakawa, “On Everything and Film: Why Not.”

[18] ibid.